50 Years Later, the Apollo Program is Still Pure Poetry

If you are having a bad day, or you just want to feel better about being a human, I can offer the following unqualified advice: watch the opening eight and a half minutes—with the volume turned up—of Chasing the Moon, the new documentary about the space race that culminated in the Apollo 11 moon landing.

At the three-and-a-half-minute mark, you get the longest sequence I’ve ever seen of the Saturn V rocket soaring through the cobalt blue sky on July 15, 1969. It was moving at 2.76 kilometers a second, and would only get faster in later stages of the launch sequence.

I found myself with a lump in my throat as I gazed at that absurd machine—taller than the Statue of Liberty and powered by seven and a half million pounds of thrust at launch—heading toward the stratosphere. It was, as one commentator watching at the time brilliantly put it, “burning hot, straight, and true all the way,” and all the while with three astronauts sitting atop what was akin to a small atomic bomb.

There is something hugely powerful about that scene, something that taps into the timeless, Odysseus-esque nature of humanity: our unrelenting curiosity, our thirst for adventure; how we are always searching, always hoping for more, a better life, something beyond our feeble and frail bodies, perhaps even an afterlife. For me, all that was wrapped up in Saturn V’s blazing trail.

I should acknowledge, too, that, yes, I appreciate that there was a dark side to the endeavor. The space program appropriated billions of dollars sorely needed to tackle societal problems at the terrestrial level. It was exceedingly white; women and people of color were barely involved, and those who were were typically sidelined. The American space program was also the surrogate of the arms race of World War II, and recruited the skills of German scientists who had been caught up in the Nazi regime.

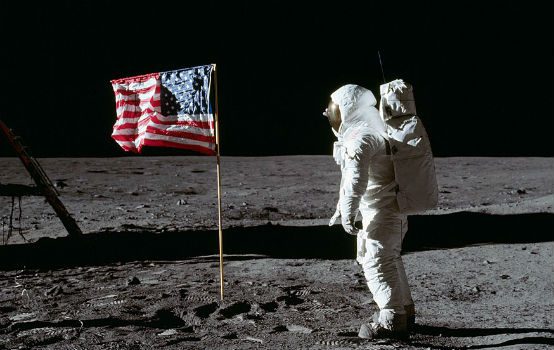

Yet at the same time, the space program, and particularly the Apollo 11 mission that inconceivably put a man on the moon, splendidly brought out those better angels of our nature, with lessons for today’s polarizing public space at ground level.

“I was thinking, ‘What a wonderful animal we are,’” Theo Kamecke, who at the time was filming a NASA-commissioned documentary film, said about what it was like to watch the Saturn V launch from Houston’s Mission Control. “That we could dream up this and get ourselves off the planet that we were born on and off to another world.”

He wasn’t the only one stirred. Much of the televised coverage got poetical, with those interviewed quoting Greek myth. The scale of the event seemed to engender in people an unguarded willingness to open up, rarely seen now among most commentators, so wary about how their quotes will be used. This was exemplified by Walter Cronkite, who had long followed the space program and couldn’t get enough of it. Cronkite anchored the CBS coverage of the moon landing with unabashed enthusiasm and bright-eyed wonder.

Even when Neil Armstrong fumbled his famous moonwalk line—“That’s one small step for man [when he should have said ‘…one small step for a man…’], one giant leap for mankind”—it still worked and resonates to this day.

The poetry was also in full flow during earlier stages of the space program, in the inspiring and hopeful speeches that President John F. Kennedy made in the early 1960s.

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people,” Kennedy told a large crowd gathered at Rice Stadium in Houston, Texas, on September 12, 1962.

During the Apollo 8 dry run for the moon landing, astronaut William Anders took the photo that became known as “Earthrise,” in which the swirling blue and white sphere is suspended alone amid the void of space. That photo is credited with helping inspire the environmental movement. Sixteen months after it was taken, Earth Day was created.

Anders and others who have ventured into space and seen the earth from that unique perspective have often remarked on what is sometimes called “the overview effect.” It’s typically explained as the gut realization that we are all in this together. That is certainly emphasized by those photos taken of Earth from space. Those pictures also capture the almost mythical quality of how our planet holds together in perfect union while all around it exists a gulf of nothingness, the bleakness of space ever pressing in but kept out by the protesting colors of life and creation contained within that most stark and unyielding circumference.

The Apollo 8 mission ran over Christmas, and the astronauts were instructed to broadcast a special Christmas Eve message to the masses. What on earth to say? After seeking advice, the three of them, Bill Anders, Jim Lovell, and Frank Borman, took it in turns to recite the first 10 poetical verses of the opening chapter of Genesis from the Bible. It was at the time the most watched television broadcast ever.

“I can’t speak for the other guys, but to me it was not a religious thing; [rather] it was a hard hit to the psychological solar plexus,” Anders later recalled.

World War I poet Wilfred Owen famously said that “the poetry is in the pity,” and there is great pity to be had in the Apollo space program, bringing with it nobility too. There’s a scene in the documentary that is just appalling to endure. It depicts the crew of the first Apollo mission sitting in the space module during a launch rehearsal. The footage then cuts to just a blank screen with audio from the astronauts as a fire breaks out in the capsule. They begin to shout for help. All three of them were killed, though they did not die instantaneously, as NASA claimed at the time. The wife of Ed White couldn’t bear the grief and eventually killed herself.

The tragedy of Apollo 1 brings home just how astonishingly risky and precarious the entire endeavor was, as well as how audacious. It was almost foolhardy, with a practically Heath Robinson approach to meshing together the available analogue technology to achieve something far more high-tech in concept.

That collective group of astronauts may have lacked diversity, but they exuded what Tom Wolfe famously called “the Right Stuff.” They were incredibly brave, displaying an almost preternatural calm and single-minded dedication in the face of pressures those of us on the ground can barely fathom.

Neil Armstrong, who also commanded the Apollo 11 mission, was a famously cool customer. Born in humble Wapakoneta, Ohio, a few years after the Ford Model T car had been discontinued, the legend that’s grown around him is full of accounts of his unflappable composure during his years as a naval aviator, a test pilot, and an astronaut.

It’s hard not to feel rather dejected comparing such Right Stuff with the character traits exhibited in society today, as we argue and tweet our petty recriminations. We would all do well with being reminded to look up at the moon and think beyond the silos and lifestyle enclaves we create for ourselves.

There was one bit of poetry related to Apollo 11 that we never got to hear. President Nixon had a contingency speech ready in case the mission failed and the astronauts never made it back. That address was to finish with an acknowledgment that, though the lost astronauts would be mourned, “every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.”

Whether his appropriation of Rupert Brooke’s “a foreign field that is for ever England” works doesn’t matter now, thankfully. More importantly, we can watch the Saturn V launch without a heavy heart, enjoying the ride.

Though that footage can also lead one to muse: if we managed to fire people off the surface of the earth to the moon in 1969, just think what we must be capable of doing today. It’s an inspiring and hopeful estimation, though it also raises the question: why aren’t we living up to our potential?

Have we gone far enough yet? Regardless, everyone has a right to feel some pride at being a member of this audacious, death-defying human tribe.

“We had gotten ourselves onto another world and put our foot there,” Kamecke said. “It was not just ‘We, the Americans,’ it was ‘We the humans, We the people of Earth.’”

James Jeffrey is a freelance journalist who splits his time between the Horn of Africa, the U.S., and the UK, and writes for various international media. Follow him on Twitter @jrfjeffrey.

Comments