Rumsfeld’s Ghost: Defense Reform in War and Peace

Strategic distractions derail structural reform at the Pentagon.

It has been said that the first casualty of war is truth, but a close second might be the reform of the American defense bureaucracy. While total war can overwhelm bureaucratic inertia through sheer scale and pressure, such crises are historical anomalies. Protracted limited wars, which have been recurrent since 1945, create the worst of both worlds. They consume the political capital and attention needed to drive reform and streamline innovation without creating the critical mass of crisis needed to overcome entrenched bureaucratic resistance. The inevitable inefficiencies and waste that arise during these conflicts in turn create more regulation. Expansive overseas contingencies consume strategic resources, privilege supplemental appropriations over base budgets, and create incentives inimical to bureaucratic reform. Strategic distractions derail the structural reforms needed to prepare for great power war.

In a recent speech to defense industry executives at the National War College in Washington, DC, Secretary of War Pete Hegseth employed a clever rhetorical device to underscore the enduring challenge of defense reform. His speech opened with a call to action against “an adversary that poses a serious threat to the security of the United States” and constitutes “one of the world’s last bastions of central planning”; an adversary that attempts to impose its will across continents and oceans and stifles free thought and crushes new ideas.

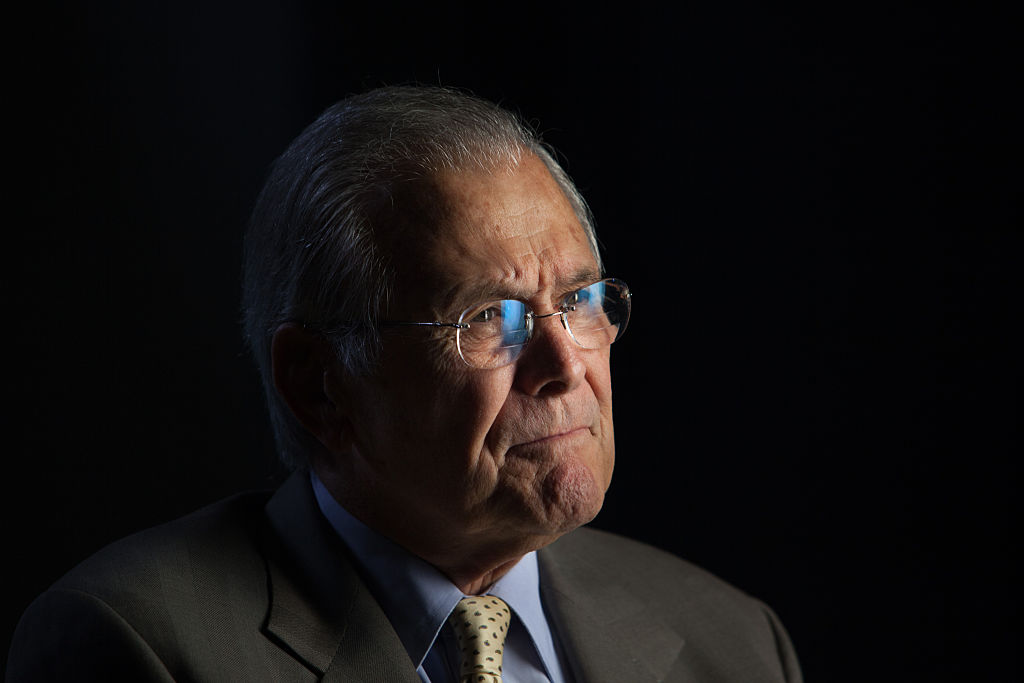

This adversary is not a foreign empire or rogue regime, but rather a domestic institution closer to home: the Pentagon bureaucracy. These words, however, were not his own, but rather an almost verbatim quote from a speech Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld delivered at the turn of the century. Their salience in 2025 is a testament to the enduring challenge of lasting reform.

Rumsfeld delivered his largely forgotten exhortation to reform the Department of Defense on Monday, September 10, 2001. The next morning, the Pentagon was aflame and his planned crusade against bureaucratic gridlock, institutional inertia, and ponderous procurement at home was eclipsed by planning for a crusade abroad. In the ensuing months, the emergent Global War on Terror absorbed the attention and engrossed the energies of the Department of Defense, shunting structural reform far from the forefront of defense priorities. Consumed by conflicts abroad, the secretary of defense lacked the political capital and focus to fight and win his war with the intractable “adversary” at home. The Rumsfeld revolution, though unlisted among the fallen, was among the casualties of the post-9/11 wars.

