Hobbes With a Halo

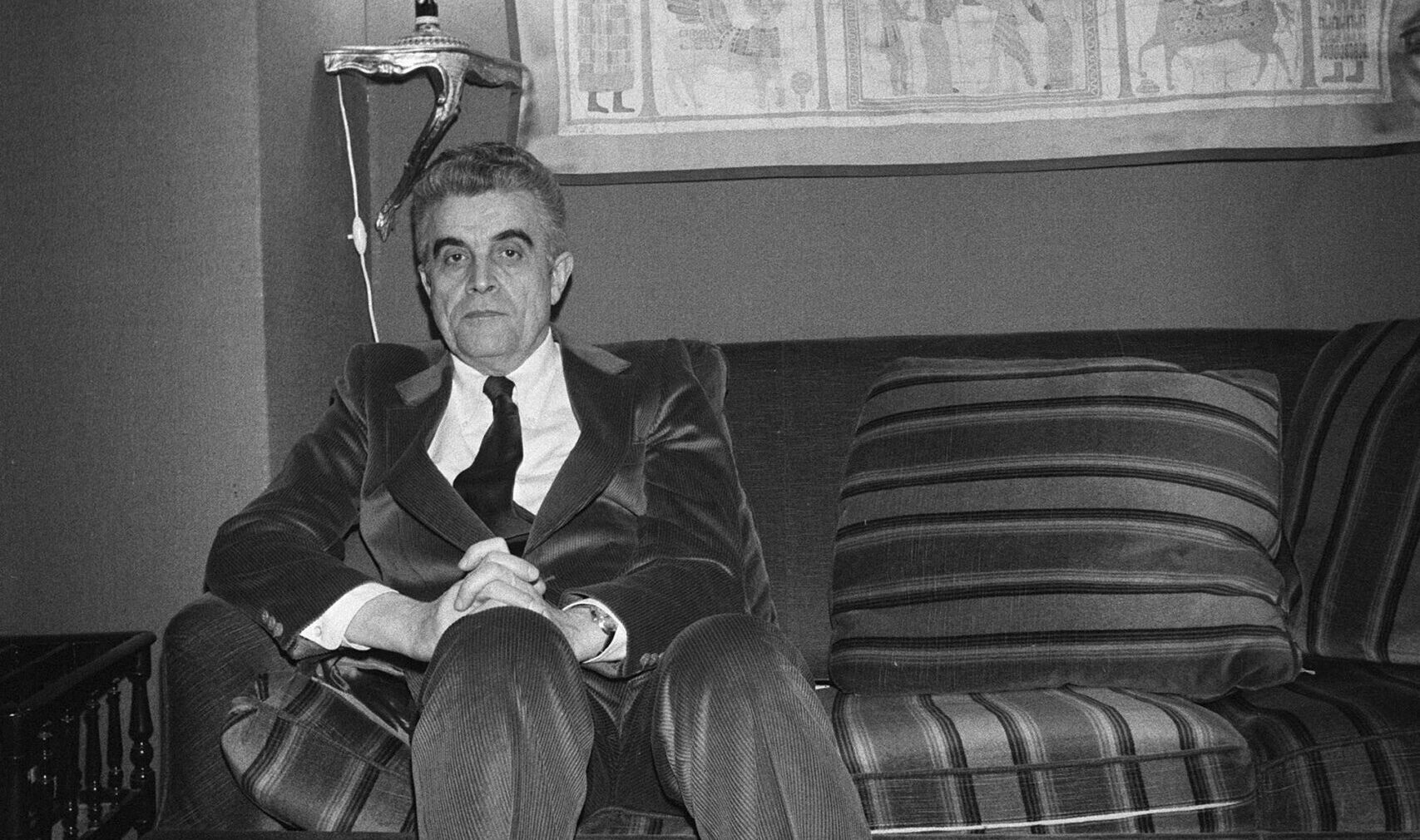

On the magnetism of the life and ideas of René Girard.

I Came to Cast Fire: An Introduction to René Girard

by Elias Carr

Word on Fire, 160 pages, $24.95

Mystery cults that formed around émigré professors in postwar America are sometimes accused of influencing politics, even as we leave the 20th century far behind. On the left, “cultural Marxist” expatriates associated with the Frankfurt School, especially Herbert Marcuse, allegedly invented identity politics. On the right, the students of Leo Strauss, another refugee from the Third Reich, supposedly masterminded the Iraq War. Perhaps less well-known but more indirectly influential is René Girard, whose lectures about desire at Stanford University in the 1980s convinced Peter Thiel to invest in Facebook during the infancy of social media. Among these postwar émigré-professor scapegoats for our 21st-century problems, Girard is most like the classic cult leader who gathers disciples around a single apocalyptic insight. He also has much to say about scapegoating.

