How This Neoconservative Found the Catholic Church

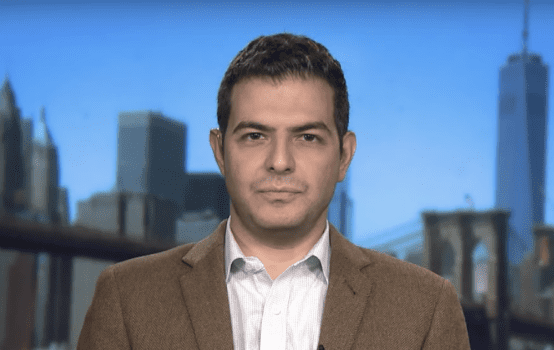

From Fire by Water: My Journey to the Catholic Faith, Sohrab Ahmari, Ignatius Press, 240 pages

There is a famous Persian proverb, Sokuni be-dast ar ey by sabât, ke bar sang-e ġaltân na-ruyad nabât, which translates to something close to “a rolling stone gathers no moss.” As a conservative and traditionalist Catholic, I find that sentiment quite appealing and true to life. Yet there are exceptions, among them the Iranian-American Sohrab Ahmari. The popular writer at Commentary and former editorialist at The Wall Street Journal has rolled quite quickly in his relatively short life, from Shia Islam to Nietzschean nihilism, from Marxism to neoconservativism. Now, in his spiritual biography, From Fire by Water, Ahmari charts his intellectual travels into Catholicism, to which he converted in 2016. For the reading list alone, Ahmari’s apologia is a valuable resource for understanding the intellectual evolution of the West and how traditional religious belief still offers the best answers to man’s quest for truth.

Ahmari was born into a middle-class family in Tehran several years after the 1979 revolution. Many members of his family, including his father and mother, were more aesthetes than pious Muslims. All the same, much of his upbringing—especially that which occurred in the country’s public school system—was set in the larger context of the aggressive Shiism of post-revolution Iran. Yet Ahmari developed a cynicism towards Islam reminiscent of his bohemian father, who drank alcohol and watched Western movies behind closed doors. Of Iran, Ahmari writes, “when it wasn’t burning with ideological rage, it mainly offered mournful nostalgia. Those were its default modes, rage and nostalgia. I desired something more.”

As he grew older, Ahmari’s concerns with Islam increasingly focused on its antagonism towards free will and reason. He explains: “My turn away from God had something to do as well with the nature of the Islam of Khomeini and his followers, a religion that never proposes but only imposes, and that by the sword or the suicide bomber…. In broad swaths of the Islamic world, the religion of Muhammad is synonymous with law and political dominion without love or mercy…. There is little room for the individual conscience and free will, for the human heart, for reason and intellect.”

Indeed, as I’ve noted in two recent articles on Islam, the dominant streams of the religion have always had difficulty reconciling their beliefs—and certainly the nature and development of the Quran—with public rational discourse or academic scholarship. If one considers a map of the world where apostasy laws are in effect, it largely matches where Islam is the dominant religion. Radical Islamism as a distortion of a peaceable, rational Islam, Ahmari writes, is “little more than a polite myth.”

After Ahmari’s parents divorced, he and his mother immigrated to Utah when he was 13 years old. It was quite the culture shock—in part because he found many Americans far less intellectually curious and far more conformist than he had imagined, but also because it involved shifting from the Persian bourgeoisie to living in a trailer park. As an Iranian in a part of the country that was predominantly white, it was always going to be an uphill battle to be socially accepted. But Ahmari’s fervent intellectualism added to this isolation. Though this was also perhaps a blessing in disguise, as he began devouring the kinds of books most Americans know they should read but never do. “Reading the great books in one’s late teens is intoxicating,” he observes.

First on his list was Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which he consumed in a few days, barely stopping to eat or groom himself. Ahmari identified with the ubermensch, or “superman,” who exemplifies the evolutionary peak of the human person, defined by self-mastery, radical creativity, and an intense cynicism towards absolute morality. Though it would take a few years, Ahmari eventually came to see the errors of the German philosopher. “Today I consider most of Nietzsche’s ideas to be not merely wrong but positively sinister,” he says. All the same, as I’ve argued elsewhere at TAC, Nietzsche’s philosophy is at play across American culture, education, and politics. References to “empowerment,” to redefining morality according to man’s own needs (or whims), and to accomplishing our goals through force of will are all to varying degrees tinged with Nietzsche’s influence. It’s important that we be exposed to him and his ideas, even if he is deadly wrong.

