Movement to Movement

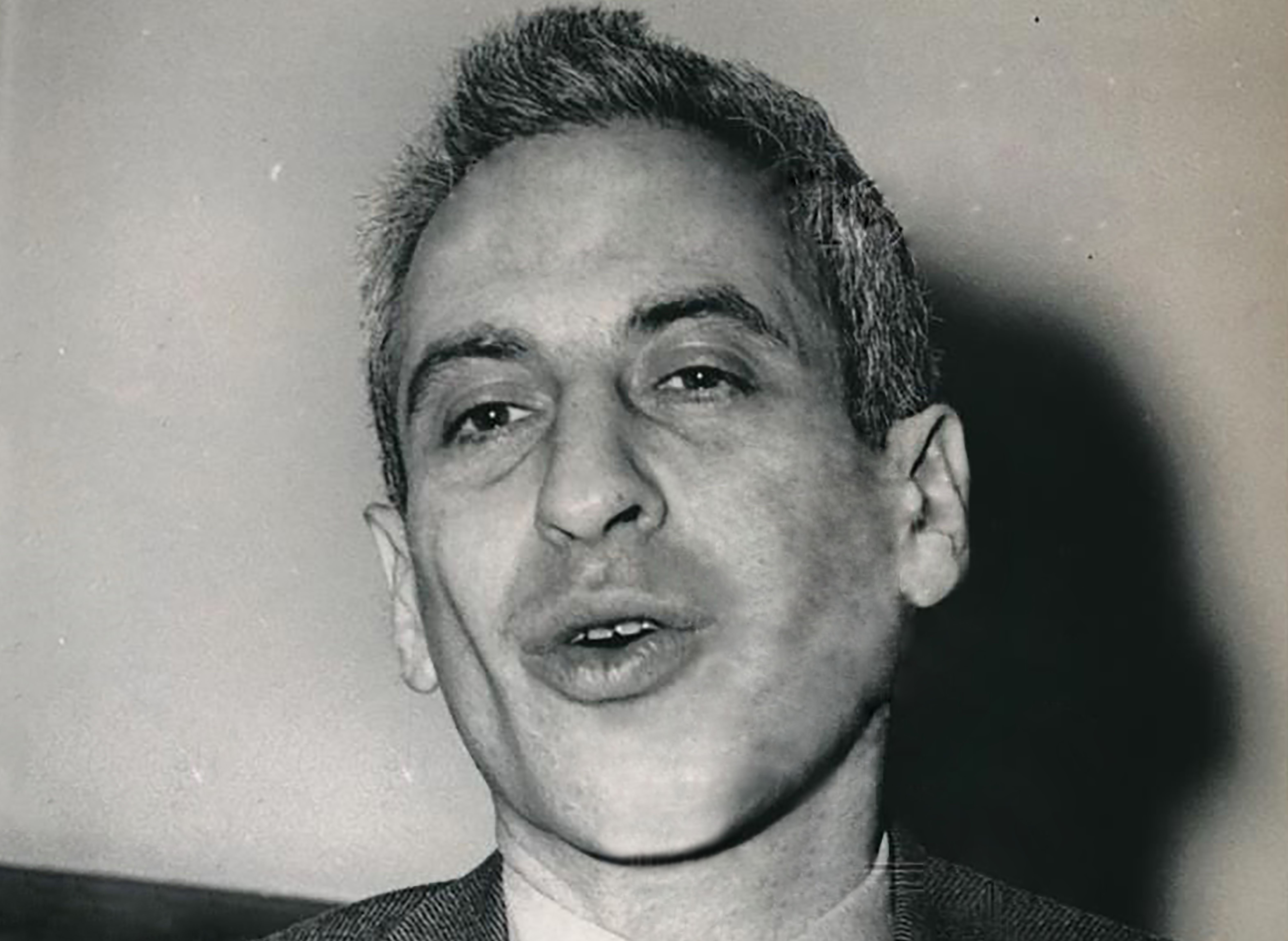

Frank Meyer’s journey took him from communist agitator to conservative kingmaker.

The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer, by Daniel Flynn. Encounter Books, 440 pages.

In 1981, Ronald Reagan spoke at the annual meeting of the Conservative Political Action Conference. Reagan reminisced about a number of conservative thinkers who had helped to lay the groundwork for his landslide election a year earlier, mentioning such worthies as Russell Kirk and James Burnham, both of whom were regular contributors to the journal that William F. Buckley, Jr. had founded in 1955, National Review. But Reagan reserved special attention for another editor at that journal—one Frank Meyer, who had made the “awful journey that so many others had: He pulled himself from the clutches of ‘The God That Failed,’ and then in his writing fashioned a vigorous new synthesis of traditional and libertarian thought—a synthesis that is today recognized by many as modern conservativism.”

Who was this Jewish former radical turned conservative that Reagan extolled with such fervor? In his biography, The Man Who Invented Conservatism, Daniel J. Flynn traces Meyer’s improbable intellectual and political odyssey. Flynn is a senior editor at the American Spectator and a Hoover Institution visiting fellow. Throughout, he sets the flamboyant and argumentative Meyer in the wider context of the American right, contending that he created much of the intellectual blueprint for its eventual rise. A gifted writer and assiduous researcher, Flynn explains that he discovered a large cache of Meyer’s papers in an abandoned soda warehouse in Altoona, Pennsylvania; these permitted him to reconstruct his life in copious detail. The result is a revelatory book.