Readers curious about Girard’s life should watch the 2024 documentary Things Hidden, available for free online, which explores how he develops his idée fixe that humans are copycats when it comes to who we want to be. The development of this idea—mimetic desire—takes place in three stages that correspond to three major books that he wrote in the 1960s and 1970s. First, tasked with teaching literature at Bryn Mawr College in the 1950s, Girard notices how the heroes of Don Quixote, The Eternal Husband, and The Red and the Black all eventually realize that their imitation of literary role models has brought them to ruin. His book Deceit, Desire, and the Novel proposes that Cervantes, Dostoevsky, and Stendhal teach readers that desire is “mimetic.” Don Quixote realizes he has vainly and foolishly imitated the long-dead heroes of chivalric romance. Living role models, however, set the stage for rivalry and conflict, as when Julien Sorel’s social-climbing aspirations turn violently against Madame de Rênal. Second, in a moment of insight on a train between Bryn Mawr and Johns Hopkins, it occurs to Girard that “mimetic” conflicts explain the origins of human culture and the pervasiveness of sacrifice across archaic religions. Delving into speculative deep history, Girard’s Violence and the Sacred argues that mimetic violence must have spiraled out of control among our hominid ancestors till they united against a single scapegoat, whose murder would end the war of all against all, at least temporarily. Sacrifice ritualizes this scapegoat mechanism. Religious violence, therefore, is the unstable core of social order that allows primitive communities to survive mimetic violence. Girard’s trespasses from literary theory into anthropology and sociology were warmly received by the sort of Paris intellectuals who already admired Georges Bataille’s exposé of the role of irrational sacrifice in human community. But then, third, Girard eventually comes forth with an apologetic flipside of his big insight. From Abel to Christ, the Bible and Christianity reveal that God takes the part of the victim, giving the lie to all other religions, and exposing the violent core of human cultures. His book Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World outs Girard as a Christian apologist rather than a fashionable atheist critic of religion tout court.

The double conclusion of Girard’s single insight—mimetic violence binds all human communities except the Christian—makes him a polarizing figure. Footage in Things Hidden shows laïc Frenchmen on TV in the late 1970s discovering, to their horror, that Girard’s critique of violent religion doubles as an apologia for Christianity. But Girard’s insight is strange and off-putting to Christians, too, at the same time. J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, the most widely read midcentury Christian public intellectuals and novelists, find much more than violence in ancient pagan myths. Postwar revivals of Thomism by Étienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain, meanwhile, identify reason and the common good, not irrational desire and violence, as the foundation of human political communities. And Romano Guardini and Josef Pieper insist that humans are not only desiring machines, but creatures open to transcendence. Girard’s fixations leave room neither for primeval wonder nor public reason. In contrast to mid-century Christian rediscoveries of reenchantment, rational consensus, and the receptive dimension of human beings, Girard paints a dark picture of ancient cultures, political forces, and human nature. He appears on the scene like Thomas Hobbes with a halo.

Fr. Elias Carr’s I Came to Cast Fire: An Introduction to René Girard begins with hagiography. Girard is introduced as a first-rank French thinker from the start, a peer of Jacques Derrida. Yet this scholar whom Michel Serres called “a new Darwin of the human sciences” and whom Roberto Calasso called “the last Father of the Church” needs no more adulation. Cynthia Haven’s biography The Evolution of Desire, though no less appreciative of Girard in the end, offers a more true-to-life portrait of an autodidactic snob and late bloomer. Qualified to teach French literature in America only by dint of being French, Girard rederives a critique of amour propre, the vain desire for esteem in others’ eyes, that was already shopworn in 1755 when Rousseau borrowed it from Pascal and La Rochefoucauld. Yet without an education to diminish his confidence in his originality, Girard doggedly extends his insight about mimetic desire to explain the near-universality of sacrifice in archaic religion. Relative isolation and naïveté better account for Girard’s tenacity in extending his ideas to anthropology and scriptural interpretation. The result is an astonishing, original, and significant breakthrough insight about the prevalence of sacrifice across archaic religions. (Certainly Freudian kookiness about reenacting the murder of the father is no better explanation!) For Calasso, this sort of stubborn genius makes Girard the ultimate “hedgehog” in the field of intellectual history: He understands the whole world through the lens of one single defining idea.