The next major influence on the young thinker were existentialist writers (and communist sympathizers) Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. For Ahmari, this was a logical progression from Nietzsche, who “considered man to be his own moral measure, and…licensed an elite to designate new values and overthrow the old.” This was exactly what Marxism offered. “By the age of eighteen, I was quite literally a card-carrying Communist,” he writes. Ahmari fervently embraced the ideas of dialectical materialism, class struggle, and anti-capitalism. But, he acknowledges, “Marxism’s greatest attraction was its religious spirit,” its emphasis on a secular salvation, revolutionary justice that “would wipe away every tear.” Again, like Nietzsche, Americans need not embrace Sartre or Marx to see the need to read and understand them—especially when Marxism is such a dominant force at most U.S. universities. One must understand the best attacks on conservatism and religious belief in order to defend them.

Anyone familiar with the philosophical traditions influencing the American academy can probably guess what came after Marx for the young Ahmari: Jean-Francois Lyotard and Michel Foucault, the deconstructionists who tackle topics like “sex and gender, language and the unconscious, colonialism and postcolonialism, media and pop culture.” At this point, Ahmari defines his worldview as the following: “Man’s place in the world is unsettled; he is homeless. Capitalism’s pitiless destruction of older social forms, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, Freud’s discovery of the unconscious—all these things had made it impossible to cling to any eternal or permanent truth about humanity…. Everything about people turned on historical conditions and social power dynamics.” According to these thinkers, man is repressed by society, which can be reduced to performative “language games.”

Yet Ahmari recognizes now that postmodernism’s analysis means there is “no standard left on which to base these various claims for justice.” It would take a number of life experiences, including two years doing Teach for America (TFA), to help Ahmari see the errors of his ways. While he halfheartedly sought to impress his Marxism and relativism on his students, another teacher imposed strict rules and procedures to guide learning. The latter had far more success. As Ahmari writes, “good teaching [is] at heart about order—order, in the teacher’s mind, about the lesson he was going to impart on a given day; order in the minds of students, who needed routine, regularity, and predictability from adults; and order in the sense that peace reigned in the classroom and those who disturbed it knew what to expect.” The TFA experience also convinced Ahmari of a fatal flaw in leftist ideology—people aren’t reducible to “language, race, class, and collective identities.” Anyone, and everyone, regardless of circumstances, can choose to be virtuous, to cultivate the good in themselves and society.

It was around this time that Ahmari began reading anti-communist literature that helped persuade him that rather than being an oppressor, the kinds of absolute moral laws propagated by the Judeo-Christian tradition were actually “a bulwark against totalitarianism.” He adds: “The God who revealed himself in the moral law, and who condescended to be scourged and crucified by his creation—this God was a liberator.” In time, he came to recognize that the most praiseworthy elements of Western civilization cannot be understood apart from the religious traditions that brought them into being. These traditions view man as having inherent dignity and possessing certain inalienable rights. Thus did Ahmari begin to “make peace with American society,” and develop into a popular neoconservative writer.

Soon he was reading the likes of political theorist Leo Strauss, biblical scholar Robert Altar, popular Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, the Church Father Augustine, great Catholic convert John Henry Newman, and the great scholar/theologian/pope Joseph Ratzinger. Ahmari is not the only one whose reading of Augustine led him into the Church—Washington Post columnist Elizabeth Bruenig trod a similar path. But perhaps what’s most consistent amid Ahmari’s intellectual journey from Islam through various forms of post-Enlightenment ideology and ultimately into Catholicism is his search not only for truth but freedom. It was the deeper, more authentic vision of freedom in Christianity that spurred Ahmari towards a greater conception of the world and the human person. “True freedom, Benedict [XVI] taught, was something else. It was ‘freedom in the service of the good,’ freedom that allowed ‘itself to be led by the Spirit of God.’”

It is this same search for freedom that underpins the conservative project to which Ahmari now contributes—albeit, to my chagrin, of a more neoconservative variety. Yet any conservatism that perceives man’s flourishing as intimately linked to his creator is one worth lauding.

Casey Chalk is a student at the Notre Dame Graduate School of Theology at Christendom College. He covers religion and other issues for TAC.