Meyer, who was born in 1909 in Newark, New Jersey, grew up in a wealthy Jewish family that sent him to a posh Christian prep school. In 1926, it recommended him to Princeton University as someone whose “racial characteristics are unmistakable” but would be “an inoffensive member of the college community.” Meyer flamed out in his first year, earning poor marks and casting himself as a rebel against capitalism. After he was expelled from Princeton, Meyer sailed for England in 1928, intent on entering Oxford or Cambridge. After working with a crammer, he won entry to Balliol, where he soon cut a prominent figure as a Marxist radical, almost singlehandedly converting hundreds of students to Marxism–Leninism. (It’s worth noting that a few years later, another key figure in the conservative movement, Willmoore Kendall, would attend Pembroke College, where he became a Trotskyist, a saga acutely chronicled by Christopher H. Owen in his book Heaven Can Indeed Fall).

In 1931, Meyer cofounded the October Club, a Marxist groupuscule that benefitted, Flynn writes, from “someone as uniquely suited to convert others as this dark-eyed personification of surety, magnetism and intellect.” His organizational flair and fealty to Bolshevik ideals soon earned him a seat on the board of Great Britain’s Communist Party, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Kremlin. The 23-year-old was moving in other, rarefied circles: He encountered Albert Einstein, enjoyed a dinner with the former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and met T.S. Eliot, who apparently made approving noises about several of his poems. But in 1934, Meyer was once more expelled—this time from England, where his communist activities had caught the attention of the British secret service.

Upon returning to America, he remained a true believer. “I was formally a graduate student,” Meyer later recalled, “but mainly a party functionary.” He set up shop at the University of Chicago, where he became a campus celebrity and lackluster scholar. Once again, he ended up being expelled by a university. “In the thirteen years since his high school graduation,” Flynn notes, “he had attended six different institutions and attained just one degree. The euphoria of his front-row seat on the movement’s ascent during its halcyon decade obscured in real time the opportunities discarded.”

Like Irving Kristol, he discovered that entering the Army after Pearl Harbor in December 1941 dispelled many of his illusions about constructing a Marxist utopia. “His first key experience,” his son John Meyer observed, “was finding out that ordinary Americans in the military were not the proletariat they were cut out to be in Communist theory.” In 1943, Meyer began to take his first tentative steps away from Marxist dogmatism, maintaining that a fusion could be created between the American tradition and Marxism. He found a receptive audience in the form of Earl Browder, the head of the American Communist Party. “Browder reimagined American Communism,” Flynn reports, “as part of a broader left-of-center coalition rather than a sectarian political subservient to Moscow.” It was the Popular Front of the 1930s all over again. In 1946, on Moscow’s orders, the American Communist Party ended up expelling Browder for heretical deviations. Meyer soon followed. In Woodstock, New York, he went underground, but this time to avoid the party’s tentacles.

He began talking to the FBI in 1947 and testified a year later in the Smith Act trial of leading American communists. It offered him a megaphone to declare publicly his break with the party. “It did not so much mark the coda for one tune in his life as it did strike the opening note of another,” Flynn writes. “He spent the next decade naming names.”

It was his association with National Review that provided the capstone to his conversion to the right. Like Willmoore Kendall, James Burnham and Willi Schlamm (who met Lenin at age 16 in the Kremlin), Meyer was an apostate turned avenger. He now viewed the “decisive front,” as he put, as “the field of ideas.” In 1961, he published The Moulding of Communists, an expose of communist propaganda techniques. Though Meyer had shed his previous existence as an organizer, Whittaker Chambers, who functioned as a kind of mentor to Buckley, was convinced that Meyer had retained more than a little of the mental structure and ideological thinking of his earlier fling with Marxism–Leninism.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Others agreed. Robert Baumann, an early chairman of Young Americans for Freedom, recollected that Meyer attempted in essence to Bolshevize conservatism. After reading The Moulding of Communists, Baumann said, “I remember thinking at the time, ‘Well, this is where Frank got all his mojo,’ from all this backbiting and destruction and so on.” At the same time, Meyer sought to distill the conservative credo into a set of maxims or, if you prefer, principles that would create a kind of conservative Popular Front. This occurred in 1960 with the appearance of the extraordinarily influential 368-word Sharon Statement, which was drafted by Meyer’s disciple, M. Stanton Evans. It sought to fuse traditionalism, libertarianism, and anti-communism. By 1965, Flynn writes, Meyer may have failed to overthrow the British monarch and replace Franklin Roosevelt with Earl Browder. But in Flynn’s judgment, he did succeed in reshaping the America right: “Frank Meyer, Communist commissar, had finally ascended to conservative pope.”

One of the more interesting aspects of Meyer’s thinking that Flynn goes on to limn is his conviction that not only was victory over the Soviet Union probable, but it would usher in a new era in American foreign policy that heralded a return to older traditions. In a 1971 debate with the former Congressman Allard Lowenstein at Yale University, Meyer averred that, absent the Soviet threat, he would “oppose the war in Vietnam, I would oppose all alliances, any sort of foreign aid and participation in the United Nations.” In the same year, he wrote an essay titled “Isolationism?” In it, he suggested that Warren Harding had been unfairly mocked for espousing a return to normalcy; rather, his policy reflected a potent rejoinder to a “ludicrous Wilsonian crusade and a return to the world of reality.”

Flynn maintains that posthumously Meyer looks less like a pundit than a prophet. He foresaw the political realignment of America, writing in 1954 of a coming coalition of traditional Republicans and southern Democrats. He predicted the rise of the right and the collapse of the Soviet Union. He died in April 1972, decades before it disappeared. But in his remarkable conspectus of Meyer’s life, Flynn ensures that his pivotal role in reinventing conservatism does not go unappreciated or forgotten.