The Unsung Hero of American Air Power

WASHINGTON—The documentary played over the large projection screen at the head of the room. From a distance it was like the chronology of any other military battle: A narrative with an auspicious beginning, unsung heroes, stubborn enemy, and a prize.

But in this case it was the intramural service fight in the Pentagon to get a particular tactical aircraft, the A-10, off the ground in the Pentagon. The prize was keeping the Air Force from retiring the plane after what seemed to be a 40-year effort to do so. The heroes were the guys who envisioned, built, and protected it from the boneyard all these years.

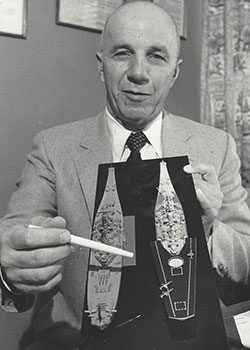

When Chuck Myers’ face first appeared on the screen there was a slight but palpable shift in the air hovering over the darkened conference room at the DC offices of the Project for Government Oversight. Myers was what Hollywood movies would call an irreplaceable member of the A-Team, known in this case as the “Fighter Mafia.” He passed away in May at age 91, and for some in the room earlier this month, it was the first time they’d seen his face since some of their previous conclaves there or at the Officers Club at Fort Myer.

There he was, a wizened WWII and Korean War combat flier, former test pilot, “bureaucratic guerilla warrior,” and A-10 godfather. Myers had done many, many rounds with the other services, particularly the Air Force, in defense of the close air support combat planes and lightweight fighters like the F-16 and F-18. He never retired from this mission. The film screened earlier this month, Against All Odds: The Story of the A-10, doesn’t capture all of the wonderful facets of Myers, but it provides a worthy entrance into the life of a man who long ago took the path of productive dissension within the military, and found comfort in his own skin doing so.

“He was a just a very dedicated person and he had enormous stamina. Physically and mentally, he was intense—I mean I talked to Chuck a maybe a week before he died, and this was before he had any sign of going into the hospital—and we were talking all about the military’s problems,” said James P. Stevenson, author of several books on fighter aircraft and the bureaucratic food fights around them. In The Pentagon Paradox: The Development of the F-18 Hornet, he introduces the Fighter Mafia, which also included math whiz and Pentagon analyst Tom Christie, aeronautics specialist Pierre Sprey, test pilot Col. Everest Riccioni, and strategist John Boyd, whose OODA (observe, orient, decide, act) Loop has made him a cult figure in a tightly bound community of scrappy Pentagon reformers.

“They had a moral compass that was always pointed at true north,” Stevenson added. “But with respect to spending taxpayers’ money, with respect to doing the best job to defend the United States, they are immovable. You could drop a million dollars in front of them and they would say, ‘get out of my way.’”

Two things appeared to motivate Myers and the rest of the Fighter Mafia crew, and they were not mutually exclusive: Keeping close air support programs like the A-10 alive, and keeping Pentagon procurement and acquisitions honest. They believe the “grunts on the ground,” need to be protected in combat, and they have always discerned, from the very beginning, an almost unholy alliance between the military bureaucracy and defense contractors to make costly planes and weapons systems at the expense of safety and tactical effectiveness. Not everyone agrees with them of course, and for some time the Air Force has been attempting to retire the A-10 (so far, unsuccessfully) in favor of its more all-purpose fighter, the F-35. But these guys have been rallying for the underdogs in such a methodical, relentless manner, that they have become unlikely icons of a much larger narrative.

“They are all superstars as far as I’m concerned,” Stevenson told TAC. Myers, he said, had a particular disdain for how the sausage was made, at one point likening contractors to prostitutes. “What is the difference between a prostitute and contractor?” he asked. “For one thing, a prostitute can do all the things contractors can’t deliver.”

For Myers, the fight for close air support for was born out of his own experience as an Army Forces fighter pilot during World War II. At the young age of 19 he flew B-25s in low-level attack missions against the Japanese. During the Korean War he flew F9F Panther jets for the Navy.

“From [WWII] on, Chuck always felt that the fighting guy on the ground was getting screwed and he was seeing the fighter pilots were being screwed from bad airplanes in the air. It was solidarity with the pilots and grunts—it was that simple,” offered Pierre Sprey.

Sprey was one of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s “whiz kids” who eventually became a self-described subversive in the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s systems analyses realm. Along with Christie and Boyd, he met Myers sometime around 1964, before Myers worked in the Pentagon.

“He was one of the earliest proponents of what we were doing with the lightweight fighter,” Sprey told TAC. He said in those early years, when Myers was working for Lockheed, he “had an interesting way of not becoming a complete shill.”