I Came to Cast Fire is an introduction to Girard’s ideas, not to his life.. While Luke Burgis’s Wanting is still the best layman’s orientation for a practical grasp of mimetic theory for everyday life and business, Carr offers more for those who are ready to go deeper into Girardian ideas. The book builds one lucid explanation of Girard’s concepts and terms upon another—katēchon, mediation, scandal, transference—illustrated by personal stories and examples. A handy glossary and guide for further reading comes at the end. Graphical representations of the “triangularity” of mimetic desire make vexing “clarifications” unnecessary, such as the crucial point for Girard that have-nots do not desire what havers have, but rather to be what havers seem to be because they have what they have. (Now, don’t you want the chart?) Moreover, the book is attentive to theological implications of Girard’s ideas, such as whether Satan is naturalized into mimetic violence. (Maybe not, Carr crosses his fingers.) Carr is a student of the late Raymund Schwager, S.J., the priest who co-founded the Colloquium on Violence and Religion, the main proselytizing arm of the mystery cult, with Girard in 1990. This makes him an adept guide to the subtler ways that Girard makes his peace with Catholic Christianity as a sacrificial religion throughout the 1990s.

What one does not find in the book, nevertheless, is a defense of Girard from some obvious objections, including Christian ones. Strangely for a Catholic thinker, Girard brackets the fundamental questions whether desire alone is fundamental to human beings, and whether desire is separate from knowledge. Modern philosophers like Hobbes and Spinoza bracket these questions, as I understand them, to head off the possibilities that human beings are created to receive the grace of God on the one hand, or that Christian love somehow illuminates truths about persons on the other. But the same anti-Christian motives cannot settle Girard’s mind against the mysterious operations of divine grace. In the end, Carr argues that Girard must postulate a superior power to mimetic desire: that of the Holy Spirit. Oddly, however, Girard continues to insist that, although the Holy Spirit predates the production of the sacred through mimetic violence, he has nothing to do with mythic religion or secular politics until he came to inspire Christians to live according to Christ’s model counter-myth at Pentecost in 33 AD. Up to this point, Girard remains inside a mechanistic account of human desire that would be familiar to early-modern philosophers bent on debunking ancient wonder. Are extra-Biblical myths and histories merely the chronicles of sin and its effects upon the world, devoid of any mysterious traces of the holy and human longings for it? If we are permitted to doubt this, then Girard’s mimetic theory is like a powerful light that casts everything else into shadow.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Even if Girard’s single, dense insight does not tempt one to abandon a richer banquet of Christian thinkers and other philosophers for his mystery cult, he does deserve to be seen as a latter-day Father of the Church, with an important place at a bigger table. In The City of God against the Pagans, Augustine criticizes Rome for being thoroughly corrupted by the lust for domination from the very beginning. This social critique succeeds too well. It contravenes Augustine’s ostensible purpose, which is to convince public-spirited imperials from Rufus Volusianus to Edward Gibbon that the Bible and Christianity provide better foundations for a just and stable political order. If humans are so deeply enslaved by original sin, and if kingdoms are nothing but great bands of robbers, why bother defending any political goods? Many an “Augustinian” critique has disillusioned Christians who might otherwise defend the goodness of natural religion, natural reason, and the common good. Girard belongs to a long Gallic tradition of such Augustinians, from the Jansenists to Jacques Ellul, who oscillate between radical social critique and a political quietism that cleaves to the perfect example of Christ alone. His powerful insight challenges us to think seriously about how sin, or mimetic desire, wreaks havoc in everything from our everyday lives to geopolitical events. If Thiel is correct that Girard awaits recognition as the thinker of our time, then ours are dark times.

Girard is most attractive to Christians who expect to find a smart critique of the problems of modernity within scripture and tradition. Carr is no exception to this. He describes being transfixed as a young Catholic priest in Northern Virginia by I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. In this book, Girard argues that after Christianity exposes the scapegoat mechanism, modern ideologies must mask their violence in the same concerns for victims. Modernity is not a post-Christian but a hyper-Christian “planetary” culture that lacks any safeguards once it abandons the model of Christ. Mimetic violence breaks out against competing savior complexes—nationalisms, socialisms, even anti-totalitarianisms—that claim to speak for victims. How enviable are the leaders who make the world a better place; how easy it is to reduce our rivals in this domain to detested political labels. Perhaps Girard understands the violent derangement of people who politicize every innocuous conversation and social gathering. Carr points out that, having died in 2015, Girard did not live to see these trends manifest in the recent peak of “cancel culture.”

Carr’s book is an accessible introduction to Girard’s powerful ideas, including for those of us who remain wary of turning Christianity into the all-or-nothing counter-myth that is our only bulwark against an all-too-human apocalypse. In Girard’s last book, Battling to the End, globalization and communication technology bring our models and rivals ever closer, so that humanity spirals towards the ultimate mimetic crisis of nuclear war. This overheated end-times jeremiad seems perfect for the pulpit; the Girardian can criticize mimetic conflicts only from a self-flagellating position that confesses his own sinful desires. While Girard may satisfy the priest more than the professor, he does have a message about the human heart that one should hear every week, according to the third commandment of my own pedestrian mystery cult.