The Benedict Option Still Stands

I want to thank you readers who drop me letters, especially when you send me things to look at. You can’t possibly know this, but I’m inundated with e-mail daily right now, more than usual. It’s coming at a time when I am under a lot of pressure to finish the Benedict Option book, for an August 5 deadline. I’m also trying to move house (well, Julie is managing all of that, and doing all the heavy lifting, so to speak, but it’s still a major stressor). And trying to keep up with my blogging responsibilities during this intense political season.

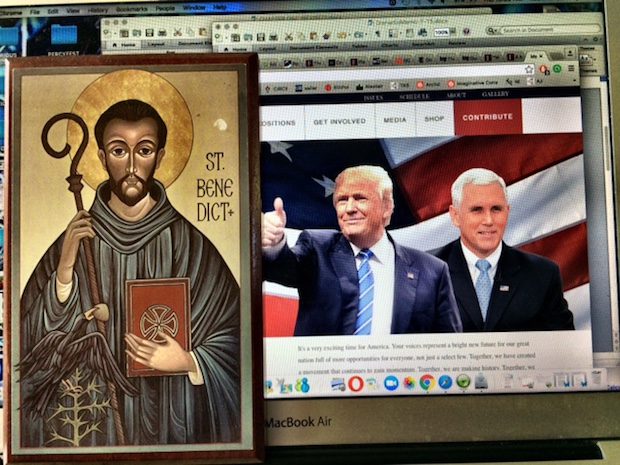

It’s also true that I am very, very distressed by the situation in our country. I believe that a Hillary Clinton presidency would be a catastrophe for the thing I care about most: religious liberty. Yet I believe a Trump presidency would be a different kind of catastrophe, one that would, among other things, make war more likely. (For example, even though I believe it was foolish to bring all those countries on Russia’s borders into NATO, I think it is foolish for Trump to put NATO’s security guarantees to them up for grabs. If Trump is sworn in, I foresee Putin sending tanks into the Baltics soon thereafter.) One of the core reasons that I am a conservative is fear of the mob. It’s why I loathe and despise what Black Lives Matter and other SJWs do on campuses, and this week, what Republicans aligned with Trump have been doing in Cleveland and beyond. American politics has entered a stage where the passions of the mob increasingly rule both sides, because emotional extremism is rewarded. I want no part of any of it.

I said earlier this year, when I reached an agreement with Sentinel, the conservative imprint of Penguin Random House, to write The Benedict Option, that I wouldn’t be speaking in much more detail about it on this blog. What you don’t see, by design, is how my thinking on the Ben Op has changed and deepened as a result of, well, deliberation, but also by interviewing so many people, and reading so many new things. Because of circumstances beyond my control — long story — I was not able to travel at all to report the book. I did go to Norcia, as you know, and I got to visit Clear Creek because they had a conference and paid my way to speak there. Otherwise, alas, I had to do this from home. I don’t think it will have made much difference in the end. I’ve got so much material I could easily have written a book twice as long as The Benedict Option is going to be.

So, to get to the point of this post: one of you readers sent me this morning this post from the Orthodox priest Father Stephen Freeman, reflecting on the Benedict Option. It delighted me because it reflects where my thinking has gone as I’ve been writing the book. I haven’t gotten into any of this on the blog these past few months, because I’m saving it for the book. Here are some excerpts:

Morality asks questions of right and wrong. What constitutes right action and why? Virtue asks an even deeper question. What kind of person is able to think and act in a right way? In terms of the gospel, we can see virtue as lying at the heart of Christ’s statement, “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” For someone who lacks virtue (is not “pure in heart”) even their reason and perception will be distorted. They will not only fail at doing the good, they will not even be able to see what the good is.

To suggest that we live in a culture in which virtue is absent is thus a very serious charge. It means that we are unable to agree on even the most mundane matters about what is right and wrong. Worse still, we have become the kind of people who are unable to even know the answer to such questions. MacIntyre’s next book, Whose Justice, Which Rationality, pushed his analysis even further. His work sits like a prophetic word over the modern landscape of moral discourse.

