The Daily Dreher

I want to give you readers who haven’t looked in on my Substack newsletter a heads-up. This is the last week I’ll be writing it for free. Starting next week, I’m moving to a paid model — five dollars per month, which amounts to 25 cents per day (I write it every weekday night). Now’s a chance to read back issues to see if this is something you’d like to have coming into your inbox every night.

You’ll find that this newsletter is written in a quieter, more pensive mode than this blog. I approach the newsletter as a kind of spiritual exercise in honing my inner eye to be more perceptive of hope, of beauty, and of the presence of God in our world. If you’re a reader of this blog, you know that I am pretty apocalyptic about the state of the world. I stand by that. But I am also a Christian husband and father who needs to be reminded why even though there is no reason to be optimistic, there is always reason to hope. The newsletter reflects my search for that. The kinds of things I write about there are too quiet for this blog, I think, and anyway, I am more direct about my Christian faith in the newsletter. As I’ve said before, I certainly don’t hide my Christianity, or the fact that I analyze the world from a Christian perspective, but I try hard not to come across here, in this secular magazine, as an advocate.

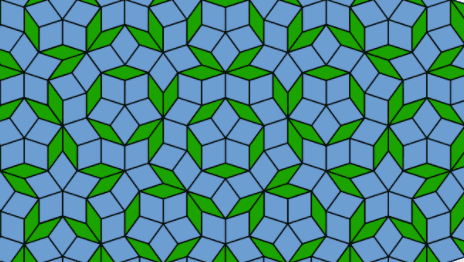

Here’s a link to today’s (well, last night’s) newsletter. Here we join a conversation about “Penrose tiling,” a phenomenon that the Nobel-winning physicist Sir Roger Penrose discovered when he was bored, and allowed his artistic instincts to kick in:

I didn’t know what Penrose tiling was until reading the Spectator piece, and looking up examples, but they sent me to my bookshelf, and to this passage from God And The World, one of the book-length interviews that Peter Seewald did with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who was to become Pope Benedict XVI. The cardinal said:

The Christian picture of the world is this, that the world in its details is the product of a long process of evolution but that at the most profound level it comes from the Logos. Thus it carries rationality within itself, and not just a mathematical rationality — no one can deny that the world is mathematically structured — not, that is to say, just an entirely neutral, objective rationality, but in the form of the Logos, also a moral rationality.

[Seewald:] But how can we know that with such certainty?

[Ratzinger:] Creation itself offers indications as to how it should be understood and upon what terms it should be accepted. This can be obvious even to non-Christians. But faith helps us recognize the clear truth that in the rationality of creation is to be found not only a mathematical but also a moral message.

Ratzinger goes on to discuss what C.S. Lewis identified in The Abolition of Man as the Tao, which he defined as “the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are.”

Ratzinger talks about how similar myths recur across cultures. Take the story of the Tower of Babel, which the future pope reads as a warning against attempting to usurp the Divine by humanity’s own efforts, and against trying to create a universal civilization by means of technology. It’s a story about the ruin that comes upon humankind when it tries to be God. Stories like this are common in the mythological treasury of mankind. They speak of a deep collective wisdom — of a Tao. This is not the same thing as relativism, but rather is testimony to a core moral order perceivable by men.

Last night I read this striking line from Marshall McLuhan, who was a practicing Catholic:

“Myth is anything seen at very high speeds; any process seen at a very high speed is a myth.”

Could we say, then, that myths are beautiful, in that they illustrate the moral order by representing a process at a very high speed? And is it not the case that one property of true beauty (as distinct from superficial beauty) is that it is capable not only of pleasing us aesthetically, but also giving us something to contemplate intellectually? And spiritually?

I have traced my spiritual awakening as an adult to an encounter with awe in the Chartres cathedral. I did not understand anything about that moment, other than that I had stumbled into the presence of God. To go back to a McLuhan passage I wrote about in last night’s newsletter, I was all percept; the concepts would come later. At some point within the past decade, I began reading books about the Chartres cathedral, and began to understand the staggering mathematical genius that went into its construction. None of it was accidental; all of it was precisely constructed to illustrate meaning. The entire medieval Christian cosmos was designed into the stone. I did not know what I was reacting to, and certainly could not have “read” the cathedral at age 17. What I perceived, though, was a dazzling symphony of order — layers and layers of harmonies, all of which pointed beyond themselves.

