Texas Needs More Housing

Texas has been on my mind lately. When I think of the state, I generally think of a place resistant to regulation, open to innovation, and willing to take chances even if it annoys the rest of the country.

But as Earnest Tubb sang, there’s a little bit of everything in Texas—even the kind of thinking that too often prevails in policy debates about rising housing prices, rents, and home-improvement costs. Two recent articles and the situations they describe, one from Fort Worth and the other from Austin, show that even Texas is in the thrall of received wisdom on housing creation: pushing for more money rather than smarter rules. But there is hope that Texas can still lead the country on housing issues.

I was contacted by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram recently to comment on a story about 800 substandard houses in Fort Worth in need of renovation. Fort Worth nonprofits quoted in the story had an answer: more money. One advocate said it could cost as much as $10,000 to renovate homes to keep them livable. I have no idea where that number came from, but I went with it and did some simple math: Fixing up 800 houses at $10,000 a piece would cost $8,000,000.

Meanwhile, I guessed there was at least one big nonprofit publicly funded apartment project being built with subsidies in Fort Worth. Sure enough, the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA) website listed The Park Tower Project, a $22-million project funded using 9 percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). Tax credits are not fungible; you can’t spend a tax credit on a fancy new apartment building or renovating substandard houses for poor people, as the story from the Star-Telegram was describing.

But Texas should be able to do that. The Park Tower project has 90 units, which puts the per-unit cost at about $244,000. Of the 90 units, 78 are classified “affordable”—that is, the price is controlled by covenant. That accounts for $19 million of the project. More simple math: The costs associated with the 78 affordable units would cover about $20,000 worth of repairs to each of those 800 substandard houses.

After posting about this at Forbes, I was contacted by a public-relations firm, which first disputed my math (they were wrong), and then asked me to remove the company’s name (Housing Trust Group) from the post:

Also, given that there are so many affordable housing developers that utilize the LIHTC program – this is not unique to HTG – is it possible to actually just say “a developer” instead of calling out HTG by name? Obviously, our team is very pro-LIHTC programs so we don’t want the article to imply that we participated in this story – and doing so doesn’t fundamentally alter/detract from your story in any way. Please let us know!

Well, I did let her know—by rehearsing the middle-school math above and pointing out that not only did I find the project on the TDHCA website, but her own firm had promoted the project proudly in local business publication. I responded politely that this is exactly the problem with the housing market in this country—“this is not unique,” I said. Which is the better solution for 800 families living in substandard housing in Fort Worth: 78 units a few years from now, or $20,000 for repairs today? Unfortunately, the structure of the LIHTC program doesn’t allow for that option, and the TDHCA and HTG and all the other acronyms aren’t advocating for that to change—they’re just pushing for more and more money.

And speaking of more money, here’s a key paragraph in an editorial co-authored by former director of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Henry Cisneros on how Austin can avoid watching its housing prices rise as the city grows, from the Austin American-Statesman:

It is local governments that are best positioned to advocate for new resources and deploy them in creative, effective ways. While Austin has already done a lot of things right—passing an affordable housing bond ballot initiative, greenlighting federal COVID relief to fight homelessness, and making it easier to build accessory dwelling units—there is always more to do. Austin should leverage the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to defray the cost of critical infrastructure connected to new housing.

To be fair, Cisneros ends that paragraph with acknowledging that Austin should continue “to foster more expeditious, predictable development processes, update the city’s land development code, and preserve affordable housing for longtime residents.”

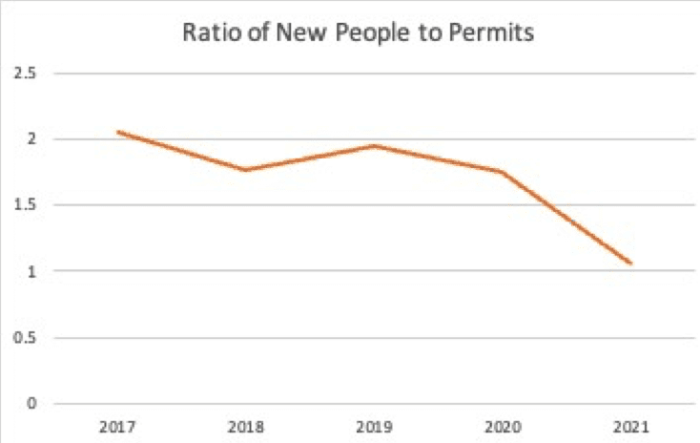

But has it done so? A look at data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis (FRED) indicates that the ratio of new people to permits has, indeed, fallen. The ideal ratio would be 1:1, with a new unit for each new person coming to Austin.

And a look at Zumper shows that rents have trended downward in the same period—until recently.

What accounts for this downward trend being followed by an uptick? My guess is that the number of permits recorded in the broader FRED data, which covers more than Austin proper, have kept up with population growth, and that while surrounding jurisdictions are issuing permits at an almost one-to-one basis, Austin itself hasn’t kept up. I found validation for this thesis from a deeper look at housing in Austin by the Cicero Institute:

The City of Austin also has problems with its general permitting process. In 2015 the 800-plus page “Zucker Report” demonstrated that the city’s then-Planning and Development Department, which permitted new housing projects, was sluggish, impenetrable, and anti-development (page 12).

Consider what Waylon Jennings sings of Texas in the last verse of his paean to Bob Wills:

It’s the home of Willie Nelson

The home of western swing

He’ll be the first to tell you

Bob Wills is still the king.

And so it is with housing supply. The best thing state and local governments in Texas can do to keep the state exceptional is to deploy a paraphrase of what Jennings sang: Whether by repairing existing homes or issuing permits, while you just can’t live in Texas unless you got a lot of soul, and along with soul, you just can’t live in Texas unless you got a lot of housing, too.

Roger Valdez is director of the Center for Housing Economics, a nonprofit housing research and advocacy organization, and a research fellow at the Foundation for Equal Opportunity (FREOPP).

The New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.

Comments