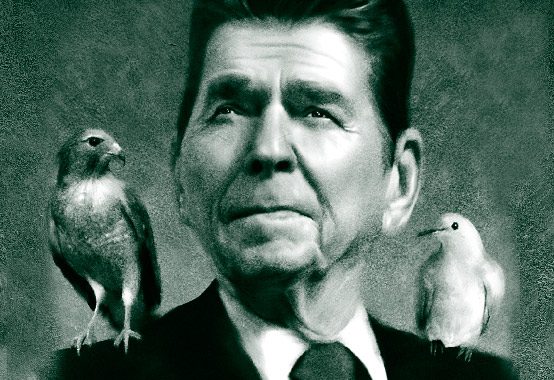

Reagan, Hawk or Dove?

The uses and abuses of Ronald Reagan’s record have greatly influenced arguments on foreign policy over the last 25 years. Reagan’s example has been cited to support everything from engagement with Iran and withdrawal from Iraq to George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda” and the arming of rebels in Libya and Syria. His name has also been abused to justify an aggressive, militarized post-Cold War role for the U.S. that has little to do with the foreign policy that Reagan conducted while in office. Perhaps the most useful thing conservatives can learn from Reagan today is that his example is of limited relevance in a world where the Soviet Union no longer exists, Communism has collapsed almost everywhere, and the U.S. is more secure than it has been in decades.

The farther removed from Reagan’s time in office that conservatives are, the more intent vying factions on the right have become to identify their preferred foreign policy with him. Reagan is the one national Republican figure of the last 40 years whose reputation with most conservatives has improved over time. That is partly the result of Reagan’s departure from the political scene after leaving office, and it is also partly because of the tendency of later conservatives to reimagine his administration as what they wished it had been. As the last politically successful, self-identified conservative president, Reagan is one of the few modern leaders most on the right will agree to imitate. Anyone wanting to make his policy arguments appealing to conservatives feels the need to identify them with the Reagan record.

Self-described realists often emphasize Reagan’s willingness to engage the USSR in arms-reduction negotiations. Noninterventionists tend to focus on his aversion to sending U.S. forces abroad and his relatively rare and limited uses of force. Hawks in general remember Reagan for his increased military spending and support for anticommunist insurgencies—the Reagan Doctrine—while neoconservatives in particular celebrate the combative rhetoric Reagan directed against Communism and his eventual support for democratic movements in the Philippines and South Korea. The Reagan administration’s foreign policy included all of these things, but they weren’t all desirable or successful.

How these factions interpret the same events during the Reagan years represents another way that the 40th president’s legacy is co-opted and reinvented in contemporary debates. The decision to send U.S. forces into Lebanon in the wake of the 1982 Israeli invasion and then the decision to remove them after the 1983 Marine barracks bombing in Beirut remain some of the most contested episodes from the Reagan years. The way that different factions on the right perceive Reagan’s Lebanon policy exposes the fault lines that divide them sharply from each other.

Noninterventionists and other conservative supporters of foreign-policy retrenchment view the withdrawal from Lebanon as an example of how Republicans can and should be willing to acknowledge a major policy error and correct it by avoiding additional American losses in unnecessary missions abroad. In 2011, Grover Norquist used the example of withdrawal from Lebanon as a model for how conservatives could agree to cut U.S. losses in Afghanistan and end that war sooner. During the 2008 and 2012 primaries, Rep. Ron Paul cited Reagan’s decision to pull troops out of Lebanon as proof that calls for terminating foolish interventions quickly had a good conservative and Republican pedigree.

The original decision to intervene in Lebanon stands as a warning for conservative noninterventionists that there is nothing to be gained for the U.S. by becoming involved in conflicts in countries whose history and internal divisions Americans don’t even begin to understand. Indeed, withdrawing U.S. forces from Lebanon had no significant harmful consequences for U.S. security. It was only much later, following the 9/11 attacks, that hawks put a new, implausible spin on the decision to leave Lebanon as an invitation to future strikes against us.

