Christian Pessimism, Christian Realism

As I mentioned earlier this week, the religious liberty conference I attended recently was marked by sobriety in the face of the severe challenges the Christian community faces. Believe me, this is far more hopeful than the false optimism so many Christians cling to. One of the most common observations I heard from those gathered was that it is very difficult to shake one’s fellow Christians out of their pollyanna daze. They really do believe that somehow, God’s going to pull off a miracle that saves us all from suffering. Because they just cannot imagine that He would let that happen to us.

Barronelle Stutzman is not that kind of Christian. She is an absolute rock of faith, as well as one of the most gentle people I have ever met. You remember how I described the monks of Norcia as luminous in their serenity? That’s Barronelle, a 70-year-old Baptist from Washington state. She told me in an interview that Christians in America had better prepare themselves for the trials ahead.

“Whatever God has in store for us, He said be thankful for everything. Regardless of what happens, that’s what we need to do,” she said. “Christ gave his life for us. He put everything on the line for us. Are we not willing do that for Him?”

Those are just words on a page, but when you hear them coming out of the mouth of a woman who has suffered as much as she had, simply because she would not do flowers for a same-sex wedding, they are something far more powerful. She bears witness. She is not an optimist. But she is filled to bursting with hope.

I find that I crave talking to Christians with hope, but have no patience for those cockeyed with optimism, because it’s not based in reality. The philosopher James K.A. Smith dismissed the Benedict Option in an appearance this past March. From the transcript:

So the “Benedict Option” is a certain response of religious conservatives who are sort of, I would say waking up to the fact that American culture, generally is not going to form them in faith. Apparently this is a revelation. And therefore, and by the way, it seems so clearly catalyzed by the Supreme Court gay marriage decision, which to me is one of the reasons why I feel like it’s suspect.

I’m not deciding either way on that. I’m just saying that there is a, certain reactionariness about it that I find narrow and uninteresting. And so what they advocate is — it comes of course from the Benedictine tradition of monastic life. It really is an allusion to the final sentence of Alasdair MacIntyre’s famous work “After Virtue,” in which he says, “We are waiting now for another Benedict to come along and give us a society that actually forms virtue and character,” and so on and so forth.

And so the “Benedict Option,” as I understand it—I do think it’s misunderstood often—is about prioritizing an intentionality within Christian communities, in this case, to be much more intentional about formation and so on, and less confident that they will be able to steer, shape, and probably dominate wider cultural conversation — so it’s actually a refusal of the culture wars as well. What I just find a bit frustrating about it, is again, the particular reactionary point about marriage that I do think is the live option. It also comes off as alarmist and despairing in ways that I find completely unhelpful.

After the break, I’m going to give you a copy of the Fall 2013 issue of Comment magazine. I got to interview Charles Taylor a couple years ago, and one of the things that just struck me is that hope is his dominant posture. And I think that’s really important. I think if you actually have the long game in perspective here, if you have the long history in perspective — I spend most of my time reading St. Augustine in the 5th Century, and nothing surprises me, like nothing surprises me today, and so I don’t feel, like oh, “my goodness, the sky is falling because the Supreme Court decision,” or something like that. There’s a different set of expectations about that.

Finally, I would say what Rod is advocating as this new thing that we should be doing, just sounds like what the Church was always supposed to be doing. It comes off as a little bit like here’s the next great thing, and it turns out it’s only because we’ve failed to do what we were supposed to be doing. Again, Rod’s a friend, and what’s odd for me, is how much he sort of draws on my own work, to sort of articulate this, and yet, I, myself feel a certain distance from it because it comes with a grumpy alarmist despair that I don’t really want to be associated with.

Well, leaving aside the fact that I tell everybody I can that yes, the Benedict Option is simply the church doing what it ought to have been doing all along, but hasn’t been, I think that if James K.A. Smith, who appears to be reconciling himself to Obergefell, were to go talk to Christian lawyers and others who are more deeply involved in the fight for religious liberty, he would find his lack of alarmism impossible to sustain. It is well and good to point out that Augustine saw worse. But the people around the country that I talk to, and hear from almost every day, including Christian academics, may wonder why they are being counseled to calm down, because at least the Vandals and the Goths aren’t sacking our cities.

If you are an orthodox Christian and aren’t alarmed, you are not paying attention. That alarm should not paralyze you with fear, but it should tell you that it’s time to take action, to prepare yourself, your family, and your community spiritually and otherwise, for the trials ahead.

Michael Brendan Dougherty writes about Mary Eberstadt’s latest:

In her new book, It’s Dangerous to Believe: Religious Freedom and Its Enemies, Mary Eberstadt finds a dark pessimism settling over many American Christians when they contemplate the future. They perceive a foreboding shift in public attitude. Once there seemed to be a broad and liberal respect for the free exercise of religion, even in public life. But now, the very cultural forces promoting tolerance and diversity treat Christians and their institutions with broad suspicion, and demand absolute conformity with an egalitarian ethos that has only recently even announced its own existence.