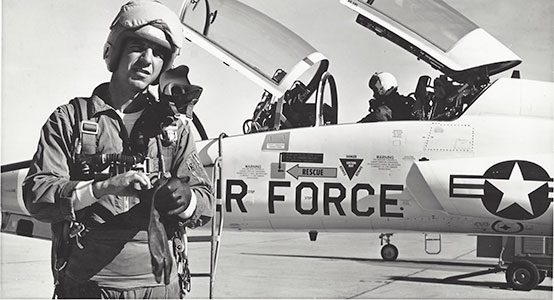

Of course, as a former test pilot, Myers was the only flier in the group, and brought with him access to an entire culture of experienced pilots and practical knowledge of air combat. Myers went to Navy Test Pilot School after Korea and graduated in 1954 in a class that included future astronaut John Glenn. He made his mark by setting the world record in 1960 for flying a Delta Dart 1,544 miles an hour, and later helped form the the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

“He had an extraordinarily interesting group of test pilot friends with combat backgrounds,” Sprey recalled, all of whom were working either in the Pentagon or the aerospace industry at the time.

“He was full of endless war stories, all of which were true,” said Sprey, who recalled how, when selling his concepts, Myers would take people out on an aerobatic airplane on his 600-acre Flying M Stock Farm in Gordonsville, Va.

“He’d show them what the ground looked like from the sky, he’d show them how hard it was to see anything from an airplane,” he said, noting the many “convivial seminars” they’d have out on the working farm.

“I was always much more confrontational,” he added, “but Chuck had a nice way of reaching out to people and getting his points across.”

After he left private industry to start his own consulting business in the late 1960s, Myers had the opportunity to join the Pentagon ranks and make a real difference in the services’ thinking about close air support and mission-specific aircraft. He was offered the position of Director of Air Warfare in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD procurement) in 1973. With his comrade in arms Christie in the TacAir shop (systems analysis) in the OSD, they had the ear of the secretary and the ability to get things done.

“Chuck and I teamed up to keep close watch on budget preparation and execution processes, stepping in to restore funding when the Air Force and their allies” attempted to remove it from their lightweight fighter and the A-10 prototype (A-X) programs, Christie told TAC.

“Chuck was critical in these continuing fights,” he noted. “If he had not been in that position … during those critical years between late 1973 and 1975, I am convinced we would have seen the LWF bite the dust and the A-X go down the tubes. He had the complete trust of (then Secretary) Jim Schlesinger, which did not endear him to” the Air Force leadership or many of his colleagues.

“He was a pretty much a maverick,” but he had the ability to make allies and sell these programs inside the establishment, said Sprey. “Chuck was staunch on these concepts,” but “in his nice, non-confrontational way, he got people in R&D on board who would normally be against it.”

After Schlesinger left the “long knives” came out for the A-10 and the F-16, but by that time both programs were well on their way to reality. Myers also left his mark on the future F-18.

That was the mid-70s—a generation ago. But Myers and his “cabal” continued for four decades to protect the A-10 and help build better planes aligned with their core interests—which became more and more divergent from that of the services. Amazing advances in radar communications and weapons systems have made planes more technical, all-purpose, and complex—and more expensive. They like to point to the troubled F-35 as a prime example.

During this time, Myers embarked on many personal projects and worked with Air Force and Marine officers who follow the Fighter Mafia code and John Boyd’s philosophies. The group, now far from the Mad Men days, are tight as ever, meeting in Arlington in the shadow of the Pentagon, and, until his death, at Myers’ farm where he lived with his wife of many years, Sallie.

But now they have acolytes: Vietnam, Persian Gulf, Iraq, and Afghanistan War veterans, as well as active duty and reserve officers and pilots. To see the reverence of the younger men and women in the room at the recent movie screening indicates that the message of that cabal has maintained its salience as the services fight over billions in defense dollars today.

“I don’t know anywhere else to go to find a group more dedicated to making things better,” Myers told this reporter a little more than three years ago.

“He was just a special person,” said Stevenson, who was bequeathed the gold watch Myers got from Convair when he beat the world record for a single-engine jet aircraft with the Delta Dart. The Air Force gave the official recognition to a service pilot who fell slightly short of Myers’ speed because during the Cold War, a uniformed officer made for a better story. Over the years, that watch had become a metaphor for hand-in-glove cynicism, where the military and the defense industry worked together to advance themselves, often at the expense of merit and the truth.

Chuck Myers “was primus inter pares,” said Stevenson, “first among equals.”

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos is a Washington, DC-based freelance reporter.

Comments