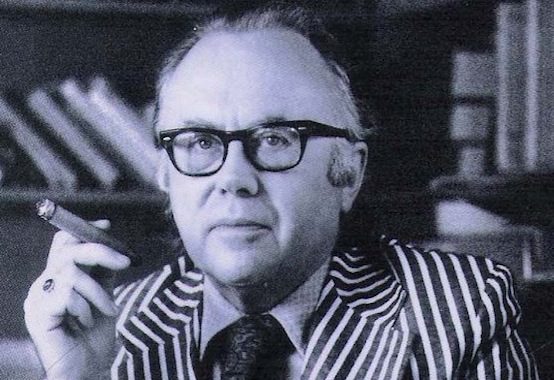

Russell Kirk at 100

Even among the odd, Russell Amos Kirk was unusual. Perhaps only in America could such an eccentric and anti-individualist individual have arisen. And arise he did.

One hundred years ago, Kirk entered the world. Born to poverty-stricken but bookish Anglo-Saxon Celts on the wrong side of the tracks in Plymouth, Michigan, probably very few looked at his young parents and believed them capable of producing a genius. Kirk’s mother was a quiet saint, but his father was a ne’er-do-well who never quite got his life together and certainly never earned any respect from his only son. Like so many who settled in Michigan during the 19th century, the Kirks and their relatives had come with the first waves of immigration to the northern American colonies, slowly migrating across New England, upstate New York, and towards the Great Lakes. They had lost their Puritanism at some point, these old Yankees, and were to become the supporters of Abraham Lincoln and the proud backbone of the Union army during the American Civil War. Northern and agrarian, they replaced their lost Knoxian faith with not only cherished books but also with séances, faith healings, levitations, and bizarre spiritual liturgies.

Like so many traditionalists of the 20th century, Russell Amos Kirk (“Jr.”) revered his grandfather while dismissing his father. His traditionalist sympathies and piety were lacking in the previous generation, who deemed it unworthy even of consideration. All real hope rested in his grandfather’s cohort. Russell especially admired his maternal grandfather, Frank Pierce, a well-read and rough Stoic character.

Unsure of what greater things to believe, young Kirk found certainty in his mother and in her father. Through their influence, he read everything he could find, from the collected works of James Fenimore Cooper to Thomas Jefferson to Karl Marx, all while still in his tweens. He never stopped reading, and possessed amazing recall courtesy of what was almost certainly a photographic memory. Of all the great things in the world, however, nothing bested a walk with his quietly certain grandfather. On those walks, Russell felt his mind sharpen, his soul enlarge, and his world come into focus.

Not realizing how abnormal it was for a 12-year-old to read and devour all the knowledge and wisdom around him, Kirk never felt the sting of poverty, so immersed was he in the life of the mind.

When moved, he began to write, and once he started to write, he never stopped. One of his most loyal students, Wes McDonald (RIP), noted that Kirk probably wrote more in his lifetime than what even the most educated American reads in a lifetime. Having been privileged to read all of Kirk’s published books, articles, and reviews, as well as his private correspondence and papers, I can affirm McDonald’s suspicion. Everywhere Kirk traveled, he took with him his three-piece tweed suit, a swordstick, and a typewriter. The eminent scholar Paul Gottfried claimed that watching Kirk at the typewriter was akin to watching Beethoven compose. According to those who knew Kirk well, he could type while carrying on a conversation simultaneously. His photographic memory allowed him to reference things he had read over the years without looking them up. Sometimes in a furious day, he might answer tens or even hundreds of letters, and often in a furious night, he could produce a full-book chapter.

Almost as soon as Kirk entered Michigan State College as an undergraduate in 1936, Professor John Abbott Clark took him under his care and introduced him not just to the profoundly important but already neglected works of Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More, but to Socratic and Ciceronian humanism as a fundamental part of the Western tradition. During his college years, Kirk combined his love of romantic literature, the humanist ideals of Babbitt and More, and the stoic wisdom of his grandfather into what would be recognized by 1953 as modern conservatism. While earning an M.A. in history at Duke in 1940 and 1941, Kirk also discovered an intense love of Edmund Burke, whom he’d encountered through Babbitt and More in college but only indirectly. It was while writing his M.A. thesis on the rabid Southern republican John Randolph of Roanoke that Kirk first felt the influence of the greatest of the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesmen. Though many scholars—from Daniel Boorstin to Leo Strauss to Peter Stanlis—were also re-discovering Burke (along with Alexis de Tocqueville) in the 1940s, it was Kirk’s 1953 work, The Conservative Mind, that would once again make Burke a household name in America and, to a lesser extent, in Great Britain.

