Trouble With Tradition

Tradition is our business. In the present moment, this also means trouble is our business. To lay claim to the Christian tradition as a participatory reality, rather than a static legacy of creeds and curios, is to assert that the tradition takes an active role in culture. And this, in the parlance of our times, is “troubling,” as it seems certain to require either the reckless marriage of secular and sacred or the bastardization of the holy in pursuit of the profane. Concern about the former typically issues from functionally secular, pluralistic types, whose approval of religion as a private endeavor sits uncomfortably with their disapproval of religion as a public enterprise. The latter charge commonly issues from certain Christian circles, in which, as a representative triumvirate of the post-liberal order recently articulated in TAC, “cultural Christianity” is viewed as “insincere and hypocritical, tawdry and chauvinistic.”

To both camps, the tradition is trouble. To Cluny Media, the publishing house for which I serve as editor-in-chief, however, the tradition is our business. One year ago, almost to the day, Sohrab Ahmari and I had a fascinating (at least to me) conversation about Cluny, its mission, and its work. (The fruits of that conversation appeared in First Things.) Inspired in large part by Cluny’s reissuing of Jean Daniélou’s Prayer as a Political Problem, our discussion turned quickly to Cluny’s work as a means of integrating Christianity to the culture, and, in doing so, directly opposing the liberal order’s penchant for dis-integrating Christianity from the culture.

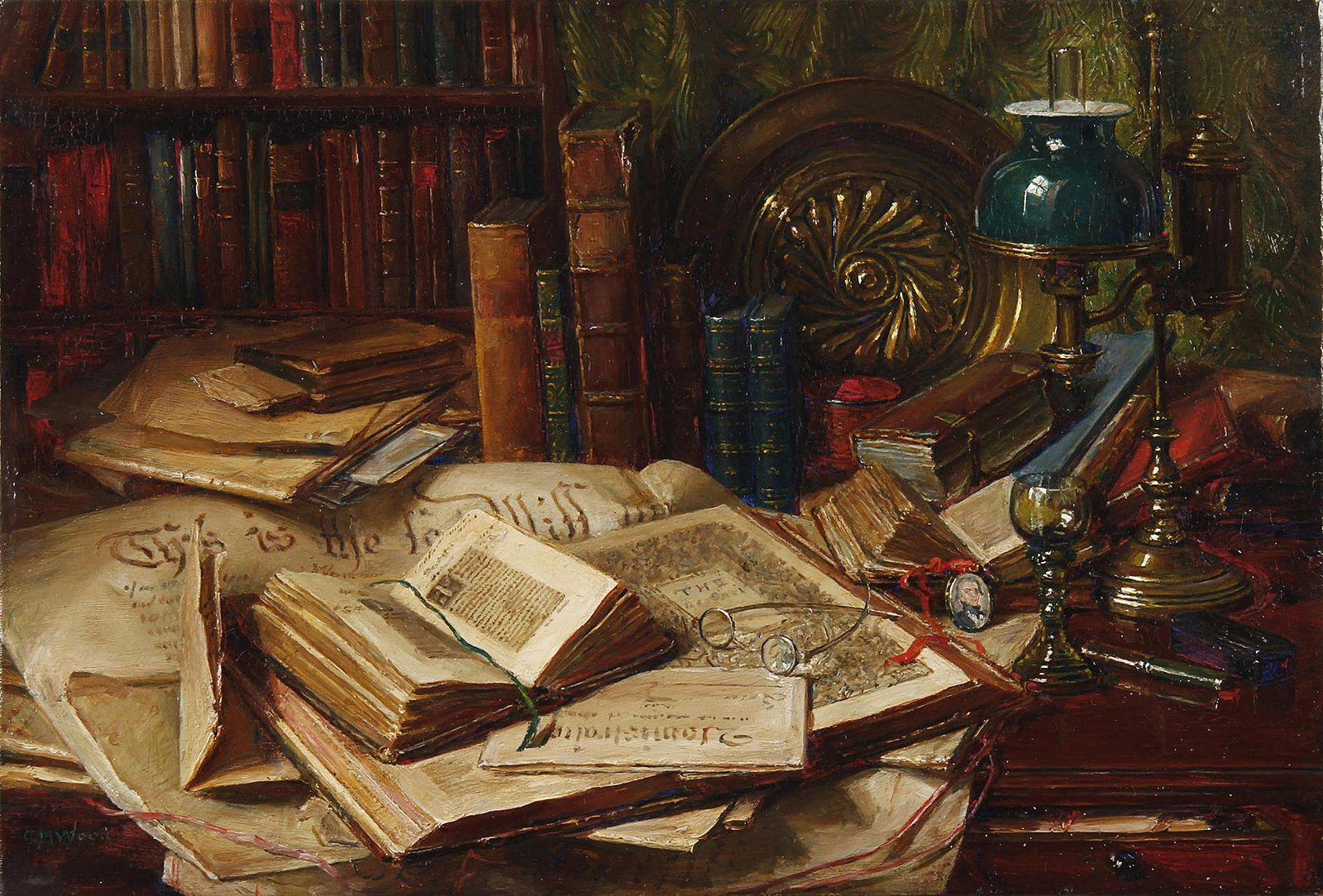

For Cluny, the contribution takes the specific form of republishing books, of re-presenting the past to the present via out-of-print, hard-to-find, or just generally neglected literature from the (predominantly) Catholic past. We take as our fundamental premise that the past is something worthy of attention, precisely because the lessons of the past are necessary for the care and cultivation of the culture of the present and its promise for the future. The tradition cares and maintains these lessons. Or, stated differently, the tradition houses truths about the human experience and offers instruction in the ways of wisdom and folly.

