Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule: Leviathan’s Apologists

One of the tenets of the Progressive movement, the progenitor of the New Deal, was that technical “experts” are better equipped to solve social problems and market failures than elected officials or ordinary citizens acting on their own. Hence the advent, over a century ago, of regulatory agencies charged with implementing vague laws that confer sweeping powers upon unelected bureaucrats.

“Administration” by elites informed by science was heralded as an improvement over, and even a substitute for, the outdated framework of representative self-government. The Interstate Commerce Commission (1887), the Food and Drug Administration (1906), and the Federal Trade Commission (1914) eventually begat the alphabet soup of federal agencies that comprise the modern administrative state. Unaccountable government bureaucrats now wield extraordinary power, including the promulgation of a bewildering array of administrative regulations that dwarfs Congress’s lawmaking in volume and complexity.

Another Progressive tenet, famously advanced by President Woodrow Wilson, is that the U.S. Constitution is an obsolete impediment to the administrative state. In particular, Progressives regarded the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, and limitations on Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce, as antiquated features needing to be revised or ignored. Wilson’s sentiments ultimately carried the day, not by constitutional amendment, but through a gradual process of acquiescence and dereliction. Congress delegated considerable lawmaking power to executive branch agencies; the Supreme Court abdicated judicial review over many agency decisions; and now the de facto fourth branch of government, the bureaucracy, often answers to no one, not even the president.

Many Americans and most conservatives view these developments with growing alarm. They derisively refer to the bloated administrative state as “the Swamp.” In recent years, some mostly right-of-center scholars—notably Philip Hamburger, Richard Epstein, Gary Lawson, Peter Wallison, and John Marini—have written devastating critiques of the administrative state, including challenges to the legality and constitutionality of administrative law itself.

Not all scholars share the critics’ desire to drain the Swamp. In Law & Leviathan, Harvard Law School professors Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule—an odd pairing of, respectively, an Obama administration veteran and a former Scalia clerk who espouses a substitute for originalism that he terms “common-good constitutionalism”—undertake a breezy defense of the status quo, while recommending a few minor tweaks in lieu of dramatic changes.

Both scholars teach administrative law, and their slim book (145 pages of text) evinces an insider’s familiarity with technical minutiae in a field where such minutiae abound. Both authors are significantly invested in preserving the overall model of administrative law as it has emerged since the enactment of the Administrative Procedure Act in 1946. This administrative law orthodoxy is deeply entrenched in the legal academy. As Michael Greve observed in a review of Vermeule’s 2016 book, Law’s Abnegation, “administrative law’s arc toward deference simply marks the triumph of a certain legal class.” The book is obviously directed at this sympathetic audience.

To their credit, the voluble authors do not pretend to be dispassionate. Both have previously written in favor of (in their words) “broad discretion for the administrative state.” Modern problems are complex and require agency expertise “in the service of the general welfare.” This perfectly summarizes the smug sentiment underlying Progressive thinking: citizens are incapable of taking care of themselves without the assistance of an enlightened cadre of highly educated technocrats.

♦♦♦

The administrative state appeals to the elite class because it enables them to exert control over the rest of society without the nuisance of elections or consumer choice. Sunstein and Vermeule undoubtedly fancy themselves as latter day versions of Rexford Tugwell and Adolph Berle, who as members of FDR’s “Brain Trust” helped him design and implement the New Deal. “Trust us,” their tone suggests, “We’re experts.” Administrative law is “something to celebrate,” they conclude. Americans “should be grateful” for it. According to Ivy League technocrats, only an ingrate would oppose the Swamp.

