Good Night, and Good Luck—Lots of It

If Broadway’s latest is the focus of resistance to Trump, the president can rest easy.

The great Broadway lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, oft accused of advancing sentimental notions in such shows as Oklahoma! and The Sound of Music, once said, “In my book, there’s nothing wrong with sentiment, because the things we’re sentimental about are the fundamental things in life: the birth of a child, the death of a child, or anybody falling in love.”

Excluded from this litany of appropriate objects of sentimentality: journalists and actors impersonating journalists on screen or stage.

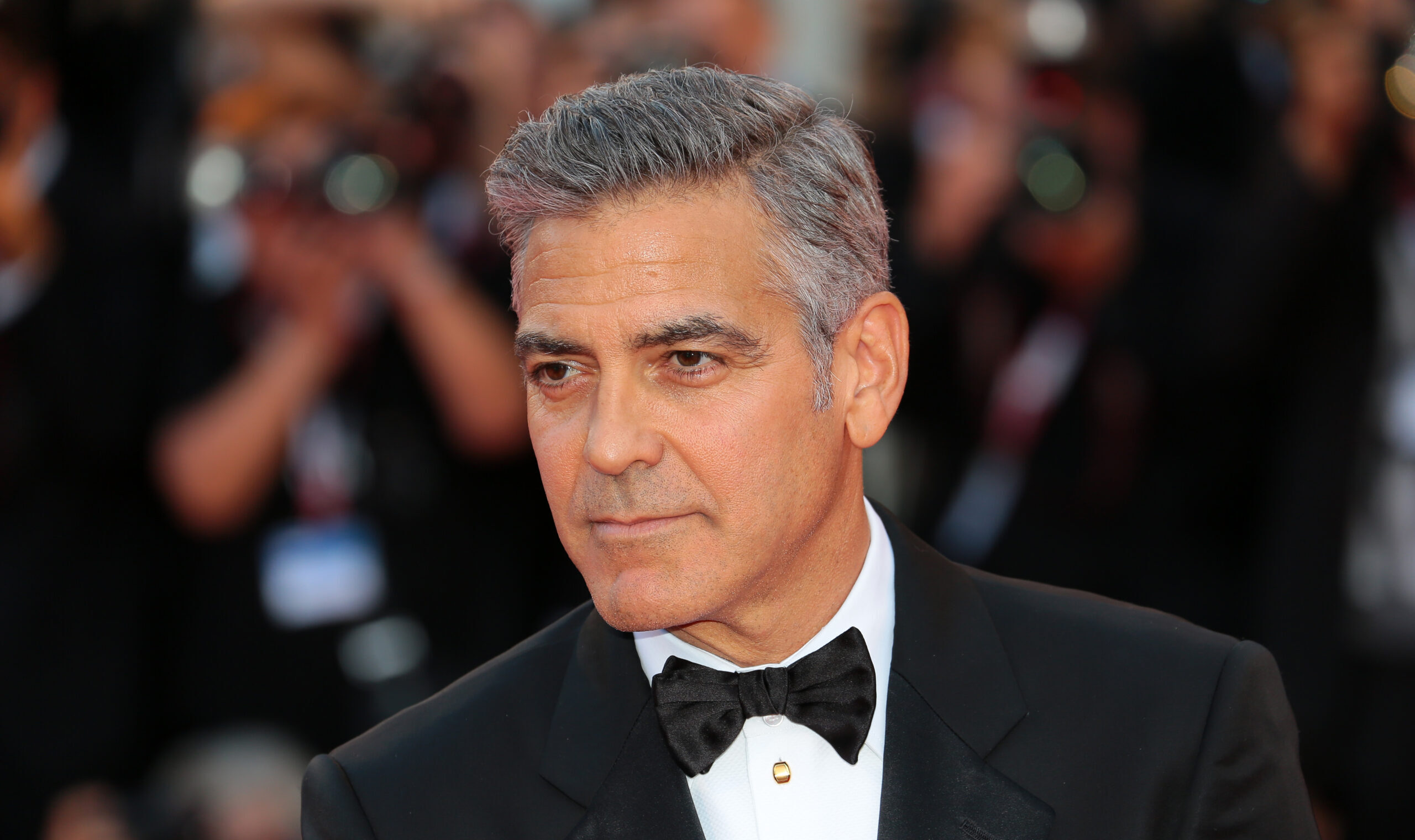

George Clooney did not get the memo. Twenty years ago, Clooney wrote, directed, and costarred in Good Night, and Good Luck, which attempted to wring an inspiring moral fable out of the televised acrimony between CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow (played, in the film, by David Strathairn) and anticommunist Senator Joseph R. McCarthy (seen in news clips and thus, technically, played by himself). Clooney could have titled the movie The Demigod vs. the Demagogue.

