Resuscitating Kipling

There’s a 20th-century British novel everyone should read. It’s about an orphan boy with special parents. He grows up in squalid circumstances until his adolescence, when a stranger who knew his parents helps him attend a faraway school he had never heard of, where he learns skills he calls “magic,” along with others who share his special ancestry. He develops a close relationship with a father figure who occasionally visits him at school. He goes on adventures and works to stymie the plans of powerful enemies. After his schooling, he works for a special government organization that sends him on high-risk secret missions. Of course, I don’t mean Harry Potter—I mean Kim, by Rudyard Kipling.

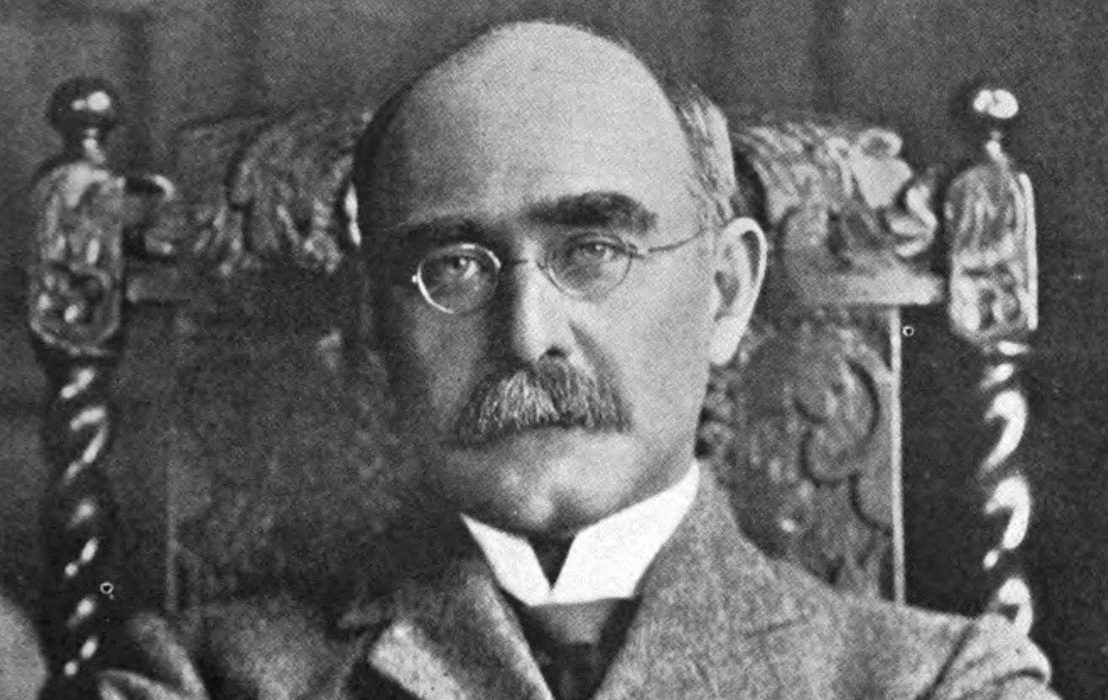

No one notices that Kim has the same plot as Harry Potter (or Harry Potter as Kim) because no one reads Kipling anymore. No one reads Kipling anymore because he has been judged to be, as Orwell put it, “a jingo imperialist… morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting.” In other words, he was canceled. By writing stories and poems about the functionaries of a dominant colonial power, Kipling associated himself with our time’s most abhorred political practices, including Western colonization of weaker nations and political control of darker-skinned people by lighter-skinned ones. Orwell wrote, “During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him.” The despising has continued through the generations since.

Among other things, Orwell despised Kipling for a “definite strain of sadism in him.” This is a serious charge and it deserves serious evidence, but Orwell did not offer any except to say that many of Kipling’s stories included violence and physical pain. To speculate confidently about inner psychology based only on an artist’s subject matter is presumptuous to say the least, and we might as well say that Spielberg must enjoy situations in which children’s lives are threatened by sharks and dinosaurs.

Reading Kipling seriously will show that, in fact, he was a sensitive and morally serious man. Consider the moment in The Jungle Book when Mowgli leaves his jungle family to meet other humans for the first time:

Then something began to hurt Mowgli inside him, as he had never been hurt in his life before, and he caught his breath and sobbed, and the tears ran down his face.

“What is it? What is it?” he said. “…Am I dying, Bagheera?”

“No, Little Brother. That is only tears such as men use,” said Bagheera. “Now I know thou art a man, and a man’s cub no longer…. Let them fall, Mowgli. They are only tears.”

Kipling was interested in what it meant to be a man rather than a boy. A sadist might define a man as someone strong and dominant and able to subjugate the weak to his will. But Kipling, through Bagheera, said that weeping is the activity that definitively demonstrates manhood. Babies cry, and children shed tears when they skin their knees, but Bagheera has recognized the “tears such as men use,” and these are what prove that Mowgli is no longer a “cub.” To understand weeping as a fundamental manly activity is the perspective of a sensitive artist, not a sadist.

Along with sadism, Orwell’s charge of “jingoism” is the other claim that has discredited Kipling through the generations. Again, we should look deeply into his published work to investigate the accusation. His most extensive and direct dramatic treatment of colonialism was “The Man Who Would Be King,” a story first published in 1888. The story describes a pair of common swindlers who hatch a plan to use trickery and force to become local kings in Afghanistan and enjoy being waited on by servants in a life of easy leisure. The outcome for these crooks is not the glory and kingly ease they desire, but rather the failure, madness, and death they deserve. The story shows colonial ambitions as the folly of scoundrels.

