Two Ways The Church Can Die

In the current edition of the Mars Hill Audio Journal, Philip Turner, an Episcopal priest and former seminary professor, talks about re-centering Christian ethics. He’s on the show to talk about his latest book. In the interview, he talks about spending the decade from 1961 to 1971 in Africa, then returning to the US and having to take stock at what had happened in his country over that past decade.

He found an America that had radically changed. He tells host Ken Myers that it was plain to him that “Christian America” was passing away, and had passed away. That is, the idea that American culture (if not the American state) was centered around the message of the Church was now history.

(The secular Jewish sociologist and social critic Philip Rieff, incidentally, saw this in the mid-1960s, and said that religious leaders would desperately try to deny it, and work hard to stay “relevant” to the culture, but it would be too late. He was right.)

Turner says that back then, the Protestant Mainline still believed it had something important to say to America, and that America believed as well that the Protestant Mainline had something important to say to it. It wasn’t true. He said that when he returned to America from Africa, he saw that both conservative and liberal churches were desperately trying to assert that they weren’t in fact now on the margins of American life, and were trying to reclaim their prior social position. It was pointless, says Turner. Note well, he saw this in the 1970s.

Host Ken Myers says to Turner that today, we associate the “Christian America” concept with the Religious Right. Turner replies by saying that it was a common assumption in the past, and it’s still true of the Religious Left, though they wouldn’t admit it. He explains that liberal Christians may not use the same terminology, but they still believe have a vision for how they would like America to be, and are working to change it to conform to that vision. It doesn’t come in the #MAGA trappings that some of the more baroque disciples of the Religious Right adopt, but it’s still a fundamental belief that the Church can and should transform American culture.

I hadn’t thought about that before, but he’s right.

The problem is, says Turner, drawing on Stanley Hauerwas and John Howard Yoder, is that the churches in America today can’t transform America because they cannot even form faithful Christians within themselves. American Christians — and I would say this is almost as true of the Right as the Left — are far more assimilated to the norms and practices of American life than they are to building up their own common life as the Church, and themselves as faithful Christians whose first loyalty is to the Kingdom of God.

The medieval church, he says, had a vision of the church that we need to recover in this postmodern era.

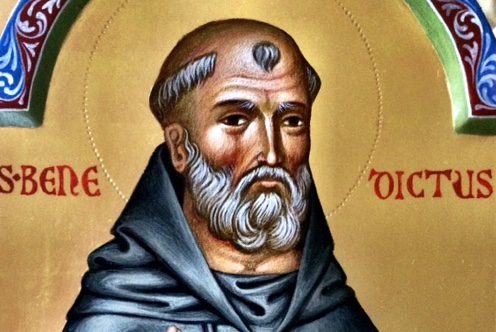

“My great example of someone who anticipated in a remarkable way the things we now need to learn is St. Benedict,” says Turner. “He knew that to be formed in Christ, you had to live in a community, over time, in which you subjected yourself to various practices and the dynamics of a community that you could not leave. He understood [that] the major function of the church is to become a community in which Christ is taking form. He had a lot of things to say about how that might happen.”

Turner goes on to say — this is a paraphrase — that the Church can only be what it is supposed to be for the world if it has its own inner life in order. And today, it manifestly does not.

Well. The Benedict Option did not come up in this conversation by name, though plainly, it did. I don’t want to dragoon Father Turner into the ranks of the Ben Op supporters, because I don’t know that he’s even heard about the book. But I appreciate his insights. My book takes the same position as Turner — a position also advocated by church historian Robert Louis Wilken, in this passage from his 2004 essay “The Church As Culture”:

Nothing is more needful today than the survival of Christian culture, because in recent generations this culture has become dangerously thin. At this moment in the Church’s history in this country (and in the West more generally) it is less urgent to convince the alternative culture in which we live of the truth of Christ than it is for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life, the culture of the city of God, the Christian republic. This is not going to happen without a rebirth of moral and spiritual discipline and a resolute effort on the part of Christians to comprehend and to defend the remnants of Christian culture. The unhappy fact is that the society in which we live is no longer neutral about Christianity.

I have quoted that passage a hundred times on this blog, and quote it in The Benedict Option, because its importance cannot be overstated. The Benedict Option is not about withdrawing into sealed enclaves. Rather, it is about getting our own inner lives — individually, in our families, in our churches, and in our communities — in an authentically Christian order. Only by doing that can we even begin to be the blessing to the world that God commands us to be.

I could be wrong in my diagnosis and prescription in the book, and if so, I can only benefit from honest criticism, which I welcome. Yet I am convinced that so many Christians — especially conservative ones — have mischaracterized The Benedict Option because it threatens them. If my diagnosis is right, then what they are doing in their lives and in their churches could well be wrong. They may be implicated in the decline and fall of American Christianity in ways they don’t want to face, because it means they will have to change their way of thinking and their way of acting in the world. Therefore, it’s easy to caricature it as a manifesto urging total cultural withdrawal, as a way to dismiss its analysis.

If you won’t listen to me, listen to Philip Turner, listen to Robert Louis Wilken. These older men have vastly more learning and experience in the world. They can read the signs of the times.

This is the way of the church’s death. Go this way, and we die:

Eugene Peterson on changing his mind on same-sex relationships and marriage https://t.co/a4SvzqHcmo my latest @RNS

— Jonathan Merritt (@JonathanMerritt) July 12, 2017

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

This is also the way of the church’s death. Go this way, and we die:

Ultimate selfie! Always an honor to visit with our great @POTUS! Forget #FakeNewsMedia. @realDonaldTrump is energized & determined to #MAGA! pic.twitter.com/I83b91Gv93

— Dr. Robert Jeffress (@robertjeffress) July 11, 2017

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

One way or another, the forces within American popular culture are pulling individual Christians and our churches in these directions, to their doom. Authentic Christians are an alien people in post-Christian America. The failure to perceive this, and to act on that perception, is going to be fatal. Giving ourselves over to these competing narratives of the Religious Left and the Religious Right, over the story of the Bible, is a dead end. Both represent two critical internal disorders in the life of the Church. Theologian Stanley Hauerwas has written:

In our attempt to control our society Christians in America have too readily accepted liberalism [here he means classical liberalism, shared by both Left and Right in the US] as a social strategy appropriate to the Christian story.

Liberalism, in its many forms and versions, presupposes that society can be organized without any narrative that is commonly held to be true. As a result it tempts us to believe that freedom and rationality are independent of narrative — that is, we are free to the extent that we have no story. liberalism is, therefore, particularly pernicious to the extent it prevents us from understanding how deeply we are captured by its account of existence.

The church does not exist to provide an ethos for democracy or any other form of social organization, but stands as a political alternative to every nation, witnessing to the kind of social life possible for those that have been formed by the story of Christ.

The church’s first task is to help us gain a critical perspective on those narratives that have captivated our vision and lives. By doing so, the church may well help provide a paradigm of social relations otherwise thought impossible.

And by the way, if you want to know how to live faithfully in post-Christian America, there is no better resource than Mars Hill Audio Journal. I cannot say this often enough, because I passionately believe it.

UPDATE: Please, some of you readers, stop being pedantic. I don’t believe that the Church universal can die. I am a Christian who believes Jesus’s promise that it will endure. But that’s not the same thing as saying that the church in a certain country will always live. Ask the Bishop of Hippo’s flock. The point simply is that a church will wither if it goes down either of these two directions. (There are many other ways for it to do so; this is not exclusive.)

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.