Reclaiming Our Culture

A new book on books guides conservatives through the Western literary heritage.

13 Novels Conservatives Will Love (but Probably Haven’t Read), by Christopher J. Scalia, Regnery, 314 pages, $32.99

We conservatives are so used to being beaten down by the prevailing culture that we too often fail to look for anything of value within it.

For many on the right, the only books worth buying are those penned by the personalities on Fox News, and the only movies worth watching are on the order of Sound of Freedom or the biopic Reagan. To be sure, in an environment in which normal values are under persistent and undisguised attack, conservatives are not wrong to seek out what they perceive as friendly content, but in the process, they are too often ceding the glories of Western civilization that are theirs to claim. To put it another way, if the ideas on the right really are right, they will inevitably permeate most good works of art notwithstanding the political preferences of their makers or their mainstream fans.

One such maker, John Updike, in his 1989 Commentary essay “On Not Being a Dove,” identified himself as a Democrat; he couched his temperamental conservatism chiefly in terms of a boyish affection for the fatherly figure of LBJ and his support for the establishment that had embarked, however clumsily, on the Vietnam War: “I... felt obliged to defend Johnson and Rusk and Rostow, and then Nixon and Kissinger, as they maneuvered, with many a solemn bluff and thunderous air raid, our quagmirish involvement and long extrication.” Updike, in his intriguing quasi-conservatism, would hardly have checked the boxes for Conservative Inc. Were he alive today, he would still be published by Knopf, not Skyhorse. Updike may have been a contrarian among his liberal class, but he was not a traitor to that class.

Yet while reacquainting myself with Updike’s classic short story “Packed Dirt, Churchgoing, a Dying Cat, a Traded Car,” first published in the New Yorker in 1961, it occurred to me that only conservatives could apprehend his intentions in this beautiful story—especially my favorite section, “Churchgoing,” which commends the practice of attending divine worship in wonderfully practical, concrete terms. “Taken as a human recreation, what could be more delightful, more unexpected than to enter a venerable and lavishly scaled building kept warm and clean for use one or two hours a week and to sit and stand in unison and sing and recite creeds and petitions that are like paths worn smooth in the raw terrain of our hearts?” writes Updike, who goes on to capture the ineffable coziness and security of a church body gathering for a midweek Lenten service amid an unfriendly world: “The nave was dimly lit, the congregation small, the sermon short, and the wind howled a nihilistic counterpoint beyond the black windows blotted with garbled apostles.”

Updike’s insights and concerns would be unintelligible, if not incomprehensible, to the average atheistic, pronoun-sharing modern reader of literary fiction. Yet they are very much in tune with conservatives of every ilk, whether or not Updike (or Walker Percy or John Cheever or Norman Mailer) might have had any sympathy with or comprehension of MAGA. The lesson: Conservatives should plunder art made by official or apparent liberals.

This is approximately the argument of the American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Christopher J. Scalia, who opens his new book 13 Novels Conservatives Will Love (But Probably Have Never Read) with an exhortation for his right-minded brethren to expand their literary horizons. Scalia rebukes conservatives for clinging to a small subset of ideologically pure novels, “the same handful of works” that includes such mainstays as The Lord of the Rings or Atlas Shrugged. “The problem is that our reliance on them obscures the significance and abundance of conservative ideals and principles in literature more broadly,” Scalia writes. “The result is a sort of self-inflicted myopia to many cultural contributions of our ideological predecessors, and even of the exemplary literary expressions of our shared beliefs from writers who probably would not call themselves conservatives. We stand on the shoulders of giants—but there are more giants than we realize.” To this I would only add that while many such writers would definitely not call themselves conservatives, they end up reflecting our philosophy involuntarily, because they are perceptive about human nature.

Scalia’s is an eminently salutary project, and, although he does not include Updike among his giants, he happily steers clear of established conservative-friendly authors, like the above-referenced Tolkien and Rand, and weights the text toward his own personal enthusiasms. “These are all books I enjoy,” he writes, “which means my choices may strike some readers as idiosyncratic or just plain weird.”