But After Virtue’s last paragraph remains. The Benedict Option has passed into current religious conversation, at least among those who think his analysis is correct. If virtue itself has collapsed, and our ability as a culture to understand and agree about the moral project has disappeared, how do we even begin to recover? Or, more poignant still, how do we even survive such a disaster?

The problem can be stated in terms of a circle. Virtue itself is a requirement for right action. How can people who lack virtue ever come to know what virtue itself is, much less go about creating a community of virtue? I’ve always thought of this under the guise of “take’s one to know one.” Obviously, something from outside is required in order for virtue to be nurtured.

More:

This, actually, is one way of understanding the gospel itself. If no one is pure in heart, then who can teach us about God? The answer is, Christ Himself. Christ is the one who is pure in heart. He Himself is the man of virtue. And so it is that Christ establishes the Church. Human beings do not actually live as individuals (despite all the modern rhetoric to the contrary). We belong to communities. If the communities to which we belong no longer know or are capable of virtue, then we ourselves cannot become virtuous.

The Church, however, is the living and abiding remembrance of virtue – the character of Christ Himself. The Church is the birth, in the world, of the living presence of the character of Christ. This is the heart of the “Benedict Option.” The monastic communities of Late Antiquity (the “Dark Ages”) were formed and shaped according to the character of Christ. “Character formation” was at the very heart of their life. In broader terms, we describe that formation as salvation itself.

It is worth noting, however, that these communities were not the result of people looking around and saying, “Gee, the Empire has fallen and the process of forming virtue has collapsed. Let’s start some monasteries and survive this thing.” The Benedict Option, in its original form, was God’s work, not man’s. This is necessarily the case.

This is absolutely the case. As I repeat in the book’s manuscript, Benedict did not leave the world for the sake of saving it. He left the world for the sake of saving his own soul. He knew that to put himself in a position where he was open to the Holy Spirit required living life in a certain way, in community. Hence the monastery. The monastic calling is a special one given to a relative few men and women, but the principle that believers need a community, a culture, and a way of life to keep themselves open to the formative (re-formative) power of divine grace is true for all of us.

It has always been true, but it is a truth we Christians in this chaotic time and place need to lay claim to urgently. This week, I interviewed Mark Gottlieb, a modern Orthodox rabbi (N.B., “modern Orthodox” Jews are Orthodox, but not like the haredim, the black hats), about what we Ben Op-oriented Christians can learn from the Jewish experience. One thing he said was that we Christians have to rediscover the power of regular daily prayer. He spoke of how participating with the community in morning, afternoon, and evening prayer, day in and day out, structures a believer’s entire reality. It does so by keeping one ever aware that we live and move and have our being in the presence of God. There is no substitute for praying like this. St. Benedict calls it opus Dei — the work of God.

Some folks like to say, “The Benedict Option sounds like nothing more than the Church being the Church.” To which I say, “Yes! Absolutely! But the Church — not just the institution, but you and me — hasn’t been the Church for a long, long time. And it shows.”

But “being the Church” requires taking on certain practices, and ceasing to do other practices. For most of us, it cannot be simply continuing to do what we’re doing now, and hoping for the best. To be clear, we aren’t Pelagians; we don’t believe that we can perfect ourselves. Any good thing that happens within ourselves is by the grace of God. But certain practices make us more open to that grace, and more resilient within that grace. And certain institutions make it more possible than others to live that grace-filled life in community. You’ll see what I mean more fully when the book comes out.

Father Stephen Freeman adds:

The true and ever-present Benedict Option remains whether anyone thinks about it as such or not. It is the long, slow, patient work of acquiring the virtues (theosis) by actually living the fullness of the Tradition as we have received it. It’s success is not for us to know or to foresee.

Go to Church. Say your prayers. Teach your children. Shop less. Share your stuff. Keep the commandments as we have received them. Pray for the grace to suffer well. Help those around you who are suffering. There is no need to wait for someone else to do it.

There is nothing more I can say to this than, “Amen and amen.”

Well, there is something more I can say to this, and I’m saying it in a book that, inshallah, will be published in February. I would appreciate your prayers as my editor and I are in the final round here. My health is not so hot.

Trump’s gonna Trump. Hillary’s gonna Hillary. We can’t stop any of that. What we can do is take the Benedict Option, because really, for faithful Christians, there is nothing else.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.