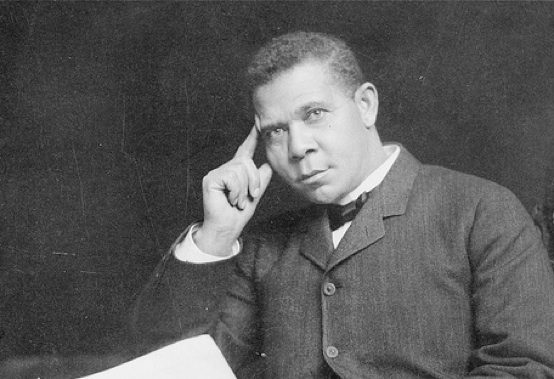

The Legacy of Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

Despite his prodigious career in education, Booker T. Washington’s legacy has been tarnished with a charged failure to do more for civil rights during his lifetime: Robert J. Norell, a historian and author of a recent biography on Washington’s life damned him as a “heroic failure”. In 1895, Washington delivered a speech that would be known as the Atlanta Compromise: a short address to allay white fears of a black uprising in a postbellum South. It was delivered to a mostly white audience at the Cotton Sates and International Exposition in Atlanta concerning the current state of black men and women in the South, their place in society, and their future as citizens in the country that once held them as property. “…[Y]ou can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people that the world has seen.” Though the language may have been obsequious, if one reads between the lines and flowery phrases, Washington’s address contained a warning about the protracted denial of the black man of his identity in the South—a warning that was brought to pass through Washington’s ideological descendants.

A child at the end of the Civil War, Washington understood from a young age the importance of self-sufficiency among the black community. When all the slaves of his plantation were set free, after the initial celebration, the sobering reality of planning a future for themselves and their children set in. Washington wrote in his autobiography Up From Slavery: “The responsibility of being free, of having charge of themselves, of having to think and plan for themselves and their children, seemed to take possession of them.” The elderly slaves in particular felt the most vulnerable, and rightly so. After spending nearly all of their lives working on a plantation, they stood to gain the least from freedom. They had neither the strength to leave the plantation or the skill to work elsewhere. Their freedom was only nominal, and would never be fully realized.

Washington’s solution to this new crop of citizens whose only background was plantation work was practical education. After taking the helm of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881, Washington focused his energy on ensuring that blacks had access to both vocational and moral training. Washington believed in the value of blacks being able to provide for themselves by the work of their own two hands with neither resentment nor entitlement.

His views were not universally welcomed among blacks—especially not among the intelligentsia. One of the most prominent black intellectuals of his time, W.E.B. DuBois, denounced Washington’s views and demanded that blacks be fully reinstated with access to education, health care, jobs, and the right to vote. Eloquent, sophisticated, and respected in social and academic circles, DuBois found Washington’s philosophy about black education anathema to the black American cause. But geography and time separated the two men. DuBois was born and educated in the North, where slavery was abolished first and where Quakers and other religious groups preached equality. Washington’s world was the deep South, where slavery had persisted for hundreds of years, blacks were not yet regarded as fully human, and lynchings were an acceptable way to deal with “uppity” blacks.

Though DuBois and Washington are presented in history as diametrically opposed, the dichotomy portrayed on paper is false. Newly surfaced evidence suggests that Washington very much believed in equal right for black Americans, but used backdoor channels to convey his convictions. He wrote about his beliefs in civil rights under a pseudonym and donated to organizations that promoted equality for blacks. Washington’s idealism came second to his relentless pragmatism and an understanding of the times he lived in. In light of the Restoration and continued violence against blacks, Washington knew better than to rock the boat. He was one of the few black men of his time who was invited into white organizations to speak—and was the first black man to have dinner at the White House. It is reasonable to suspect that in order to maintain his influence, Washington felt openly discussing politics in such a tender environment less than a generation away from slavery was a risk he was not willing to take.

It is easy to point out the flaws in a system and demand retribution for obvious wrongdoing; it is much more difficult—and admirable—to suggest that two groups of people whose interdependent history is charged with violence live alongside each other in peace, and commanding the oppressed group to make the first move. By advocating the virtues of skilled work and not taking an eye for an eye, Washington gave his blacks a legacy that DuBois never could: a moral basis for resistance. Decades later, after blacks had been working diligently in the service and labor industries but were still denied the most basic rights granted to citizens, the political tide eventually turned. Washington was concerned with making sure that blacks would be prepared to accept the responsibility that came with the rights they asked for rather than make demands that would prolong conflict with no end in sight.