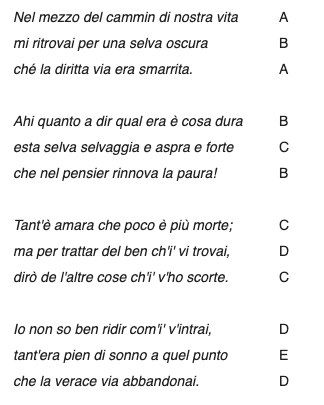

You can perceive this in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Unfortunately some of the beauty is lost in translation, like wearing sunglasses on a visit to the Uffizi. Dante constructed the entire tripartite poem — over 14,000 lines — in a rhyme scheme he devised for it: terza rima. Each Italian line consists of three lines of 33 syllables, interlocked links in a chain in this rhythmic pattern: ABA/BCB/CDC, and so on. Here are the opening lines from the Inferno, part one of the Commedia:

Dante ends cantos with either single lines or couplets, because it could go on forever like this without knotting the ends. The point is, Dante structures the poem geometrically in patterns of threes, to reveal the Trinitarian nature of reality. (Note: to reveal what is really there, not to impose a human concept on inert matter.) This is harder to see in translation, because it’s impossible to reproduce Dante’s terza rima faithfully in English. You see what I mean, though, about missing some of the beauty of the poem.

Thinking about Chartres, about Dante, and about Penrose tilings, brings to mind a quality of beauty identified by Elaine Scarry, in her wonderful little book On Beauty And Being Just. She writes that all beautiful things share an “impulse toward begetting.

It is impossible to conceive of a beautiful thing that does not have this attribute. The homely word “replication” has been used here because it reminds us that the benign impulse toward creation results not just in famous paintings but in everyday acts of staring; it also reminds us that the generative object continues, in some sense, to be present in the newly begotten object. It may be startling to speak of the Divine Comedy or the Mona Lisa as “a replication” since they are so unprecedented, but the word recalls the fact that something, or someone, gave rise to their creation and remains silently present in the newborn object.

For Dante, the generative impulse behind the Divine Comedy was his love of Beatrice and her beauty — but, as she tells him when they are reunited at the peak of the mountain of Purgatory, he erred grievously when he made an idol of her, instead of seeing her iconographically: as a medium through which the glory of God shone, and a sign pointing him to the divine origin of all beauty and love.

Sir Roger Penrose found that the design beauty of what would come to be known as Penrose tiling produced fruits in mathematical computation. For me, the beauty of Chartres generated religious conversion, and new life. Later, the beauty of the Divine Comedy served as map and a guide leading me out of a period of great despair. The beauty of my wife led me to marriage (23 years ago tomorrow), and has produced three children. And on and on.

What is so wonderful — literally, wonder-full — about the Divine Comedy is how Dante reveals that life is a pilgrimage towards greater revelation of light, of beauty, of harmonious order, and of love. All of these are the same thing in God. As Dante progresses through Paradiso, his ability to see depends on his growing in holiness. He is too weak spiritually to behold the full glory of God, shining through the heavenly beings; the divine light shining through their forms would annihilate him. Gradually, though, as his intellect, his nous, become illumined, he is able to perceive more truth, behold greater love, become more united to God, and filled with the Light.

There’s a reason I titled my book How Dante Can Save Your Life. I wasn’t kidding. And this is the spirit in which I’m trying to write this newsletter: moving forward towards sight, and light.

Read the whole thing. This is the kind of thing I’m writing over there. Starting this Friday, Jan. 1, I’m going to post the button that will allow folks to subscribe. I hope you’ll give it some thought. I never start writing that night’s newsletter until around 8pm or so, because I don’t want it to interfere with my TAC work. And I almost never know what I’m going to write about until I begin by assessing the day. I work really hard on it — you can imagine how difficult it is for the likes of Rod Dreher to look deep into the world for signs of hope — and find at times that I’ve spent four hours on a single issue. But like I said, this is important for me to do, as a spiritual exercise. I hope you get as much out of it as I do.