Believers see the recent battles over religious liberty in the courts and in public opinion as a desire to purge orthodox Christian views, particularly about sex and the two sexes, from the public-facing institutions that they have built: their schools, hospitals, and adoption agencies. Instead of their First Amendment right to free exercise of religion, Christians are being offered, with a great deal of bitterness, mere “freedom of worship,” narrowly defined to thinking your own thoughts in your head and participating in ceremonies behind closed doors.

Eberstadt documents in exhaustive detail this widespread social urge to rob Christians of their livelihoods and their good names, merely for believing what their churches have always taught, and acting on those beliefs. This is not just a handful of bakers who refused to make gay wedding cakes.

Dougherty is darker than Eberstadt:

Eberstadt argues that the way to end the moral panic about Christians and their institutions is for the two camps in the culture wars to acknowledge their differences and then agree to disagree.

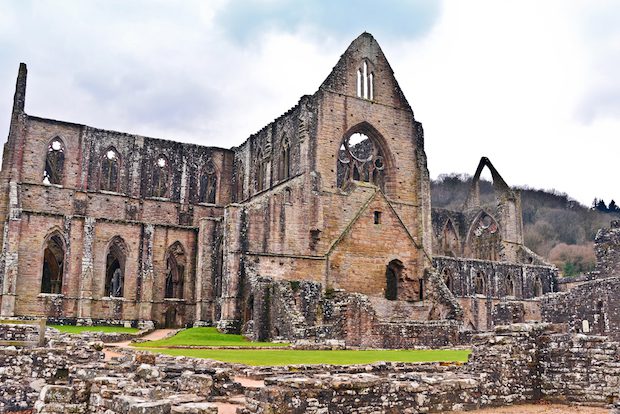

But I can’t help but wonder if the analogy that is more appropriate to our times is to the English Reformation. There, a new rising faith, led by Henry VIII and his daughter Queen Elizabeth I, confronted an institutionally powerful set of church institutes. There were many elements of moral panic around this conflict, particularly the fear of subversive Jesuits sent from the Continent to destroy England’s state power and ruin the morals of her people.

But this wasn’t a moral panic that just subsided. The new faith was part of a state-building and state-reforming project, and that meant the continued prosecution of the old one for centuries. Instituting the new faith meant crushing those institutions, robbing them of their wealth, and taking over their social functions for the new faith. Driving the old faith underground made Catholics lest trustful of the state, and in turn obedient citizens became more distrusting of them. English anti-Catholicism meant the banning of Catholics from many vocations, especially those in public life.

Read the whole thing. I bought Eberstadt’s book yesterday, so I’m going to read it and make up my own mind. David P. Goldman, in a friendly but critical review in First Things, says similarly that Eberstadt is too optimistic. Eberstadt, he says, calls what the left is doing to traditional believers a “witch hunt,” which understates and mischaracterizes matters:

By contrast, the purge of traditional Christians and Jews is a heretic hunt, an Inquisition, whose objective is to isolate and punish individuals who actually profess opinions contrary to the prevailing orthodoxy. There can be some overlap between an Inquisition and a witch-hunt, to be sure. But today’s liberal Inquisitors are not searching for individuals secretly in communion with God—yet.

This is a critical distinction. Witch-hunters eventually discover that burning a few old hags does not prevent cows’ milk from souring. Inquisitions, by contrast, usually succeed: The Catholic Church succeeded in stamping out broadly held heresies, as in the Albigensian Crusade of 1220-1229, which destroyed between 200,000 and 1,000,000 inhabitants of Cathar-controlled towns in Southern France. In many cases a town’s entire population was killed, just to make sure. For its part, the Spanish Inquisition eliminated all the Jews, Muslims, and Protestants, although it sometimes drove heretical opinions underground, with baleful consequences for the Catholic faith.

Because Eberstadt confuses the present persecution with mere witch-hunting, she hopes that the witch-hunters will realize their error and do the decent thing.

They’re not gonna, says Goldman (an Orthodox Jew and a friend of mine, I should say), because they perceive traditionalists as a threat to the social order. This is not going to end anytime soon. Goldman says that the only alternative is for Christians to counterattack. They have nothing to lose that won’t be taken from them anyway, so they might as well fight.

He also says that the Benedict Option is “impractical,” because, as he explains in the comments, he thinks it’s about going Hasidic. Um, no. If I had to live with Christian Hasidim, I would be the world’s worst at it. I’ll make sure my friend gets a copy of the galleys when they’re out. He’ll see that I’m up to something broader and more ambitious. Frankly, there is nothing un-Ben-Op about counterattacking. But unless we are committed to the Masada Option, we had better be busy with long-term plans for resistance.

Overreacting and falling into paranoia and loathing is a temptation. But so is assuming everything’s going to be okay in the end, and believing that you can avoid trouble by being nice. Sooner or later, you are going to have to take a stand — and if you stand on Christian orthodoxy, you are going to be knocked flat. Can you take that? You had better be able to. They’re coming for the pharmacists and florists and cake-bakers now, but if you think they’re going to stop at the fringes, you are out of your mind. If you’re a teacher in the Fort Worth public schools, and you refuse to teach gender ideology to your elementary school students, you will be fired under the new policy there. In Texas.

Hope is the sure conviction that suffering has meaning in God’s inscrutable will, and that it can be redemptive. That’s not optimism. Be hopeful, but not optimistic. It’s later than you think.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.