At its best, Reagan’s foreign policy was a response to contemporary realities and problems, and most of these no longer exist. Conservatives who fail to take these changes into account are substituting nostalgia for sound analysis. Instead of worrying about what Reagan would do today, conservatives should devise a foreign policy that advances U.S. security and interests in the world as it is. Rather than trying to relive the Reagan years, conservatives would do well to scrutinize which of Reagan’s decisions still make sense with the advantage of more than two decades of hindsight.

His most hawkish decisions as president make sense only in the context of the Cold War and have little or no application to contemporary issues. The U.S. has no superpower rival to contain any longer, and it faces no coherent ideological challenge on par with that of Soviet Communism. A military build-up comparable to Reagan’s today would serve no purpose except to bloat the Pentagon’s budget—and defense contractors’ wallets—to the detriment of America’s fiscal health. To the extent that Reagan-era increases in military spending contributed to Soviet collapse, they had some value, but it makes no sense to maintain military spending that exceeds even that of the Reagan era when no comparable foreign threat exists.

There is no longer anything to be gained by supporting insurgents against weak dictatorships, and no reason for the U.S. to embroil itself in the internal conflicts of other nations. Whatever value the Reagan Doctrine may have had in the 1980s, it now stands mostly as a cautionary tale about the damage that arming foreign insurgencies can do to the countries affected and the abuses that may come from waging such proxy wars. When there is nothing for the U.S. to “roll back,” there is no need for anything like a policy of rollback.

The most common abuse of Reagan’s legacy is the rote recitation of the slogan “peace through strength.” Originally, the phrase implied support for creating a strong defense as a deterrent to aggression. As the threat of aggression by other states has receded, it has come to mean something very different. Many Republican hawks rely on this phrase to describe their foreign-policy views, but they long ago dismissed the importance of deterrence when dealing with states much weaker than the Soviet Union. It is common now for advocates of regime-change and preventive war to profess their commitment to “peace through strength,” but the substance of the policies they prefer shows that they reject the concept as Reagan understood it both in principle and in practice. Instead of deterring aggression to protect international peace, the new “peace through strength” often serves as rhetorical cover for the violation of that peace through acts of aggression.

There is likewise little in common between Reagan’s actual foreign policy and the so-called “neo-Reaganite” foreign policy promoted by neoconservatives over the last 20 years. This is the approach Bill Kristol and Robert Kagan introduced in a 1996 Foreign Affairs article, which presented the case for U.S. “benevolent global hegemony.” The creators of “neo-Reaganite” foreign policy were determined to combat what they saw as insufficient conservative and Republican support for larger military budgets and an activist American role in the world. “Neo-Reaganites” wanted to “remoralize” American foreign policy, to make “moral clarity” its focus, and to “restore a sense of the heroic” to its conduct. In practice, this meant pushing for regime-change in some countries and meddling in the internal affairs of the rest. The Cold War had ended, but as far as “neo-Reaganites” were concerned, the only difference this made was that it freed the U.S. to be even more assertive in exercising global leadership.

The neoconservative use of “neo-Reaganite” as the brand name of their foreign policy was intended to signal to conservatives disaffected with George H.W. Bush’s domestic policy record that they should also reject the elder Bush’s more realist approach to world affairs in favor of a more militarized and moralistic one. If Bush had proved to be a poor heir to Reagan at home, the “neo-Reaganites” were saying, he must have “discarded” Reagan’s foreign-policy views as well by not being missionary enough. This deliberately obscured the extent to which Reagan had moved in the direction of the realists during his presidency, and it ignored how in response to this “neo-Reaganites” and their forerunners had constantly faulted Reagan for being too accommodating with the Soviets and too ready to negotiate and agree to arms reduction.

Sen. Rand Paul’s speech at the Heritage Foundation in February was an attempt to claim Reagan for the Republican realist tradition, but with the added twist of connecting Reagan’s record to George Kennan’s understanding of containment. Paul identified the link in the claim by Jack Matlock, a former Reagan national security official, that Reagan’s Soviet policy was closer to Kennan’s thinking than any president’s approach that had come before it. Matlock’s 2007 account of the views that Kennan and Reagan shared covered many different issues, but perhaps the most important point of convergence was on containment itself. Matlock wrote:

Both men rejected what Kennan called ‘liberationist slogans,’ those that had been used, particularly in 1952, to attack his containment policy. Reagan also refused to play the ‘nationality card,’ attempts to stir up the non-Russian population of the Soviet Union. While he thought that the independence of the Baltic countries should be restored, he did not set out to bring down the Soviet Union. He tried to change Soviet behavior, not to destroy the Soviet Union.

