Vonnegut Against War

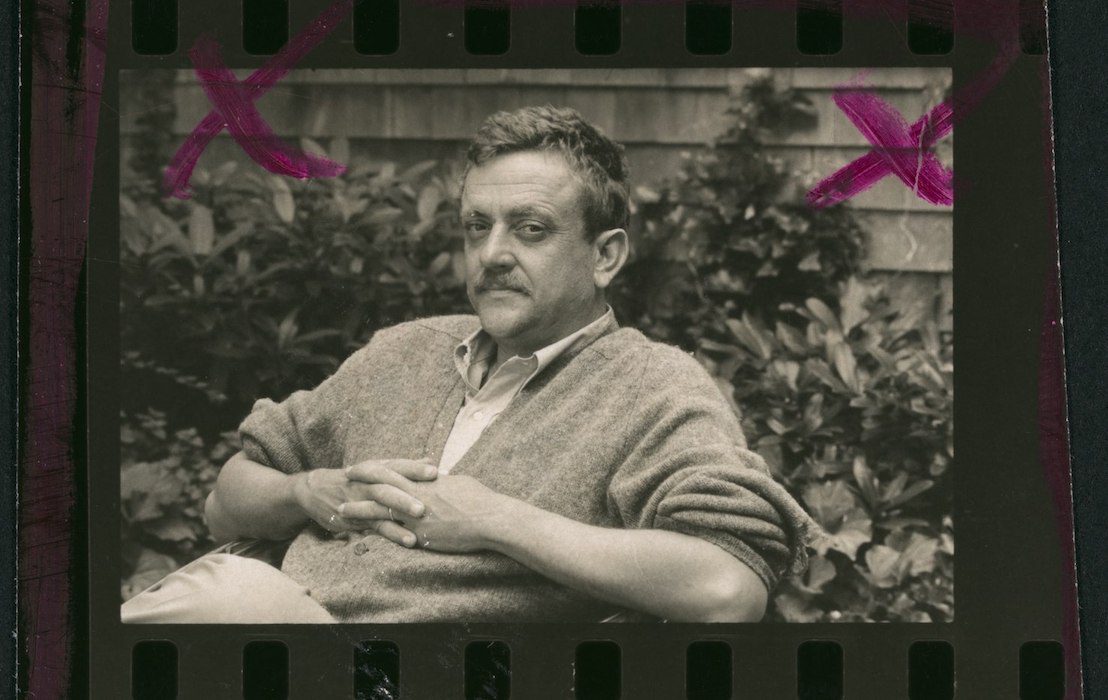

The Writer’s Crusade: Kurt Vonnegut and the Many Lives of Slaughterhouse Five, by Tom Roston (Abrams Press, 2021), 261 pages.

Forty-five years ago, fresh off the success of his classic novels Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions, Kurt Vonnegut wrote a little-read and even less well-remembered follow-up called Slapstick, or Lonesome No More! The critics were unkind but, as in so many things, it turns out that Vonnegut guessed right.

With the prescience of a quatrain by Nostradamus, the novel imagined a crumbling future in which America is beset by loneliness. The novel’s narrator mounts a presidential campaign in which he promises to confer sham middle names on the public with the goal of artificially enlarging extended families. Scientific experiments gone haywire in China causes the miniaturization of Chinese citizens, and some of these tiny men are inhaled by ordinary people, resulting in a pandemic of sorts.

Vonnegut, who died in 2007 at age 84, must be cackling somewhere with his smoker’s laugh. Yet even if Slapstick had not predicted a coronavirus-riddled, socially distanced and divided modern America, Vonnegut’s collected novels, short stories, essays, and speeches would reveal him to be a worthwhile reclamation project for Main Street conservatism.

If Trump supporters can look past Vonnegut’s avowed leftism—he was a devotee of the failed socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs—they will find plenty to embrace in his distrust of technological progress (Player Piano), contempt for the blandness and soullessness of mass culture (Breakfast of Champions), and suspicion of efforts to enforce equality by any means (the short story “Harrison Bergeron”).

