Marvin and Motown in Melbourne

There are times when any Melbourne inhabitant of at least average sentience feels like giving up on the city. Automobile traffic is increasingly nightmarish, urban mass transit increasingly erratic, real estate increasingly overpriced. Since 2008 Victoria has had the vilest pro-abortion laws in Australia, comparable with the very worst in other Western countries.

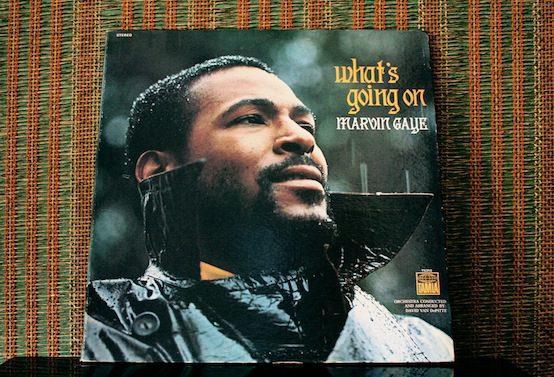

But just as it becomes tempting to shake Melbourne’s dust off your shoes, some local organization does something profoundly right. Thus it is that the downtown Athenaeum Theater has begun treating us to Motown magic, via a Marvin Gaye tribute show in which more than a dozen of the label’s hits are rendered with, ahem, “precious love.”

The chief burden falls on the extraordinarily gifted young actor Burt LaBonte, who understandably enough reverts to his natural Australian accent in spoken passages, but who in song is … scarily authentic. Shut your eyes when he delivers “What’s Goin’ On?” or “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” and you will swear that it actually is Marvin, magically reincarnate. Seemingly effortless in his upper register, he nails phrase after phrase in bona-fide style, yet never for a moment resembles a mere dutiful mimic. His colleague Jude Perl is perhaps huskier and more contralto-like than, in the best of all possible worlds, the analogue to Tammi Terrell and Diana Ross would sound. But there is nothing at all inherently deficient about her set of pipes, any more than LaBonte’s. And in the show’s most daring single stroke, it is Perl, not LaBonte, who gets to spit out what must be the most menacing interpretation of “Trouble Man” since Gaye’s 1972 original.

“Menacing” is le mot juste. Here, writing these lines, is one who previously thought he had exhausted the topic of Motown in two earlier TAC contributions. After almost a decade’s abstinence from the glories of Motown’s back-catalog, hearing this stuff live—at the hands of musicians mostly unborn in 1984, the year of Gaye’s death—can be quite a jolt. Age has not withered it, nor has custom managed to stale its almost infinite variety (how, by any canon of logic, could “Can I Get A Witness” have sprung from the same larynx as “Inner City Blues”?). That you might predict. Less readily expected is the sense of danger this music can still convey. As LaBonte and his colleagues demonstrated, even the 50th iteration of “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” cannot necessarily prepare you for the impact of the 51st.

One low point: the needless inclusion of “Abraham, Martin, and John,” a saccharine ballad that seems if anything more ill-judged in 2014 than it did when new. (Its lyrics optimistically maintain that the “John” of the title, alias JFK, “freed a lot of people”: whom, exactly? Cubans? Katangans? Cardinal Mindszenty, perhaps?)

But this is the evening’s sole concession to Doctor Feelgood. Elsewhere the excitement never relents; and as for the finale … well, if Woody Allen was right in crediting Wagner’s output with making you want to get up and invade Poland, then the Athenaeum’s concluding “Dancing in the Street” meltdown might well make you want to rebuild the Berlin Wall for the specific pleasure of newly demolishing it.

Talking of Teutonic communism, there might lurk a few unreconstructed T.W. Adorno groupies out there who long to denounce these musical delights as, shall we say, Entartete Kunst (any half-educated music-lover who has sat through YouTube footage of Goebbels’ rants finds it impossible thereafter to take seriously Adorno’s ethical pretensions, and difficult enough in all conscience to countenance E. Michael Jones’s efforts to put upon Adorno a Catholic spin). The Athenaeum’s audience—two-thirds of which, on this particular night, seemed to be under 35—could not have cared less about such bags of misery. A total, scandalized silence fell when LaBonte and Perl quoted the words of Gaye’s father and killer, words uttered by the horrid old man to his police interrogators:

POLICE OFFICER: Did you love your son?

GAYE SENIOR: Let’s say I didn’t dislike him.

Marvin Gaye, the Prince of Motown, had probably never once heard of Hilaire Belloc. But on leaving the Athenaeum, a Belloc epigram from 1909 acquired a new resonance: “It is the best of all trades, to make songs; and the second-best, to sing them.” At both trades, Gaye excelled. RIP.