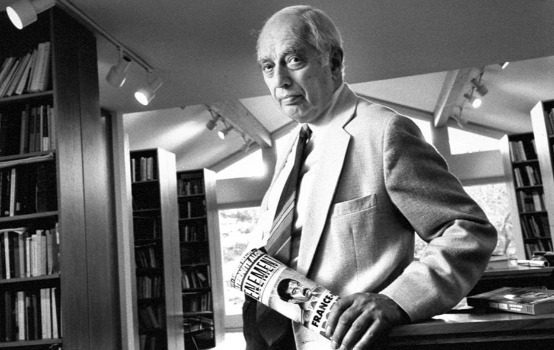

Bernard Lewis: The Bush Administration’s Court Intellectual

I encountered the late Bernard Lewis (1916-2018) during the 1990s culture wars, when historians and educators met full-frontal multiculturalism, a thematic force beginning to reshape U.S. and world history curricula in schools and colleges.

The two of us shared early, firsthand experience with Islamist disinformation campaigns on and off campus. Using sympathetic academics, curriculum officers, and educational publishers as tools, Muslim activists were seeking to rewrite Islamic history in textbooks and state and national standards.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations, created in 1994, was complaining of anti-Muslim “bigotry,” “racial profiling,” “institutional racism,” and “fear-mongering,” while trying to popularize the word “Islamophobia,” and stoking the spirit of ethnic injustice and prejudice in Washington politics.

Lewis and I were of different generations, he a charming academic magnifico long associated with Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study. He had just retired from teaching and was widely regarded as the nation’s most influential scholar of Islam. “Islam has Allah,” he said sardonically at the time. “We’ve got multiculturalism.”

Long before I met him, Lewis had alerted those who were listening to rising friction between the Islamic world and the West. This was, in his mind, the outcome of Islam’s centuries-long decline and failure to embrace modernity. In thinking this way, Lewis had earned the fury of the professor and Palestinian activist Edward Said at Columbia University, who wrote Orientalism in 1978.

Said’s influential book cast previous Western studies of the Near and Middle East as Eurocentric, romantic, prejudiced, and racist. For Said, orientalism was an intellectual means to justify Western conquest and empire. Bernard Lewis’s outlook epitomized this approach and interpretation. Said’s line of thought profoundly influenced his undergraduate student Barack Obama, and would have an immense impact on Obama’s Mideast strategies and geopolitics as president.

For some years, Lewis had warned of the ancient feuds between the West and Islam: in 1990 he’d forecast a coming “clash of civilizations” in Atlantic magazine, a phrase subsequently popularized by Harvard professor Samuel E. Huntington.

Throughout his long career, Lewis warned that Western guilt over its conquests and past was not collateral. “In the Muslim world there are no such inhibitions,” Lewis once observed. “They are very conscious of their identity. They know who they are and what they are and what they want, a quality which we seem to have lost to a very large extent. This is a source of strength in the one, of weakness in the other.”

Other examples of Lewis’s controversial, persuasive observations include:

- On jihad: “The object of jihad is to bring the whole world under Islamic law. It is not to convert by force, but to remove obstacles to conversion.”

- On the Crusades: “The Christian crusade, often compared with the Muslim jihad, was itself a delayed and limited response to the jihad and in part also an imitation. But unlike the jihad it was concerned primarily with the defense or reconquest of threatened or lost Christian territory.”

- On Sharia law: “The distinction of church and state, spiritual and temporal, lay and ecclesiastical is a Christian distinction which has no place in Islamic history and therefore is difficult to explain to Muslims, even in the present day.”

During the run up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Lewis suddenly gained immense political influence, love-bombed by White House neocons Richard Cheney, Richard Perle, and other policymakers to a degree that preyed on the old man’s vanity and love of the spotlight.

Anti-war feeling in official Washington then was unpopular. Among Republicans and Democrats alike, to assert that Israel and oil were parts of the equation appeared uncouth. Insisted the neocons and White House: the aim of the war was to bring democratic government and regional order to the Mideast. Rescued from despotism, Iraqis would cheer invasion, Lewis and his allies claimed, as Afghanis welcomed relief from Taliban fundamentalists.

In 2004 the Wall Street Journal devised what it called a Lewis Doctrine, which it defined as “seeding democracy in failed Mideast states to defang terrorism.” The Journal clarified that the Lewis Doctrine “in effect, had become U.S. policy” in 2001. The article also revealed that Lewis had long been politically involved with Israel and a confidant of successive Israeli prime ministers, including Ariel Sharon.

“Though never debated in Congress or sanctified by presidential decree, Mr. Lewis’s diagnosis of the Muslim world’s malaise, and his call for a U.S. military invasion to seed democracy in the Mideast, have helped define the boldest shift in U.S. foreign policy in 50 years. The occupation of Iraq is putting the doctrine to the test,” the Journal proclaimed.

And so it has gone. After 15 years of many hard-to-follow shifts in policy and force, with vast human and materiel costs, some analysts look upon U.S. policy in Iraq and the Mideast as a geopolitical disaster, still in shambles and not soon to improve.

In other eyes Lewis stands guilty of devising a sophistic rationale to advance Israel’s security at the expense of U.S. national interests. In 2006, Stephen M. Walt and John J. Mearsheimer accused Lewis of consciously providing intellectual varnish to an Israel-centered policy group inside the George W. Bush administration that was taking charge of Mideast policies. The same year, Lewis’s reckless alarmism on Iranian nukes on behalf of Israeli interests drew wide ridicule and contempt.

A committed Zionist, Lewis conceived of Israel as an essential part of Western civilization and an island of freedom in the Mideast. Though, acutely aware of Islam’s nature and history, he must have had doubts about the capacity to impose democracy through force. Later, he stated unconvincingly that he had opposed the invasion of Iraq, but the facts of the matter point in another direction.

Lewis thus leaves a mixed legacy. It is a shame that he shelved his learned critiques and compromised his scholarly stature late in life to pursue situational geopolitics. With his role as a government advisor before the Iraq war, academic Arabists widely took to calling Lewis “the Great Satan,” whereas Edward Said’s favored position in academic circles is almost uncontested.

Yet few dispute that Lewis was profoundly knowledgeable of his subject. His view that Islamic fundamentalism fails all liberal tests of toleration, cross-cultural cooperation, gender equality, gay rights, and freedom of conscience still holds. Most Islamic authorities consider separation of church and state either absurd or evil. They seek to punish free inquiry, blasphemy, and apostasy. Moreover, it is their obligation to do so under holy law. Wearing multicultural blinders, contemporary European and American progressives pretend none of this is so. As has been demonstrated since 2015, Europe provides opportunities for territorial expansion, as do open-borders politics in the U.S. and Canada.

In 1990, long before his Washington adventures, Lewis wrote in the American Scholar, “We live in a time when great efforts are being made to falsify the record of the past and to make history a tool of propaganda; when governments, religious movements, political parties, and sectional groups of every kind are busy rewriting history as they would wish it to have been.”

On and off campus, Islamists today use Western progressive politics and ecumenical dreams to further their holy struggle.

Lewis would point out that this force is completely understandable; in fact, it is a sacred duty. What would disturb him more is that in the name of diversity, Western intellectuals and journalists, government and corporate officials, and even military generals have eagerly cooperated.

Gilbert T. Sewall is co-author of After Hiroshima: The United States Since 1945 and editor of The Eighties: A Reader.

Comments