Mark Twain Evades the Wokeness Trap

A new biography of the great American writer is fresh without being faddish.

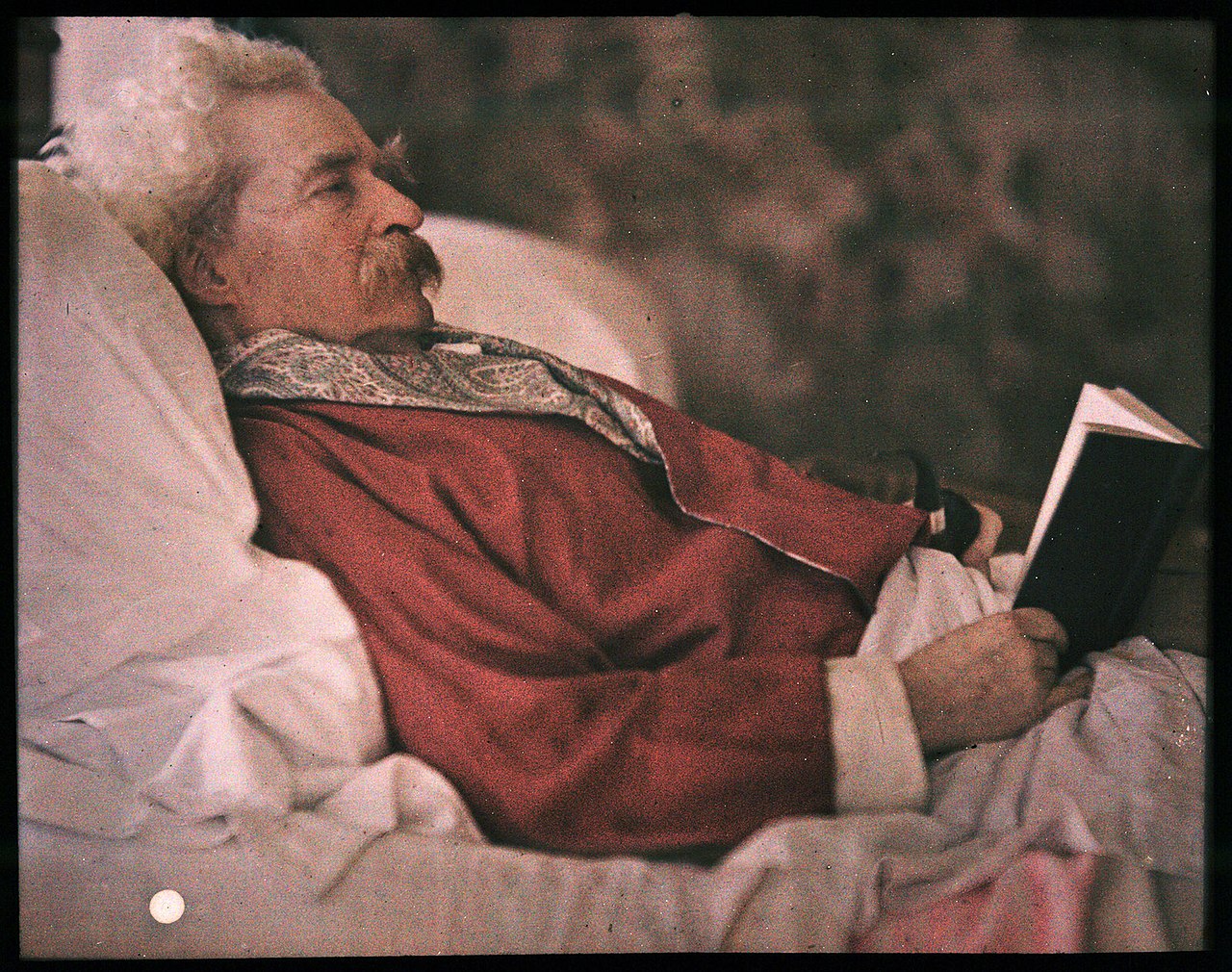

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow. Penguin Press, 1200 pages.

When I first became aware of the imminent publication of a new biography of Mark Twain, my first reaction was a sustained groan.

This was not because I harbored any ill will toward the celebrated American writer, whose legal name was Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Far from it: I had, from my earliest days as a precocious reader, held him in high esteem. In the English curriculum that I more or less created for myself, few books induced my admiration more than The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, or The Innocents Abroad.

Yet, in these dark days of our nation’s literary present, nothing is so ominous as the exhumation of the great artists from the past. So frequently have our cultural forbears been trotted out for woke reevaluation and reinterpretation that we rightly look with suspicion at purportedly fresh takes. Such was the cynical but not unwarranted attitude with which I embarked upon Ron Chernow’s Mark Twain. I turned the idea of this book over in my head: a biography of Mark Twain published in 2025. My mind raced with the myriad ways in which this venture could be corrupted or compromised by political correctness and cancel culture.