By the time America entered World War II, a very young Kirk—rather enthusiastically Nockian and anarchistic—already despised Franklin Roosevelt for his mistreatment of ethnic and religious minorities at home and abroad and his militarization of the American economy. As much as Kirk hated Hitler, he did not see FDR as a viable alternative. Succumbing to the draft in the late summer of 1942, Russell Amos Kirk, B.A., M.A., endured in the military the only way he knew how: by spending all of his free time reading. Before shipping off to training at Camp Custer in Michigan (he would spend much of the war as a company clerk in the desert wastes of Utah), Kirk purchased every work of Plato and the Stoics that he could find. From his childhood to his death, he kept a copy of Aurelius’s Meditations close to him. As in the rest of his life, it would serve as his greatest comfort during the war. As he wrote in a personal letter, “everything in Christianity is Stoic”:

Really, the highest compliment I can pay to the Greeks is that they could understand and admire the Stoics and admit their own inferiority. Were the Stoics to ask the moderns the rhetorical questions they asked the Greeks, the moderns also would accept the questions as rhetorical—but would answer them in exactly the opposite manner.

In imitation of Aurelius, his own war diaries attempted to describe the world around him through the lens of the Greek and Roman-adopted Logos, the eternal order of the universe. “’Nothing is good but virtue’—Zeno” Kirk scrawled across the cover of his first diary.

That same Stoicism, however, also made Kirk profoundly aware of the majesty of nature, even in the desert wastes of the Great Basin. Though he had always been an excellent writer, something fundamentally changed in his view of the world in September of 1942. Kirk, though only 24 when he wrote these words, is worth quoting at length:

This is written in the dead of night (and why shouldn’t it be the dead of night? All else is dead here, and has been ever since the beginning of time). …I handle special orders, travel orders, daily bulletins, and the like—a great many stencils to type—and am a star contributor to the Sand Blast, our paper, a copy of which I’ll send you once we get the next issue out; I intend to do some brief literary criticism for it, once the post library opens. Officers are affable, hours required are briefer than those I had as a civilian, and the work is very light and sometimes infrequent. …I’ve grown to endure the country in true Stoic fashion, and take a certain pleasure in feeling that I’m a tough inhabitant of one of the most blasted spots on the continent. There’s enough leisure here, and that’s a lot; the winters are said to be dreadful, but I have found fears exceed realities here, as everywhere. Already we have very cold mornings and evenings, and as I write a great sand-laden wind very chilly, is howling around the shacks of Dugway. Coming here tends to make me lean toward the Stoic belief in a special providence—or, perhaps, more toward the belief of Schopenhauer that we are punished for our sins, in proportion to our sins, here on earth; for I’d been talking of Stoicism for two or three months before I burst into Dugway and there never was a better and sterner test of a philosophy, within my little realm of personal experience—to be hurled from the pleasures of the mind and the flesh, prosperity and friends and ease, to so utterly desolate a plain, closed in by mountains like a yard within a spiked fence, with everywhere the suggestion of death and futility and eternal emptiness. But, others, without any philosophy, live well enough here; and, as Marcus Aurelius observes, if some who think the pleasures of the world good still do not fear death, why should we?

Though disgusted by the ill treatment of Japanese Americans and the dropping of the atomic bombs, Kirk remained loyal to, if not uncritical of, the United States. The Army finally released Kirk in 1946, and after two years of teaching Western civilization at Michigan State, he accepted a position in the doctorate program at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland in 1948. It was after a messy breakup with a girlfriend in the fall of that year that a dispirited Kirk devoted himself to “an invigoration of conservative principles.” The five years of research and writing following that breakup would become The Conservative Mind, which was published in the spring of 1953.

Amidst today’s whirligig of populist conservatism, crass conservatism, and consumerist conservatism, we conservatives and libertarians have almost completely forgotten our roots. Those roots can be found in Kirk’s thought, an eccentric but effective and potent mixture of Stoicism, Burkeanism, anarchism, romanticism, and humanism. It is also important—critically so—to remember that Kirk’s vision of conservatism was never primarily a political one. Politics should play a role in the lives of Americans, but a role limited to its own sphere that stays out of rival areas of life. Family, business, education, and religion should each remain sovereign, devoid of politics and politicization. Kirk wanted a conservatism of imagination, of liberal education, and of human dignity. Vitally, he wanted a conservatism that found all persons—regardless of their accidents of birth—as individual manifestations of the eternal and universal Logos.

A hundred years after the birth of Russell Amos Kirk, those are ideas well worth remembering.

Bradley J. Birzer is the scholar-in-residence at TAC. He holds the Russell Amos Kirk chair in history at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.

Comments