The preservation of the past is aimed at the good of the future—and, implicitly therefore, of the present. Gleaning insight from medieval culture, Johann Huizinga argued that culture requires “a code by means of which people understand one another. Everyone is assumed to have mastered the rules of the game.” Culture thus “presupposes a certain degree of dogmatism, of rigidity in thinking,” as well as—and hence the contemporary dissolution of culture—“an absence of the awareness of a general interdependence and relativity of all our concepts and notions which is the constantly present characteristic of modern thought.” Once any of those elements goes missing, culture breaks down, fragments, individualizes. And such is precisely what has happened at present, as seen in our “deracinated, gnostic deformations of Christianity.”

To prevent this occurrence—or to reverse its curse if it has already occurred—there is a consideration primary even to the political: the raw record of tradition, the literary legacy that has fallen into disrepair and neglect. The premise of Cluny’s mission is that the tradition offers the requisite guidelines, Huizinga’s “rules,” for competent engagement in the cultural game. All our efforts to defend Christian civilization, to rebuild cultural Christianity, will be fruitless if we neglect the tradition in a mode which precedes the political: the literary.

In the twelve months since Ahmari and I spoke, Cluny has published fifty-five books, all but of one which were republications. The range in subject, style, and sensibility for these books is astounding. Yet, for all that, they do possess a higher unity. From Josef Pieper’s Hope and History, Emmanuel Mounier’s Be Not Afraid, and Karol Wojtyła’s A Sign of Contradiction, to Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede, José María Gironella’s One Million Dead, and Gerhard Fittkau’s My Thirty-Third Year: each book occupies a place in the tradition precisely because it illuminates in some particular, powerful way the mystery of being.

A central, and often confounding, element of that mystery is its multiplicity and diversity, as Thomas Aquinas long ago described. This element plays itself out across all of creation, but most especially in its apex: the human person, who alone of God’s creatures possesses the capacity to know truth and reject falsehood, to love good and avoid evil, to “attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God” himself. The past, the tradition, holds plentiful literary examples of attempts to plumb the strange depths of this capacity.

Contemporary debates about the relationship between Christianity and culture are replete with appeals to the tradition, to the classics, to the grand inheritance of the philosophia perennis. In the course of my work at Cluny, it has become ever more clear that these appeals are bound to fail if and when they evade the tradition’s demand for active participation: we have to participate as players, not as neutral spectators or detached analysts. The tradition is a democratic reality, as Chesterton stated with characteristic brilliance: “Tradition…is the democracy of the dead.” As a democratic reality, then, the tradition requires an engaged citizenry. It requires participants with a stake in the game. As participants in the tradition, we cannot stand at a distance and simply take stock of the past; we must take a part in it, understanding its content, appreciating its authority, desiring to achieve its goals, and wanting to conclude our efforts as winners.

Once an activity, such as the tradition, is understood as something that requires participation, and thus as something that can be properly conceived as a “game,” we can figure out what kind of game it is. What makes it this particular game, and not some other? This raises the further question of content. The recently established, ambitious Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, for example, is certain to take up this question. The program aims to develop thoughtful readers and writers in and of the Catholic tradition who will wrestle with that question of content. Yes, we humans are readers and writers, but readers and writers of what? What will be the means by which we win the game, or the means by which we improve how we play?

Ideally, the answers to these questions would involve drawing from those “deep wellsprings of Christian culture.” Yet no one can draw on wellsprings dug out of sight and out of mind. To draw from these wellsprings, we must first possess a means of reaching them. Hence the necessity to lay claim to the tradition as a dynamic reality in which we can actually participate and through which we can meet the past head on and work to integrate it into the present. This requires repairing the bridge between “the sacred and the natural,” as Daniélou contended in Prayer as a Political Problem.

Our tragedy today is that the bridges between them have been cut. A means of presenting one to the other is lacking; there is no imagery that can serve this role. While science cannot give a picture of itself, the world of the sacred lays emphasis on imagery. Art can place itself at this frontier.

Daniélou’s provocative diagnosis of the tragedy and his prescription for its treatment involves a complex understanding of “art.” While he goes on to mention painting as one example, it is evident that “art,” for his purposes, should be more accurately apprehended as “human creativity,” generally speaking. By opposing it to science and technology, he places it squarely in the realm of the creative, the imaginative, the distinctly human. The crucial clue, however, resides in his comments on myth: “Here we touch on a point which is essential to the actual problem: the elimination of myths. Art comes directly into the question.” Art, then, for Daniélou’s purposes (and for Cluny’s), is the outcome of humanity’s storytelling capacity. This capacity is what is responsible for the articulation and circulation of the mythos of an order, a culture, even a Church.

And no art form offers this mythos more profoundly than does literature. Yes, art as music, painting, engraving, sculpture, film bring the myth to bear and build a bridge between the sacred and the natural. But, as Josef Pieper noted, “it is above all in the word that human existence comes to pass.” Hence the need for an intensified and intentional engagement with our tradition, for renewed participation in the active and dynamic re-presentation of the past to the present as “a good that is common,” such that it can transform those who receive it into being more fully alive, more fully human, and more closely approaching the mind and heart of God.

John Emmet Clarke is editor-in-chief of Cluny Media.