Twain not only bears the burden of having written about race in America, however insightfully or humanely, from the perspective of a 19th-century Missourian, but he has been the subject of innumerable previous biographical treatments—a bibliographical reality that presumably applies pressure on biographers to find new, as in woke, lines of attack. Yes, Chernow is a formidable figure—a Pulitzer Prize winner, an author of lives of Hamilton and Grant—but since when does a mainstream literary pedigree (let alone penning the inspiration for the musical Hamilton) guarantee immunity from wokeness?

It is with a measure of relief, if not shock, that I can report that Chernow has produced a literary biography of the first rank—serious, readable, not in thrall to the passing pieties and prejudices of our age. This Mark Twain is a genuine throwback. For the most part, Chernow has confidently and cheerfully navigated the landmines likely to be encountered by any contemporary chronicler of the author of Huck Finn.

In the opening pages, Chernow gently prepares the sensitive readers of the 21st century for the likelihood that, in the thousand-plus pages that follow, they will encounter a man whose attitudes, beliefs, and habits reflected his time—as well as his own inimitable personality, one far more peculiar than his popular image suggests. “Mark Twain has long been venerated as an emblem of Americana,” Chernow notes. “But far from being a soft-shoe, cracker-barrel philosopher, he was a waspish man of decided opinions. His wit was laced with vinegar, not oil.”

Getting to the heart of contemporary troubles with Twain, Chernow concedes that “our own heightened time of racial reckoning” makes Twain a tough case for both biographers and readers, but he declines to judge the author wholly by the standards of our time. “Born into a slave-owning family, he transcended his southern roots to a remarkable degree, shaking off most, but never all, of his boyhood racism. No other white American writer in the nineteenth century engaged so fully with the Black community or saw its culture as so central to our national experience,” Chernow writes.

Chernow readily admits other quirks of Twain’s character. “In many ways a Victorian man, he tended to place women on a pedestal and treated his wife with unfailing reverence,” writes Chernow, who proceeds to confront one of the most troubling aspects of Twain’s later life: his seeking, as a grandfatherly widower, friendships with teenage girls. “Like many geniuses, Twain had a large assortment of weird sides to his nature, and this account will try to make sense of his sometimes bizarre behavior towards girls and women,” Chernow writes. To his credit, Chernow neither flees from nor overstates his subject’s imperfections, oddities, and sins but aims to give an account of them. Chernow also does not use Twain’s personal flaws to undercut or erase his literary achievement—a sensible view that, in the present environment, seems almost revolutionary.

“To capture Mark Twain in his entirety, one must capture both the light and the shadow of a beloved humorist who could switch temper in a flash, changing from exhilarating joy to deep resentment,” he writes.

Having taken on the grand project of distilling his subject’s epic life in a single volume, Chernow helpfully breaks the book up into digestible units: Twain’s life is relayed, in strict but never plodding chronological order, over 69 short-ish chapters that encompass, among other things, his salad days in Hannibal, Missouri, his riverboat piloting career on the Mississippi, his extreme good fortune as a novelist and orator, his unceasing bad luck as a businessman, and his joy in the family life he created with his wife Olivia (“Livy”) and their three offspring who survived beyond childhood, Susy, Clara, and Jean—and his pain when the ranks of that family started to thin.

Chernow has in his favor not only an even-handed view of Twain but an actual ability to write—a gift that, in a literary environment in which jargon-heavy academic tomes are grossly overrepresented, is not to be taken for granted. Chernow writes expressively but clearly. When he produces a pleasing turn of phrase, he does so to elucidate rather than obfuscate—as in this description of Twain’s doomed financial support for James W. Paige’s typesetting machine: “For all his severe disenchantment with Paige, the machine still hypnotized Twain, like a failed love affair he couldn’t bear to renounce.” Chernow is equally felicitous in characterizing Twain’s best writing. Here’s how he describes a memorable passage from Tom Sawyer: “The visual clarity of the scene is worthy of a Winslow Homer painting of rustic boys at play on a summer day.”

But for the most part, Chernow doesn’t attempt to outshine the master. The nearest he comes to applying too thick a coat of his own elegance is when he describes Twain’s death in 1910: “He emitted a sigh and peacefully expired at age seventy-four, perhaps dreaming of being afloat on the biggest river of them all—eternity.”

Long before then, Chernow has demonstrated that he has come to terms with Twain—not uncritically, but empathetically. For example, only a biographer attuned to his subject could perceive the ways in which the notoriously irreverent, cynical Twain affected piety when seeking the hand in marriage of Livy. “When religion, coming from your lips & his, shall be distasteful to me, I shall be a lost man indeed,” Twain wrote to Livy, referring to his friend Joseph Twichell.