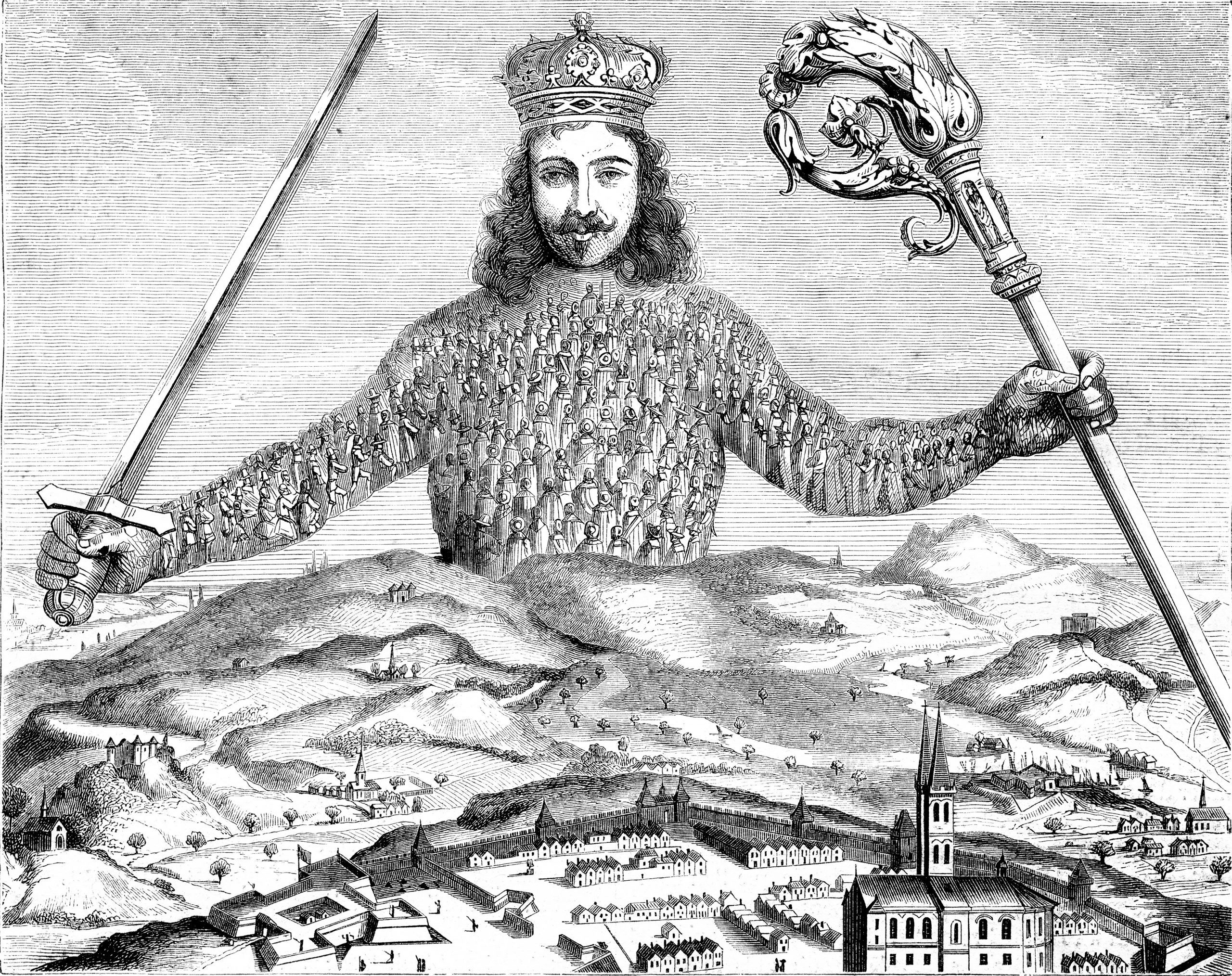

After acknowledging that critics of the administrative state “are no monolith,” Sunstein and Vermeule unaccountably lump them together and flippantly label them “the New Coke,” ostensibly referring to them as disciples of Chief Justice Edward Coke, the 17th century common law judge who opposed Stuart despotism, while also snidely invoking the soft drink blunder of the 1980s. As Columbia law professor Philip Hamburger documented at length in his 2014 book, Is Administrative Law Unlawful?, Coke opposed power-hungry kings like James I who used the notorious Star Chamber to advance the Crown’s agenda by issuing lawless diktats. Lawmaking by unelected agency bureaucrats is just as arbitrary as unilateral edicts of a monarch. Mocking Hamburger’s trenchant analysis as “the New Coke” is condescending and supercilious.

