What Miniver Cheevy Means

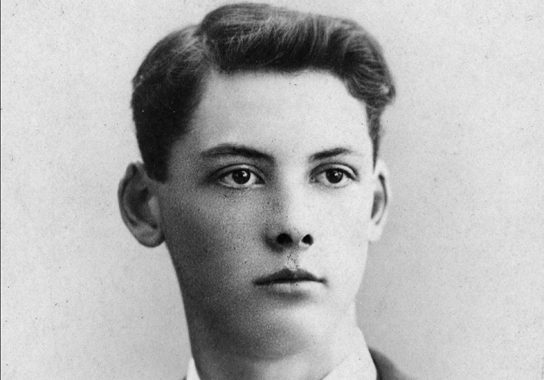

Every semester, on the first day of the poetry courses I teach, I hold up Lilla Cabot Perry’s portrait of Edwin Arlington Robinson and tell the students an only slightly embellished anecdote. This first great American poet of the 20th century, I begin, once stared out from the coast of Maine at the dark Atlantic waters stretching into the horizon’s gloom. A flask in hand, he watched the waves and considered the prospects of his chosen career. In Gardiner, where he lived, six persons read poetry out of a population of 6,000; there was about an equal number of drunks. Robinson estimated that the proportion held for the entire country. (The critic D.H. Tracy has speculated that this proportion is about right today, as well.) Perhaps a tenth of a percent of Americans appreciate poetry. With this sobering figure in his head, the aspirant poet twisted his flask and took another drink.

That you have enrolled in a poetry course—by choice, no less—automatically makes you a rare breed, I tell my class. Robinson would be happy.

That E.A. Robinson ever did know happiness should be a cause of wonder. As the poet Robert Mezey recalls in his edition of Robinson’s poems—and as Scott Donaldson, in his recent biography of the poet, describes in detail—the facts of the poet’s life would not seem a recipe for contentment. Born in 1869 in Head Tide, Maine, Robinson was the third in a family of three boys. His parents had been hoping for a girl, and such was their disappointment that they neglected to name the child for many months. When they were finally prevailed upon to do so, at a lawn party in the summer of 1870, they held a contest to name him by lot. A woman from Arlington, Massachusetts, drew the name “Edwin” from a hat, and so the infant had a name at last, clattering though it was with an ungainly triple rhyme that he would always loathe.

No longer nameless, Edwin still went unnoticed, save for a teacher’s blow in his 11th year that permanently damaged his inner ear. His family was upwardly mobile within the small society of Gardiner, and the older boys seemed promising. His oldest brother, Dean, became a doctor in town and flourished for a time, until self-medicating with opium undid his practice and his faculties. Robinson’s sonnet “How Anandale Went Out” is one of several pieces of evidence indicating Dean’s early death by morphine overdose was a suicide.

The second brother, Herman, also began well. He won the hand of Emma Shepherd, with whom Edwin was deeply in love, and left for St. Louis in pursuit of riches as a land speculator. With the panic of 1893, he lost his fortune and came back to Gardiner—the whole Robinson family, its prospects fading, under one roof once more.

Edwin’s father entertained no great hopes for him. After high school, Edwin lived on in the family house and kept it running. His father’s experience with Dean had made him cynical about college education, and Edwin might well have lingered on, the reliable and undistinguished servant of a failing family, for the rest of his years.

Three occurrences determined otherwise. First, Dr. Alanson Tucker Schumann, a local physician and leader of a circle of amateur poets, discovered Edwin had a talent for verse. Edwin may have been without a profession, but he felt sure he had a vocation—to be a poet. But his painful and increasingly deaf ear required treatment; and so, second, he was sent to a specialist in Cambridge and allowed for two years to enroll as a “special” student at Harvard. He did not distinguish himself as a scholar, but he delighted in the life of learning. A third decisive event occurred in 1896, the year his mother died. Back in Gardiner once more, Edwin watched as his brother withdrew into alcoholism. This gave him the chance to enjoy, in D.H. Tracy’s words, “the pleasant illusion of being married to Emma.” It could not last. Herman confronted him. Edwin departed for New York.

In the coming years he worked odd jobs there and elsewhere; he moved from hotel to hotel, never setting up a household of his own, nor finding an attachment to other women comparable to what he had felt for Emma. This would be his life: itinerant and detached. The year he left Gardiner, he published, at his own expense, The Torrent and the Night. Once in New York, he published a revised volume, The Children of the Night, methodically sending out copies for review. As Robinson the boy had been treated by his family, so Robinson the poet was treated by the literary world. “Nobody devoted as much as an inch to me. I did not exist,” he would later say.

