Selfies for Uncle Sam

If you use social media or have a smartphone, chances are you’ve encountered facial recognition technology. FRT allows computers to recognize pixel patterns that suggest human faces, allowing selfie-taking cameras to mugshot-filled databases alike to distinguish when they are looking at human faces. Even though it is fairly commonplace, some would rather avoid it, leading to one journalist’s experiment with clownish black-and-white makeup on the streets of D.C.

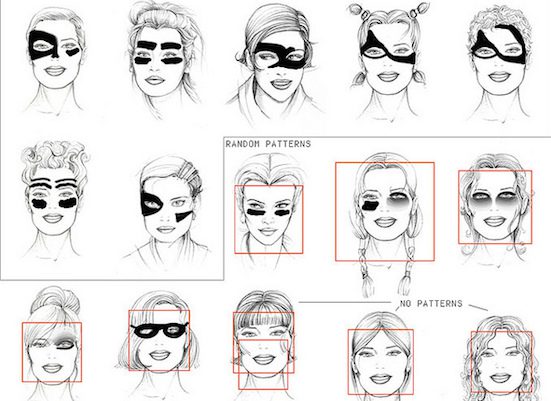

Robinson Meyer, an associate editor at The Atlantic, tried a camouflage technique called computer-vision dazzle, or “CV dazzle,” which uses face paint and hairstyling to stymie FRT. The makeup deceives FRT by obscuring the eyes, symmetry, and the nose bridge, among other features that characterize the face. “Here was a technology that confounded computers with light and color,” Meyer reflected. But as he learned, CV dazzle is far from a guarantor of privacy. “The very thing that makes you invisible to computers makes you glaringly obvious to other humans.”

Nancy Szokan alarmingly theorized that Meyer’s camouflage experiment is “something a terrorist might want to do”: escaping government surveillance. But in reality, Meyer’s experiment mainly resulted in evading Facebook auto-tagging, a seemingly tame privacy threat. FRT is routinely employed in the private sector beyond social media, from catching cheating gamblers to providing security at large sporting events like the Super Bowl. Now, its capacity to foretell age has stirred interest in insurance companies, while its real-time entrepreneurial applications are being explored by advertisers.

But when it comes to FRT falling into the wrong hands, concerns are generally directed at the authorities rather than vice versa. Though FRT has existed in its most basic form since the 1960s, it has blossomed under the biometrics industry fueled by the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, where the need to identify local populations induced the military development of portable biometrics systems. The government has enthusiastically inserted FRT into more routine use with increasing success: it shows up alongside other biometrics at airports and is now being introduced into police detective use. As Sameer Padania noted at Witness.org, “Law enforcement and security services particularly like FRT, as it does not require consent or knowledge of the subject being processed – unlike finger-printing, iris-scanning or similar biometric technologies, this can be done at a distance.”

It’s not the technology that is a major concern, Padania went on.

What’s new is this: this technology, which used to be accessible only to a few agencies, is now being used voluntarily, and unwittingly by millions of us through our use of social media. Our willingness to tag people in photos, and rapid advances in computer vision and object recognition have accelerated the use of FRT. We share so many images now that Facebook has, as this chart shows, the largest photo collection in history.

This voluntary engagement with FRT, which facilitates its intersection of cloud computing, is where change is beginning to occur. Jared Keller explained that the public’s increasing tech savviness opens the doors to “criminal, fraudulent, or extralegal ends” that are “as alarming as the potential for government abuse.” When private citizens organized a Google group to combine FRT with public records in search of identifying London rioters, they illustrated a new model of digital vigilantism.

The question, Keller says, is not how to escape FRT, whether donning masks or makeup. The question is how to live with it. “No matter what you choose to do or not to do, your life exists in the cloud. …Your digital life is becoming inseparable from your analog one. You may be able to change your name or scrub your social networking profiles to throw off the trail of digital footprints you’ve inadvertently scattered across the Internet, but you can’t change your face. And the cloud never forgets a face.”

CV dazzle may not become haute couture overnight. But surrendering selfies to Uncle Sam might, without anyone noticing.

Comments