Among other things, Chernow is the beneficiary of the vast trove of Twain writings, including correspondence and notebooks available to underscore seemingly any topic or incident. We even hear Twain’s account to Livy of his feats of imagination when telling his daughters bedtime stories using the rather uninspired jumping-off point of an outline of a human figure that ran in Scribner’s Monthly: “I wore that poor outline devil’s romantic-possibilities entirely out before I got done with him. I drowned him, I hanged him, I pitted him against giants and genii, I adventured him all through fairy-land, I made him the sport of fiery dragons of the air and the pitiless monsters of field and flood, I fed him to the cannibals.” Chernow amply establishes how much Twain relished the company of his kith and kin.

Chernow’s capacity for comprehending Twain—for digging into his own mindset, however misguided—comes in handiest when he guides the reader through the more mystifying or bothersome aspects of his biography, including his indefatigable interest in establishing himself as a tycoon. “Now accustomed to ample living, he constantly searched for a windfall that would spring him from the demands of writing and lecturing, and offer him a leisurely, well-upholstered life,” Chernow writes, before noting his subject’s abject failure in the same: “With his extraordinary imagination, he readily magnified the commercial potential of any invention, losing any realistic sense of its true worth.” Besides the typesetting machine, Twain permitted his funds to be applied toward, among other things, a publishing house, inventions including a “Self-Pasting Scrap Book,” and, perhaps most unbelievably, a “miracle substance” that had been developed to relieve dyspepsia, Plasmon. The last, at least, was borne of a genuine ailment that Twain lamented in print: “Indigestion hath the power / to mar the soul’s serenest hour.” As Chernow explains in another context, “An enthusiast by nature, Twain, once he had latched on to an idea, could not let it go.”

Twain’s financial straits, which compelled him to abandon his costly homestead in Connecticut, accept international speaking engagements with the promise of ample remuneration, and file for bankruptcy, loom over the book. “Our outgo has increased in the past 8 months until our expenses are now 125 per cent greater than our income,” Twain told his brood at one low point, and although his arithmetic was apparently off, the author takes this admission as a chance to further explicate his subject’s mindset: “It showed how scarred he had been by bankruptcy and how much he still feared the poorhouse.”

As for Twain’s apparently chaste but nonetheless inexplicable and inappropriate friendships with the teenage girls he dubbed “angelfish,” Chernow proposes that this bizarre behavior could have been a manifestation of his profound woe following the deaths of Livy and their eldest daughter, Susy: “Twain now suffered from extreme loneliness and despondency and the angelfish filled the large void left by Livy’s death, giving him a chance to create a happy new family”—one of several theories proffered, none exculpatory. Chernow tries to sort out Twain’s tortured psychology but he never excuses Twain’s weirdness, which is fully on display in his correspondence with these girls—the excerpts from which are truly cringe-inducing. “The letters all have the same cloying, affectionate ring,” Chernow writes, here stating the obvious in a characteristically fair and measured tone.

Chernow mounts a nuanced defense of Huck Finn, including its representation of the escaped slave, Jim. “Whatever the shortcomings of Twain’s presentation of Jim, the Black man emerges as the morally superior figure in the story, surrounded by an appalling menagerie of whites who cheat, scheme, lie and kill,” Chernow writes. Arguing that the book’s inclusion of the “n-word” renders it a legitimate challenge when presented to students, Chernow proposes that Huck Finn “may be ... better reserved for higher education or else studied in conjunction with other contemporary works about slavery and abolitionism”—a reasonable enough position.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

The heartiest compliment I can pay to Chernow is that at no point did I wish, as I first suspected I might, that I was reading a book by Twain instead of one about him. Chernow wisely forestalls such a reaction by including so much of Twain in his own words. We have an account of Twain, lobbying for copyright extensions that would benefit his heirs financially, stopping by Theodore Roosevelt’s White House and telling the doorkeeper: “I want the usual thing. I’d like to see the President.” We have selections from a speech he gave in 1882 on “Advice to Youth,” including the following guidance: “If a person offends you, and you are in doubt as to whether it was intentional or not, do not resort to extreme measure; simply watch your chance and hit him with a brick.”

And we have his view of physicians—so skeptical that he allowed himself to be sweet-talked by “mental science” practitioners (even though he disdained Mary Baker Eddy’s Christian Science): “The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d druther not.” A further wrinkle in Twain’s firm irreligiosity is the high esteem with which he held his novel about Joan of Arc—also his daughters’ favorite: “When he read aloud from it, Susy would jump up and say, ‘Wait, wait till I get a handkerchief,’” Chernow writes. “Surrounded by such rapt listeners, Twain was not likely to question his idealized portrait of the Maid of Orleans.”

There are many ways to mark the gradual decline of wokeism in our society, but I myself did not believe that that pernicious habit of mind was on the wane until I read a biography of Mark Twain that sought neither to commend nor condemn him—but merely, humbly, to grasp him in full.