Unfortunate, unloved, and drifting, Robinson “lived in and for his work,” as fellow poet and dramatist Louis O. Coxe observes. His faithfulness to poetry did not help him overcome the apparent unhappiness of his early life; it rendered his misfortunes a matter of indifference. He knew what he was born to do, and it showed. He possessed a “jarring wholesomeness as a man.” People just liked him. They handed him money and provided him shelter; the actress Isadora Duncan would offer him her amours, which he politely declined. He flopped from place to place, job to job, and waited for the world to discover the value of his verse.

That might never have happened had the son of President Theodore Roosevelt not shown his father some of Robinson’s poems. The president immediately wrote Robinson, seeking to help him. He reviewed The Children of the Night for the monthly magazine Outlook with the requisite Roosevelt enthusiasm. And he found Robinson a sinecure in the New York Custom House, where the man from Maine wrote and drank until the end of the administration. Robinson wished to be a poet; he did not seek presidential favors, and indeed he turned down two initial offers. He would be content, so long as he was sufficiently provisioned to go on writing poems. Again the obvious goodness and integrity of his character bore unexpected fruit: this otherwise meek, aimless, and unsettled man inspired a lasting affection in nearly everyone he met.

The poems came quickly. The books began to sell. His Collected Poems was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1922. He won a second in 1924, and a third in 1928. As he lay dying in 1935, Robert Mezey tells us, Robinson remarked, “As lives go, my own life would be called, and properly, a rather fortunate one.”

I have known Robinson’s poetry since my own adolescence; his were among the first poems I enjoyed. I have known something about his misfortunes, his family’s alcoholism (which did not entirely spare the poet), and his career’s salvation through the offices of a president for almost as long. But I cannot stop marveling at it all. Reading Robinson’s poems, one quickly detects the sadness of the stories behind them, the melancholy of his invented Tilbury Town mirroring the happenings in Gardiner. Yet as seems to have been the case with the man himself, the poems accept these sad details and give them form with a kind of indefatigable joy. Robinson’s poems invite us to delight in the good they derive from sorrow and loss.

A late sonnet, “New England,” describes the dour and emotionally dry reputation of Robinson’s native region. There, “children learn to walk on frozen toes,” he writes, and “Joy shivers in the corner where she knits.” But the whole sketch is set in scare quotes: “Passion is here a soilure of the wits, / We’re told” (emphasis mine). If you were told only the facts of Robinson’s life, you would think joy had died of cold very young, but he stands apart from such a judgment.

Robinson has a different tale to tell. We can limn it from reading just one of his best, most apparently melancholy poems, a portrait of “Miniver Cheevy.” It runs thus:

Miniver Cheevy, child of scorn,

Grew lean while he assailed the seasons;

He wept that he was ever born,

And he had reasons.

Miniver loved the days of old

When swords were bright and steeds were

prancing;

The vision of a warrior bold

Would set him dancing.

Miniver sighed for what was not,

And dreamed, and rested from his labors;

He dreamed of Thebes and Camelot,

And Priam’s neighbors.

Minever mourned the ripe renown

That made so many a name so fragrant;

He mourned Romance, now on the town,

And Art, a vagrant.

Minever loved the Medici,

Albeit he had never seen one;

He would have sinned incessantly

Could he have been one.

Miniver cursed the commonplace

And eyed a khaki suit with loathing;

He missed the mediæval grace

Of iron clothing.

Miniver scorned the gold he sought,

But sore annoyed was he without it;

Miniver thought, and thought, and thought,

And thought about it.

Miniver Cheevy, born too late,

Scratched his head and kept on thinking;

Miniver coughed, and called it fate,

And kept on drinking.

Robinson favored the Petrarchan sonnet for his shorter poems, as he did blank verse for of his longer narratives and dramatic monologues. In both modes, he distinguished himself for the plainness of his speech, its colloquial, flat, and sometimes obscure abstractions moving across the lines as if indifferent to where they end. (For an especially fine example, see his early sonnet, “The Clerks.”) “Cheevy” has some of that but shows him at his most inventive as well; the cross-rhyming quatrains run at tetrameters for three lines before coming to a clunking halt in the dimeter fourth line. Sentence rhythm adheres entirely to stanza form. In consequence, each stanza gives us a single statement of Cheevy’s affections and then undercuts it with a quick final stroke—a phrase that feels two notes short but also like a lingering afterthought.

