Warren’s DNC Speech Was Compelling, and Absurd

Though it was quickly overshadowed by the big-ticket appearances of Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren’s Tuesday address to the Democratic National Convention deserves some consideration.

A probable VP nominee before the events of the summer made race the deciding factor, Warren is an able representative of what might be called the “non-socialist populist” branch of the Democratic Party. Her economic populism—though it does have an unmistakably left-wing flavor—has caught the eye of Tucker Carlson, who offered glowing praise of her 2003 book The Two-Income Trap; her call for “economic nationalism” during the primary campaign earned mockery from some corners of the Left and a bit of hesitant sympathy from the Right. A few days ago in Crisis, Michael Warren Davis referred to her (tongue at least somewhat in cheek) as “reactionary senator Elizabeth Warren.”

There is some good reason for all of this.

As I watched the first half of Warren’s speech (before she descended into the week’s secondary theme of blaming the virus on Donald Trump) I couldn’t help but think that it belonged at the Republican National Convention. Or, rather, that a GOP convention that drove home the themes addressed by Senator Warren on Tuesday would be immensely more effective than the circus I’m expecting to see next week.

Amid a weeklong hurricane of identity politics sure to drive off a good number of moderates and independents, Warren offered her party an electoral lifeline: a policy-heavy pitch gift-wrapped as the solution to a multitude of troubles facing average Americans, especially families.