In August 2007, almost six years after his “Bureaucracy to Battlefield” speech, an article in Reuters declared the Rumsfeld reforms dead. “The much heralded "transformation" of the U.S. armed forces into a streamlined, computerized, unified fighting force is dead—or at least delayed—leading defense analysts said this week. Instead, the Pentagon is facing up to the much more urgent task of repairing and replacing traditional military hardware being ground down in Iraq and Afghanistan.” Indeed, the wars in the Greater Middle East had also ground down Rumsfeld, who resigned as secretary of defense in November 2006. His successor, Robert Gates, inherited a “grim situation” when he arrived at the Pentagon a week before Christmas and threw himself into containing the chaos the wars had unleashed, a task that would consume the lion’s share of his nearly five-year tenure as secretary of defense.

In the welter of war, most of the pre-9/11 defense reforms either stalled or were abandoned. In retirement, Rumsfeld defended his record as a reformer, arguing in a 2011 interview that the terrorist attacks had indeed been a catalyst for change. “Rumsfeld rattled off just a few of those sweeping changes made to posture the military for post-9/11 threats. Large Army divisions have been subdivided into more flexible and agile brigade combat teams. Special operations forces…have increased in numbers, authorities and equipment. U.S. forces have been ‘rebalanced’ around the world to better deal with 21st-century challenges and threats.”

In retrospect, however, these relatively modest reforms fell far short of the ambitious vision to transform the department Rumsfeld outlined in his September 2001 speech. Overall, the Pentagon bureaucracy of 2011 was as entrenched and intractable as it had been the day he returned to the E-Ring. There were of course notable tactical and operational achievements during the Global War on Terror, from JIEDDO's counter-IED efforts to the rapid fielding of MRAPs, but these tactical measures came at the expense of the strategic rationalization Rumsfeld envisioned in his speech.

For the ambitious reform agenda announced last week to succeed, the United States should avoid a protracted peripheral entanglement. Even a limited engagement in Latin America, Africa, or the Middle East could escalate and derail the momentum for reform. In May, Secretary Hegseth warned that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan could be imminent. To protect the measures that will strengthen our “shield of deterrence” and optimize the Department of War for great power competition, the administration must guard against a strategic distraction. Limited wars consume the political capital, resources, and focus needed to secure the reforms Secretary Hegseth demands and our troops deserve. The surgical strike against Iran and the recent campaign against narcoterrorists in the Caribbean have not spiraled into regional wars, but the risk of escalation persists. There is, however, instructive historical precedent for strategic restraint in the pursuit of defense transformation.

The most expansive modernization of the U.S. military, at least in the post-war era, unfolded from 1981-89, under the leadership of President Ronald Reagan. Though the defense bureaucracy expanded during his term, his administration maintained the pressure and attention needed to achieve generational modernization. Despite heightened tensions and numerous hostile regimes, Reagan avoided being drawn into a protracted regional war, enabling defense leaders to focus on modernization and reorganization. The Weinberger-Powell Doctrine, which set strict criteria governing the use of military force, ensured that the few foreign interventions which did occur (e.g. Lebanon, Grenada, Libya) were limited in scope and duration. The Reagan team achieved peace through strength by building strength in peace.

If the United States is drawn into a peripheral war, the reforms Secretary Hegseth announced last week could meet the same fate as the Rumsfeld agenda. While structural reorganizations like portfolio acquisition executives might survive if implemented swiftly, the cultural transformation within the Pentagon acquisition process could succumb to the short-termism that predominates during “short wars”. Another strategic distraction might revive or even strengthen “the old, failed process” Secretary Hegseth now aims to eliminate.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

“Speed to capability delivery” is essential to prepare the nation for strategic competition, but it is imperative that accelerated procurement prioritize the capabilities needed to deter and defeat our principal pacing threat. Our national security will be best served if the planned Wartime Production Unit expends its energies and resources procuring the weapons needed to win a great power war, not topple another rogue regime. Achieving the reforms announced last week requires sustained senior leader focus and leverage over prime contractors—both would dissipate in wartime.

At the close of his speech in 2001, Rumsfeld quipped, “Some may ask, defensively so, will this war on bureaucracy succeed where others have failed? To that I offer three replies. First is the acknowledgment, indeed this caution: Change is hard. It's hard for some to bear, and it's hard for all of us to achieve.” The hoped-for change would have been hard enough under ideal conditions. Under the unrelenting stress and strain of two wars, it proved insurmountable, even for a man of indomitable will, drive, and determination. Our leaders should heed the warnings of the Rumsfeld revolution that wasn’t lest today’s reform agenda become another cautionary tale.

From Vietnam to Afghanistan, extended combat operations divert focus from long-term organizational optimization to short-term operational needs. Strategic restraint in the coming years will preserve the senior leaders’ focus and the political capital these reforms need to transform how the department operates for a generation. The Pentagon bureaucracy is a resilient adversary that yields only under sustained pressure. Victory is best secured one war at a time.