Most of all, Vonnegut’s peace-loving, war-hating instincts, borne of his experiences as a POW who survived the Allied bombing of Dresden, mark him as the patron saint of a voting bloc weary of interventions in foreign lands and disgusted by the leaders who view such interventions as an immutable feature of nature, like a rock or a glacier. In the memoir-like first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut recalls telling film producer Harrison Starr that he was writing something akin to an antiwar book and being told by Harrison that he ought to write an “anti-glacier book instead.” “What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers,” Vonnegut writes.

This is an appealing brew for those on the modern right: Vonnegut combined a homespun Taft-style opposition to foreign entanglements with a pragmatic Burke-style recognition that humanity was unlikely to slough off its propensity for warfare any time soon. “So it goes,” as the man said. None of this is to deny Vonnegut’s left-wing politics or ebullient atheism, but to admit the obvious: Like Pete Seeger or Studs Terkel, Vonnegut was an adherent of a humane, back-to-the-earth species of liberalism that is utterly distinct from the militancy and hatefulness of today’s left.

Tom Roston’s new book about the origins and legacy of Slaughterhouse-Five offers a stark reminder of Vonnegut’s uneasy position with contemporary liberalism. A former writer at The Nation, Roston is an unapologetic fan—in an author’s note, he fondly remembers receiving a call at the magazine from Vonnegut, who wrote him a check for $50 to look up the Cambodian word for “morning sun”—and he has done plenty of research and original reporting here. Roston ransacked archives to scrutinize the early drafts, false starts, and anxious correspondence that accompanied the creation of Slaughterhouse-Five, and he seems to have spent many hours soliciting quotes from Vonnegut scholars, admirers, and other interested parties, not to mention three of his grown children, Mark, Edith, and Nanette. Yet all of this honest effort has resulted in a book that fails to convince in its central argument that Vonnegut’s masterpiece, not merely an antiwar novel, is a sort of covert brief on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Roston starts on the wrong note by repeating an anecdote that, he repeatedly emphasizes, he does not believe and certainly cannot prove: After they were liberated, Vonnegut and his fellow POW Bernard V. O’Hare—it is Bernard’s wife, Mary, who in the opening section of Slaughterhouse-Five famously counsels Vonnegut not to romanticize a war fought by “babies”—chased down a particularly evil German prison guard and murdered him. Roston heard about this story from the son of Bernard and Mary, Bernie, who in turn learned about it from a Vietnam War veteran, John Kachmar, who claimed that he had, decades ago, met his father and, later, Vonnegut. “And he left me with the distinct impression, if not the words, that they had killed the guard,” Kachmar told Roston, referring to the elder O’Hare. “Or at least roughed him up pretty bad.”

That Roston doubts this killing actually took place—and that he failed to corroborate it with anyone—doesn’t stop him from going to town with the purported revelation. He admits to getting a charge out of a revenge stories generally and especially one that adds a touch of moral complexity to a figure as benign and grandfatherly as Vonnegut. He writes that “for a time” the provisional title of the book was Kurt Vonnegut, Nazi Slayer! Yet Roston, here and throughout, pulls his punches: Not only does he admit doubting the incident, but so does most everybody else he talks with, including the Vonnegut offspring. “I doubt the story,” Edith says. “But go ahead with it. It can be valuable.” Or not. Roston references a passage cut from Slaughterhouse-Five in which the speaker references a promise he made to himself to kill a Nazi guard—but then Roston backs off. “Could this be a veiled confession? Not necessarily,” he writes.

Roston by and large moves on from this unsubstantiated anecdote, but the fact that he dwells on it as long as he does suggests an author trying to fit a round hole into a square peg—in this case, to turn one of the world’s most noted pacifists (“I have told my sons that they are not under any circumstances to ever take part in massacres, and that the news of massacres of enemies is not to fill them with satisfaction or glee,” Vonnegut writes in Slaughterhouse-Five) into a potential character in Inglourious Basterds.