Cheevy’s lachrymose character begins the poem in blank despair—“He wept that he was ever born”—before tipping and tunking into something else: “And he had reasons.” What is that last line? A mere dark corroboration on the part of the author? Or does it undermine the deathwish with a comic grin? Note that the second rhyme in each quatrain is feminine: “SEA-sons” with “REA-sons,” and even “SEEN one” with “BEEN one.” Does not that hypermetrical, falling syllable bring each observation to a clattering, clownish halt? The practice of such masters of feminine rhyme as Lord Byron and W.H. Auden suggests its effect is consistently thus.

In the third stanza, Miniver’s dreams are a consolation to him. Of what does he dream? Of “Thebes and Camelot,” the outposts of classical and medieval grandeur. Of the courage and chivalry of yore that beguile the idle mind of a neglected scholar stuck in the backwater of Tilbury Town. He has little else to while away the rest “from his labors.” But Miniver “dreamed of Thebes and Camelot … And Priam’s neighbors.” The sublime invocation of capitals of culture proceeds not to the equally emblematic king of Troy but to his “neighbors”: the all and sundry of ancient civilization.

Something similar happens twice in the fifth stanza, where Miniver’s love of the decadent Medici is detailed. Robinson qualifies his love with a concession: “Albeit he had never seen one.” He does the same with Miniver’s desire for the excesses of a red-blooded man of the Italian Renaissance: “He would have sinned incessantly / Could he have been one.”

The humor is at Cheevy’s expense: he is impotent much as T.S. Eliot’s “J. Alfred Prufrock” would be—Eliot’s poem was written the same year as Robinson’s was published—his aspirations to greatness frustrated by a personal inadequacy that Cheevy is swift to displace from himself onto the banality of his age. To paraphrase Eliot, he could have been Hamlet, if only Maine were Denmark and he a crown prince. In lieu of a title, Miniver “cursed the commonplace / And eyed a khaki suit with loathing.” His would be a different and better life if only the “mediaeval grace” could be made available again. Yes, the quatrain concludes, if only we could recover the elegance “Of iron clothing.” But we rely on tailors not armorers, and that change is indeed a loss—just not the shattering one that Cheevy’s heart says it is.

This last line is my favorite in the poem, but its hilarity may be surpassed by what immediately follows. He “scorns” at once the industrious and acquisitive age in which he lives and also his failure to share in its wealth. There’s an impasse here—one that exceeds the refusal of history to reverse course at the beck of nostalgia—and Robinson does not let us miss it: “Miniver thought, and thought, and thought,” we read, “And thought about it.”

In Robert Frost’s introduction to Robinson’s last book, King Jasper, he recalls meeting Ezra Pound in 1913 and reading these lines with him: “I remember the pleasure with which Pound and I laughed over the fourth “thought” … Three ‘thoughts’ would have been ‘adequate’ as the critical praise-word then was. There would have been nothing to complain of if it had been left at three. The fourth made the intolerable touch of poetry. With the fourth the fun began.”

For Robinson, the fun was there from the beginning. One does not need good fortune to rejoice, but only something to think and think about, some raw material out of which to make something fine. So Robinson delights in that final quatrain, which leaves Miniver stranded in reflective impotence, with a hint of a tubercular “cough,” a declaration of unhappiness at his “fate,” and a swig from his flask.

Robinson would later remark of this character and others like him that they were “sustained by dreams and soothed by drink. I certainly should know them. I’m one of them.” “Cheevy” would be no less a great poem were it just a frank expression of Robinson’s despair with his own fortunes. But it is not a poem of despair at all. E.A. Robinson, child of New England, looked with scorn on those who found his region joyless and cold. He greeted misfortune with amiability, and in his poems he turned it into well-wrought humor, and then he turned humor into a cause of joy. By this, I do not simply mean that Robinson identifies with Cheevy and must, therefore, be sympathetic to his nostalgia. That is true: Robinson viewed his career as a fight against “materialism” that resembles his character’s hatred of khaki suits. What I intend is something more intrinsic to the poem: the form of the poem, its metrical and syntactical structure, transforms mockery to companionship, failure to victory, sorrow to joy.

Robinson rejoiced his whole life long, his poems glittering with wry appreciation for the comedy of sadness. He had come into the world to write poems; in the world he knew, itself mired with suffering, he found the materials that would allow him to pursue his vocation and flourish. He asked for nothing more, and this faithfulness to the good he had been given seems to have preserved his character and to have made him an object of affection to nearly everyone who knew him. This is something to think and think about—that is, to study with the other six amateurs in town and to marvel at, and even to rejoice in.

James Matthew Wilson teaches in the department of

humanities and Augustinian traditions at Villanova University. His new volume of poems is The Violent and The Fallen.