But now Clooney has brought his hero-worship to Hammerstein’s own Broadway. That songwriter may have waxed poetic about whiskers on kittens and such, but he could never have produced a work as sloppily mawkish as the stage version of Good Night, and Good Luck, which opened at the Winter Garden Theatre in March and a performance of which was broadcast live on Saturday night on CNN. (I have not seen the show on Broadway, but I did draw the unfortunate assignment of watching the broadcast gavel-to-gavel.)

In one sense, it was almost inevitable that Good Night, and Good Luck would eventually wend its way to TV: a script purporting to celebrate the special solemn mandate of television news would, naturally, be attractive to television news channels, especially those, like CNN, that have acquired a reputation for self-referential self-righteousness.

Indeed, the signaling of virtue was the pervasive theme of the evening. The inhabitants of our divided nation can seldom agree on anything, but the actors on the stage, the ticket-buyers at the Winter Garden, and the CNN hosts presiding over pre- and post-play coverage were all, blissfully, on the same page. Since he made the movie during the Bush administration, Clooney undoubtedly had different metaphorical targets in mind when he first found dramatic potential in the Murrow–McCarthy televised tiff. This time, however, Clooney’s only goal is to draw an equivalency between McCarthy and Trump—and, even more improbably, between Murrow and himself.

For those of us who dissent from Clooney’s metaphors, though, this latest iteration of Good Night, and Good Luck was tough going. Truth to tell, the original movie version was not altogether horrible: Despite its many insufferable qualities, it was well-photographed (in black-and-white) and generally well-acted, especially by Strathairn as Murrow. For the Broadway version, however, Clooney has taken up the role of the newsman himself. This seems less a concession to the commercial realities of Broadway than to the ego of Clooney: After all, since making the movie two decades ago, Clooney has cottoned to the idea that he is not merely a well-compensated screen actor but a Democratic Party power-broker capable of meaningfully contributing to the dislodging of his party’s presidential candidate.

On the basis of the CNN broadcast, the switch from Strathairn to Clooney had no upside whatsoever. With his lacquered jet-black hair, Clooney adopted something like the look of Murrow, but his attempt to imitate his voice was hilariously misguided: When speaking to his various colleagues and higher-ups at CBS, Clooney-as-Murrow adopted an approximation of his normal speaking voice, but when addressing the camera on the Murrow-hosted See It Now, the actor used a clipped, weirdly high-pitched tone that less suggested a midcentury news icon than one of the title characters on Alvin and the Chipmunks. The rest of the cast is burdened with the inevitable drabness of a televised play: Without the benefit of the tools of cinema, like editing, underscoring, and changes in scenery, they are left with words—many, many words, though all on the same theme: Murrow stands for all that is good and right, and McCarthy is evil without subtlety or shading. Clooney’s conception of the role of the news media is entirely one of confrontation: Murrow, far from being a neutral deliverer of “the news,” is lionized only because he openly went on the attack against McCarthy.

But this sort of critique implies that the crowd at the Winter Garden wanted actual entertainment. In fact, I contend, the play has been revived simply as a vessel for its intended audience’s favorite emotion, Trump hatred. This was proven by the timing and intensity of the applause heard throughout the broadcast. When a character sadly noted that “all the reasonable people took a plane to Europe and left us behind,” the audience, evidently embarrassed by the way their friends on the continent view their nation, responded with great expressions of sympathy, and when Murrow angrily denounced McCarthy, the crowd cheered with the same effusiveness they presumably show when Rachel Maddow excoriates Trump.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Those with a sense of irony, or history rhyming in unlikely ways, need not bother. During one of his on-air screeds against McCarthy, Clooney-as-Murrow made reference to the “junior senator” having blurred “the line between investigating and persecuting”—an obvious crowd-pleasing line, even though this particular crowd was unlikely to be attuned to the reality that it is none other than Donald Trump who could most credibly claim to be a victim of such blurring of investigation and persecution.

A year ago, Clooney reckoned he was saving democracy by pushing Biden to the side; now, he seems to think he can swoop in to save television, which, by his reckoning, has been in decline ever since the purported high point of the Murrow–McCarthy row. Throughout the play, Milton Berle is spoken of with derision for being the most trusted man in America, and, in a pretentious, tendentious closing montage of various highlights and lowlights from the past 60-some years of American broadcasting, is thus weirdly made to seem to anticipate Jerry Springer, the O.J. Simpson freeway car chase, and the January 6 riot (clips of which are shown). We get it, we get it—Saint Murrow would be displeased.

After the conclusion of the spectacle, CNN’s Anderson Cooper returned to remind those still watching that the preceding presentation represented “the first time a Broadway play has been broadcast live around the world.” In so doing, Cooper inadvertently made a case for Trump’s attempts to defund PBS, which, historically, has shown stage shows on programs like Great Performances. Who needs public broadcasting when we have George Clooney?