As long as he sticks to the agreed-upon facts of Vonnegut’s life and work, Roston is on solid ground. He ably recounts Vonnegut’s childhood in Indianapolis—where he was the beneficiary of a family of “freethinkers,” including his great-grandfather Clemens, who wrote, “Be aware of this truth that the people on this earth could be joyous, if only they would live rationally and if they would contribute mutually to each other’s welfare”—and his war service, culminating, of course, with the historical fluke of his witnessing the destruction of Dresden.

Back home, Vonnegut flailed to a certain extent: Neither a degree in anthropology at the University of Chicago nor a stint as a reporter with Chicago’s City News Bureau panned out, and soon he and his young bride, Jane, pulled up stakes for upstate New York. He tried to hold down respectable day jobs—including doing public relations for General Electric and running a Saab dealership—but eventually bet on himself as a full-time writer of fiction. Like an automaton, he pumped out skillful, polished short stories for all the best magazines while dreaming up his eccentric early novels, including The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle.

Yet despite his perception of himself as a “hack” who would write anything, Vonnegut seems to have sensed that—despite ample family drama, including the suicide of his mother while he was overseas—the Dresden experience was, for all of its horror, the closest thing he had to an obvious subject. He admitted as much later in life. “I wrote this book, which earned a lot of money for me and made my reputation, such as it is,” Vonnegut said. “One way or another, I got two or three dollars for every person killed. Some business I’m in.”

Not that Vonnegut was actually so cynical. After years of trying to settle on the right approach for what he called his “famous Dresden book”—Roston describes a number of the book’s failed iterations—the political turmoil of the late 1960s unlocked the key that led him to finally conceive Slaughterhouse-Five in the form we know today. “I think the Vietnam War freed me and other writers, because it made our leadership and our motives seem so scruffy and essentially stupid,” Vonnegut once wrote. “We could finally talk about something bad that we did to the worst people imaginable, the Nazis. And what I saw, what I had to report, made war look so ugly.”

It’s enough to say that Vonnegut was that purest of creatures, an evangelist against all war in all of its varieties and no matter its aims, but Roston won’t stop there. He does backflips and somersaults to suggest that the novel’s “unstuck in time” protagonist Billy Pilgrim suffers from PTSD. As we all know, Billy claims to bounce around time freely—from Dresden to suburbia to the faraway planet of Tralfamadore. For Roston, this is not literary artifice but evidence of a mental state that Vonnegut intended to be reminiscent of flashback-addled PTSD sufferers. To make his case, Roston even subjects Billy to a questionnaire found in a Veterans Administration brochure detailing PTSD symptoms; Billy “answers” three of five answers in such a way to raise the possibility of a “diagnosis.”

While Roston credibly asserts that Billy was based in part on another POW, one who died overseas and who did have symptoms consistent with PTSD, Edward Crone, he is on shakier ground when he dances with the idea that Vonnegut himself had PTSD—an idea given credence by his son Mark but one that others dismiss and which seems inconsistent both with Vonnegut’s generally well-adjusted, nonviolent life and his consistently stated, darkly humorous opinion that Dresden was, in some ways, nothing more than grist for his literary mill. To most of us familiar with Vonnegut as a public figure, he seemed like a happy warrior.

Roston quotes from interviews with veterans whose service exacted psychological tolls and who find resonance in Slaughterhouse-Five. Their opinions on the novel, while interesting, hardly have the authority of Gospel, though. To his credit, Roston also quotes cooler heads, including Vonnegut scholar Jerome Klinkowitz, who, arguing against the PTSD line, says, “When Kurt wants to make a literary character, he is not writing a psychological study. He is crafting a work of art.” But in the end he can’t help himself: Even when he equivocates on Vonnegut’s intentions or the state of his mental health, he sees the author through the prism of modern psychiatry.

The trouble here is that Vonnegut’s large and abundant hatred for war is telescoped into personal suffering. Vonnegut opposed war not because it made him feel bad—or led him to drink, or caused him to be a caring but sometimes distant dad, or made him dream up Tralfamadore—but because it was wrong. He was not a spokesperson for PTSD but an old-fashioned liberal, one who, perhaps more than ever, needs rescuing by commonsense conservatives.

Peter Tonguette is a frequent contributor to the Wall Street Journal, Washington Examiner, and National Review.