If there were important points of agreement between Reagan’s policy and Kennan’s thinking, Kennan himself was appalled by Republican triumphalism that sought to credit the Reagan administration and the GOP with winning the Cold War. In an October 1992 op-ed for the New York Times, Kennan dismissed the claim that the Reagan administration “won” the Cold War as “intrinsically silly.” He rejected the idea that an event as momentous as the dissolution of the USSR could be attributed to the actions of any American administration. Kennan wrote:

The suggestion that any Administration had the power to influence decisively the course of a tremendous domestic political upheaval in another great country on another side of the globe is simply childish. No great country has that sort of influence on the internal developments of any other one.

The idea that Reagan “won” the Cold War is one of the more pernicious and enduring distortions of Reagan’s real success, which involved both opposing and engaging with the Soviet Union as its system collapsed from within largely on its own. The claim of winning the Cold War greatly exaggerated the ability of the U.S. to shape events in other countries. That in turn has inspired later generations of conservatives and Republicans to imagine that they can successfully promote dramatic political change overseas in order to topple foreign regimes. As Kennan said in the same op-ed: “Nobody—no country, no party, no person—‘won’ the cold war. It was a long and costly political rivalry, fueled on both sides by unreal and exaggerated estimates of the intentions and strength of the other party.”

Congratulating Reagan for winning the Cold War is one more form of widespread abuse of Reagan’s legacy that has adversely affected how conservatives think about foreign policy and the proper U.S. role in the world. This has warped how the right understands American power and U.S. relations with authoritarian and pariah states for the last two decades. It also blinds many conservatives to the fact that other nations resent and reject American interference in their political affairs. In spite of the failures of nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan and the collapse of the so-called Freedom Agenda, this myth continues to make many on the right overly confident in our government’s ability to influence overseas political developments to suit American wishes.

The conservatism of the Cold War era was in large part defined by anticommunism, as this provided the common cause that united disparate groups on the right and informed their prevailing foreign-policy views. Ever since the end of the Cold War, conservatives have sought in vain to find something that might replace anticommunism, and they have tried to conjure up a new ideological foe that could fill the same role that Communism did for four decades. Many conservatives have sought to use the existence of jihadism as a justification for a new global ideological struggle, and even Senator Paul suggested something along these lines in his speech at Heritage with his comparison of “radical Islam” and the Soviet Union. Yet what is necessary for conservatives now is to stop conceiving of the U.S. as the leader of one side in a global ideological struggle, and that isn’t likely to happen so long as conservatives keep falling back on arguments about what Reagan did and what he would do today.

The conservatism of the Cold War era was in large part defined by anticommunism, as this provided the common cause that united disparate groups on the right and informed their prevailing foreign-policy views. Ever since the end of the Cold War, conservatives have sought in vain to find something that might replace anticommunism, and they have tried to conjure up a new ideological foe that could fill the same role that Communism did for four decades. Many conservatives have sought to use the existence of jihadism as a justification for a new global ideological struggle, and even Senator Paul suggested something along these lines in his speech at Heritage with his comparison of “radical Islam” and the Soviet Union. Yet what is necessary for conservatives now is to stop conceiving of the U.S. as the leader of one side in a global ideological struggle, and that isn’t likely to happen so long as conservatives keep falling back on arguments about what Reagan did and what he would do today.

Conservatives certainly can and should still learn from Reagan’s successes and mistakes—as they should from those of Nixon, Eisenhower, and other past leaders. However, if there is to be a conservative foreign policy that is well-suited to advancing present-day U.S. security interests, conservatives cannot continue relying on the crutch of imitating and invoking Reagan. If conservatives are supposed to understand and cope with the world as it is, rather than how it once was or how we would like it to be, nothing would be worse than to mimic a foreign policy that was created for another era.

Daniel Larison is a TAC senior editor. His blog is www.theamericanconservative.com/larison.

Comments