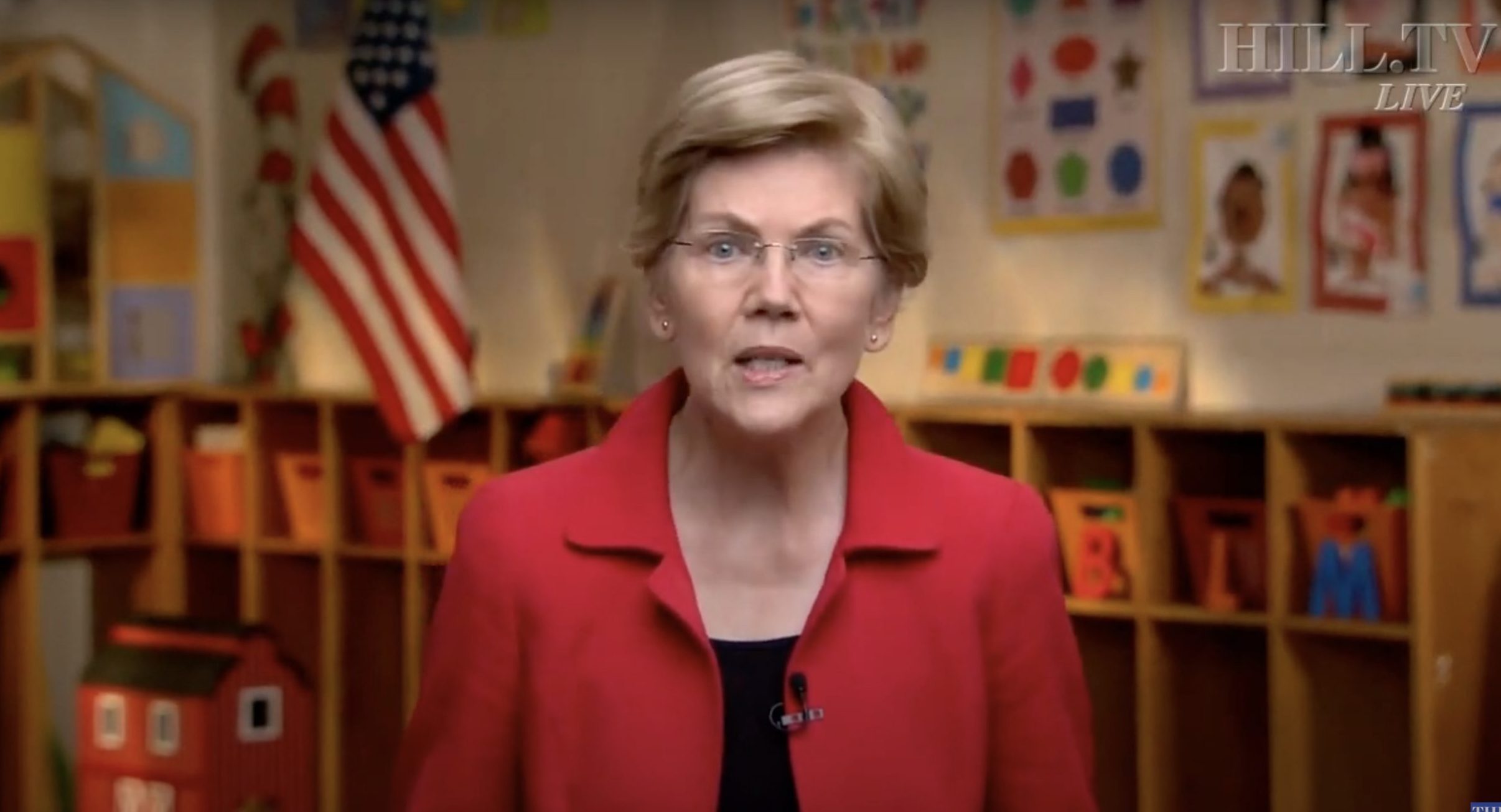

It was rhetorically effective in a way that few other moments in the convention have been. Part of this is due to the format: a teleconferenced convention left most speakers looking either like bargain-bin Orwell bogeymen or like Pat Sajak presenting a tropical vacation as a prize on Wheel of Fortune. But Warren, for one reason or another, looks entirely at home in a pre-school classroom.

The content, however, is crucial too. Warren grounded her comments in experiences that have been widely shared by millions of Americans these last few months: the loss of work, the loss of vital services like childcare, the stress and anxiety that dominate pandemic-era life. She makes a straightforward case for Biden: his policies will make everyday life better for the vast majority of American families. She focuses on the example of childcare, which Biden promises to make freely available to Americans who need it. This, she claims, will give families a better go of things and make struggling parents’ lives a whole lot easier.

It’s hard not to be taken in. It’s certainly a more compelling sales pitch than, “You’re all racist. Make up for it by voting for this old white guy.” It’s the kind of thing that a smart campaign would spend the next three months broadcasting and repeating every chance they get. (The jury is still out as to whether Biden’s campaign is a smart one.) This—convincing common people that you’re going to do right by them—is the kind of thing that wins elections.

But there’s more than a little mistruth in the pitch. Warren shares a touching story from her own experience as a young parent, half a century ago:

When I had babies and was juggling my first big teaching job down in Texas, it was hard. But I could do hard. The thing that almost sank me? Child care.

One night my Aunt Bee called to check in. I thought I was fine, but then I just broke down and started to cry. I had tried holding it all together, but without reliable childcare, working was nearly impossible. And when I told Aunt Bee I was going to quit my job, I thought my heart would break.

Then she said the words that changed my life: “I can’t get there tomorrow, but I’ll come on Thursday.” She arrived with seven suitcases and a Pekingese named Buddy and stayed for 16 years. I get to be here tonight because of my Aunt Bee.

I learned a fundamental truth: nobody makes it on their own. And yet, two generations of working parents later, if you have a baby and don’t have an Aunt Bee, you’re on your own.

Are we not supposed to ask about the fundamental difference between Elizabeth Warren’s experience decades ago and the experience of struggling parents now? Hint: she had a strong extended family to support her, and her kids had a broad family network to help raise them. Not too long ago, any number of people would have been involved in the raising of a single child. (“It takes a village,” but not in the looney Clinton way.) Now, an American kid is lucky to have just two people helping him along the way. As we’ve all been reminded a hundred times, the chances that he’ll be raised by only one increase astronomically in poor or black communities.

Shouldn’t we be talking about that? Shouldn’t we be talking about the policies that contributed to the shift? It’s a complex crisis, and we can’t pin it down to any one cause. But a slew of left-wing programs are certainly caught up in it. An enormous and fairly lax welfare state has reduced the necessity of family ties in day-to-day life to almost nil. Diverse economic pressures have made stay-at-home parents a near-extinct breed, and left even two-income households struggling to make ends meet. (Warren literally wrote the book on it.) Not to mention that the Democrats remain the party more forcefully supportive of abortion and more ferociously opposed to the institution of marriage (though more than a few Republicans are trying real hard to catch up).

Progressive social engineering has ravaged the American family for decades, and this proposal only offers more of the same. It’s trying to outsource childcare to government-bankrolled professionals without asking the important question: Whatever happened to Aunt Bee?

Republicans need an answer. We need to be carefully considering what government has done to accelerate the decline of the family—and what it can do to reverse it. Some of the reformers and realigners in the party have already begun this project in earnest. But it needs to be taken more seriously. It needs to be a central effort of the party’s mainstream, and a constant element of the party’s message. Grand, nationalistic narratives about Making America Great Again mean nothing if that revival isn’t actually felt by people in their lives and in their homes.

If we’re confident in our family policy—and while it needs a good deal of work, it’s certainly better than the Democrats’—we shouldn’t be afraid to take the fight to them. We should be pointing out, for instance, that Warren’s claim that Biden will afford greater bankruptcy protections to common people is hardly borne out by the facts: Biden spent a great deal of time and effort in his legislative career doing exactly the opposite. We should be pointing out that dozens of Democratic policies have been hurting American families for decades, and will continue to do so if we let them. We should sell ourselves as the better choice for American families—and be able to mean it when we say it.

If we let the Democrats keep branding themselves as the pro-family party—a marketing ploy that has virtually no grounding in reality—we’re going to lose in November. And we’re going to keep losing for a long, long time.

Comments