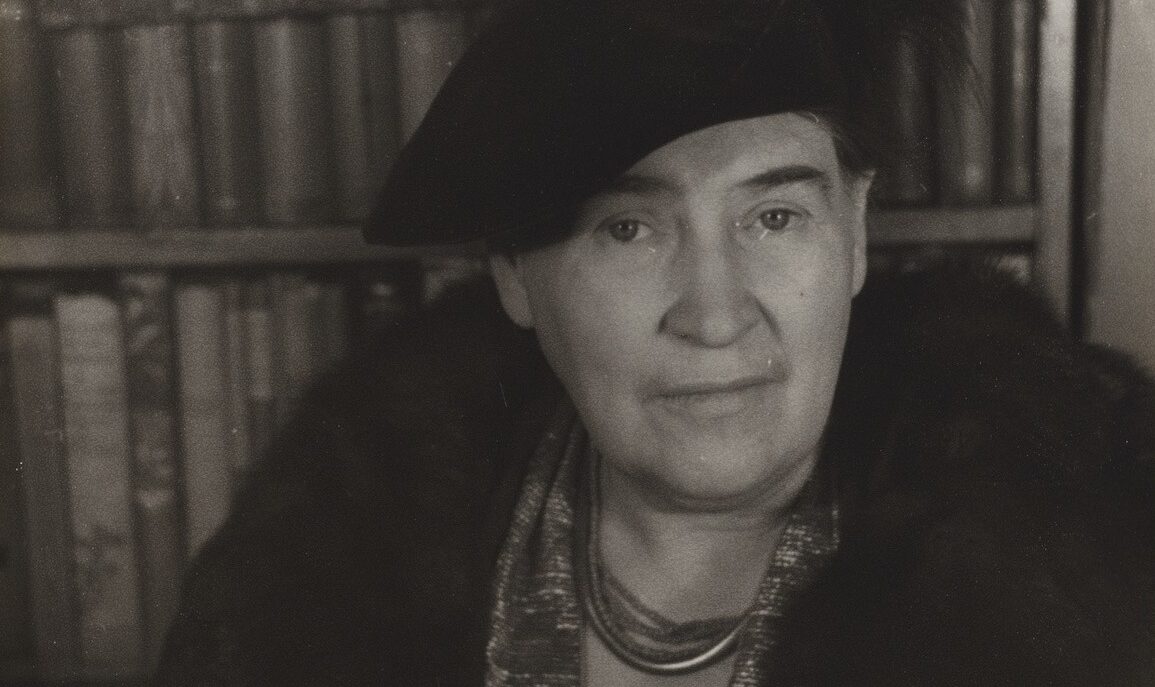

Consequently, a conservative favorite like Jane Austen is omitted (“The choir that is perpetually singing her praises does not need me to join the chorus”) in favor of the more provocative, daring choice of Willa Cather, whose ideological ambiguity Scalia describes perceptively. For the left, Scalia writes, “Cather’s life and works were most notable as expressions of feminist and (eventually) lesbian points of view,” while for conservatives, the author’s antagonism toward the New Deal and “sympathetic depiction of Catholics” have been enduring entry points to her fiction. Burrowing deeply and thoroughly into the themes of Cather’s masterpiece My Ántonia, Scalia concludes, without ever forcing the point, that the novel’s focus on “Ántonia’s happiness and the joy she has found in her life at home while raising a large family” renders it tacitly conservative. This is typical of Scalia’s approach: He susses out a book’s relevance to the conservative conception of life without straining or making claims the text cannot support.

Equally fine is the chapter on Muriel Spark’s novel about a clutch of young women who dwell in a wartime boarding house, The Girls of Slender Means. Stressing Spark’s conversion to Catholicism—after which, she said, “I began to see life as a whole rather than as a series of disconnected happenings”—Scalia refers to the novel as “a martyr mystery” for its preoccupation with a male character who is fated to have a consequential religious experience. “The Girls of Slender Means is a haunting story of conversion, the presence of evil, and the meaning of grace,” he concludes. Scalia’s choice of this author and this work suggests how much he is trying to break literary-minded conservatives out of their established habits: Among great Catholic convert writers, one is far more likely to read appreciations of Graham Greene or Walker Percy than Spark.

One of the most appealing things about Scalia’s book is the scope of its survey. Arranged chronologically, he begins in 1759 with Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas and works his way up to the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Among the modern novels in which he finds conservative ideas or notions, P.D. James’s novel The Children of Men, published in 1992, emerges as most urgently related to the concerns of present-day conservatives. As Scalia argues, James’s account of an involuntarily childless society, in which dolls and pets fill the void left by natural offspring and romantic relations are dulled in the process, mirrors conditions in this third decade of the 21st century.

“In the English dystopia of the novel, sterility is not a choice; childlessness is a plague,” he writes. “In the real world, childlessness is a priority.... Perhaps the despair and sadness of this novel’s childless world can remind us of just how invigorating and beautiful (and I know, exhausting, too) new life is.” Incidentally, Scalia identifies as “remarkably conservative” James’s own characterization of her day job as a mystery writer: “What the detective story is about is not murder but the restoration of order”—just the sort of insight that makes this book so refreshing.

Scalia locates themes consistent with conservatism in everything from Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God to V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River, and if the inclusion of Evelyn Waugh’s canonically conservative Scoop is a bit more predictable, at least his understanding of it is sharp and his appreciation sincere. “It’s notable that the main target of Waugh’s satire is not the political bias of reporters, but their laziness and groupthink—precisely the sorts of things that might lead to bias, but are nonetheless distinct from it,” Scalia writes.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Sincere in his goal to facilitate greater conservative involvement in classic literature, Scalia includes as appendices book-by-book discussion questions (“Over the course of the novel, to what degree do you find yourself sympathizing with the Jacobite cause? The Highlanders? Why?” he helpfully asks of Walter Scott’s Waverly) and ample suggestions for further reading, the latter of which reveals the depth and breadth of the alternative conservative canon.

If a reader enjoyed Scoop, Scalia commends P.G. Wodehouse’s Code of the Woosters, Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, and Christopher Buckley’s Thank You For Smoking; if a reader cottoned to The Girls of Slender Means, he proposes James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, and Spark’s own A Far Cry from Kensington. (This appendix includes many of the more predictable titles that a lesser author would have incorporated into the main body of the book, including not just The End of the Affair but The Bonfire of the Vanities and Gilead and such.) The timing of this book’s arrival could not be more fortuitous as many people use the summer months to catch up on their avocational reading.

The lesson of this engaging, useful book is for conservatives to redefine their sense of winning even in the ascendant second Trump administration: Retaking Nathaniel Hawthorne or George Eliot as our own may be more important than reshaping trade policy. Scalia writes, “A conservatism that is at once thoughtful and energetic, that is both committed to ideas and what Calvin Coolidge called ‘anxious for the fray,’ must know and perpetuate great works of art, including fiction.”