Sunstein and Vermeule facilely trot out the standard justifications for the administrative state: Congress authorized it; circumstances require it; the Constitution allows it. The first point is, unfortunately, true. But that begs the question whether the Constitution allows Congress to delegate its lawmaking power. Critics contend not, and some urge the resuscitation of the once robust “nondelegation doctrine.”

The second point accepts the policy premises of the New Deal and brushes aside constitutional objections to FDR’s radical expansion of the federal role. Sunstein and Vermeule repeat the Progressive mantra that the administrative state is “in some sense mandatory” to realize the goals of a paternalistic, redistributionist welfare state. This amounts to saying “You have to break a few eggs to make an omelet,” which again begs the question whether the Constitution allows those eggs to be broken.

The last point deserves a more detailed review than the cursory treatment it receives in Law & Leviathan. Sunstein and Vermeule begin by charging that critics of the administrative state are “best understood as a living-constitutionalist movement,” falsely suggesting that “the New Coke” is unsupported by constitutional text and history. Sunstein and Vermeule then erect a straw man, characterizing the critics’ “main concern” as “the overriding fear that the executive will abuse its power.”

This is incorrect. The critics’ main concern (keeping in mind that they speak with many voices) is that the administrative state violates the constitutional separation of powers, creating a federal Leviathan while simultaneously diluting democratic accountability in a way that shreds institutional constraints on the growth and reach of the federal government. The issue is not merely “the fear of executive abuse,” as Sunstein and Vermeule claim, but also congressional abdication and judicial acquiescence.

The administrative state denies Americans their freedom to be governed by rules and institutions created by their elective consent. Decrees and regulations issued by unelected bureaucrats reduce citizens to the status of subjects, contrary to the Founders’ intentions. The Progressive concept of “administration” in lieu of representative democracy represents a form of governmental absolutism that sacrifices neutrality, fairness, and due process on the altar of technical expertise. The system we dignify with the label “administrative law” is really not law at all. It is an evasion of law, properly understood.

Without the benefit of actual legislative direction, or actual courts bound by traditional rules of procedure, agency commands resemble long-discredited prerogative tribunals such as the Star Chamber. The Founders were understandably opposed to “extralegal” power once asserted by English monarchs, and when adopting the Constitution went to great lengths to prevent similar abuses from happening in the federal government.

It may be that the administrative state is essential to the modern welfare state, but that is not an argument on the merits. Sunstein and Vermeule recognize this, conceding (in a footnote!) that from the standpoint of the Framers, “the expansion of power of the national government [during the 20th century] is the major unanticipated development. The growth of the administrative state should be counted as unanticipated only insofar as it reflects that expansion—but not insofar as agencies wield discretion or have ‘binding’ interpretive and rule-making authority. We acknowledge that we cannot defend this controversial view in this brief space, nor need we do so” (emphasis added).

While disparaging the originalist bona fides of “the New Coke,” the authors remarkably acknowledge that even “if new historical work turns out to uncover unexpectedly strong originalist support for the New Coke,” judges should nevertheless decline to curb the administrative state because it is too late to turn back. “Settled practices, a product of felt necessities for a period of many decades, have their claims. Constraints and invalidations have costs, including democratic costs, and they might even endanger liberty, however it is understood.”

In other words, the unconstitutionality of the administrative state doesn’t matter. This same ipse dixit could have been rolled out in 1954 as a rationale for retaining “separate but equal.” The nation, after all, had gotten used to segregation over “a period of many decades.” Fortunately, self-serving apologies for the status quo went unheeded then, and they should also be ignored now. Taming the administrative state is the issue of our time.

Mark Pulliam is a contributing editor of Law & Liberty.