Yet Kipling expressed support elsewhere for the various colonial adventures of Britain and America. Why did he support colonial efforts after portraying their wickedness so vividly in his story? The answer is that Kipling viewed colonialism in much the same way that others have viewed war: as a difficult, thankless toil that can lead to either positive humanitarian outcomes or awful darkness, depending on how it is practiced. The exploitative motive for colonization is wicked and ruinous, but it is not the only possible motive. Kipling believed that conquering a foreign nation, if done in the right ways with the right motives, can be a way to provide millions with a better way of life, to “seek another’s profit” and to serve the “captives’ need.”

Before you laugh or sneer, note this feeling is apparent even today, even on the left, in the responses to the American withdrawal from Afghanistan. Many have mourned that the withdrawal will certainly lead to enormous harm to the lives and rights of women who now have to live indefinitely under the Taliban. This feeling is common on today’s anti-nationalist left, and yet the sentiment depends on a recognition that two potential ways of life are vastly different, and upon making a judgment that one reliably leads to greater flourishing and the other inevitably to wretchedness. For those who make this judgment, it’s easy to believe that conquering a foreign nation, if done in the best way and with the best motivation, can free the wretched from the yoke of their oppressors.

This is the thought process of a colonialist like Kipling, and the women’s-rights flavor of it is not even far-fetched if you consider the British banning of suttee—widow burning—in his native India. Kipling believed that his civilization offered greater scope for human flourishing than any available to the inhabitants of other nations. To believe that women are better off in America than under the Taliban, or to believe that Cubans are better off in Miami than in Havana is to have some version of this belief. Kipling wished for careful but energetic action to provide the benefits of his civilization to others, believing the remedy for pernicious authority is good authority, not no authority. Since Kipling’s time, we’ve lost both civilizational confidence and the bravery to take difficult, risky actions, and this partially accounts for our anti-colonial outlook. Though we may disagree completely with Kipling, at least we should recognize that his colonial instincts don’t make him a monster, and certainly don’t make his works unreadable.

In fact, Kipling’s ideas about foreign policy and grand strategy are quite hard to find in most of his writing. He was primarily interested in the rank and file: the common soldier who spoke in the vernacular and who actually did things instead of just talking about them. The world of high-government foreign policy is extremely far removed from anything considered by most of Kipling’s characters, like the “Tommy” who laments in Barrack-Room Ballads:

I went into a public-‘ouse to get a pint o’ beer,

The publican ‘e up an’ sez, “We serve no red-coats here.”

The soldiers of the barrack rooms who fascinated Kipling were interested in the common concerns of common men: getting a pint of beer, being respected by one’s fellows, and staying alive in a dangerous world. To love and admire this common soldier is not the same as blindly supporting the foreign policy that sent him on imperialistic adventures abroad.

My hero, Borges, was an avowed admirer of Kipling. He wrote that “Kipling saw war as an obligation, but he never sang of victory, only of the peace that victory brings, and of the hardships of battle.” To love peace and sympathize with hardships, to write almost always about common soldiers’ concerns but very rarely about generals’ grand plans, and to never sing of victory, is not how a jingo would write.

Borges went even further than defending Kipling, and expressed positive admiration for his gifts as a writer. When asked to “declare my aesthetics,” Borges wrote that he had learned “a few tricks” about writing, including

“…narrating events (this I learned from Kipling and the Icelandic sagas) as though I didn’t fully understand them…”

Kipling saw the world as big and full of dazzling, barely comprehensible multiplicity; this is a worldview that anyone who has spent extended time in India can understand. His character Kim marvels, like Kipling did, at the exciting bustle of the crowded world:

Kim sat up and yawned, shook himself, and thrilled with delight. This was seeing the world in real truth; this was life as he would have it—bustling and shouting, the buckling of belts, and beating of bullocks and creaking of wheels, lighting of fires and cooking of food, and new sights at every turn of the approving eye.

…

Kim was in the middle of it, more awake and more excited than anyone, chewing on a twig that he would presently use as a toothbrush; for he borrowed right- and left-handedly from all the customs of the country he knew and loved.

Novelists, of course, often insert themselves into their novels. It is easy to see Kim as an avatar of Kipling. Both were foreign-born British boys who loved adventure and loved India with all their hearts. Kipling borrowed subject matter and names from India like Kim borrowed customs. And maybe Kipling’s borrowings went even deeper. Consider that the most striking thing about Kipling’s poems is their meter. Their tight construction gives them an energy and force that almost pushes the reader forward; this makes them easy to memorize or even sing. Intricate, memorizable meters are also crucial features of Sanskrit poetry. Kipling’s love of adventure, his concern with manliness, his appreciation of the vernacular, all may have combined with the rhythmic meter of the Indian nursery songs he imbibed as a little child to form a powerful style all his own:

Kabul town’s by Kabul river—

Blow the bugle, draw the sword—

There I lef’ my mate for ever,

Wet an’ drippin’ by the ford.

Kipling was an internationalist, but one who knew both the folly of trying to rule Afghanistan and the pathos of leaving a comrade in Kabul. He was a moral thinker who carefully considered how to be a man. He was a poet whose meter sticks with you long after you finish reading. But more than anything else he was someone who could tell a rollicking good story, one that enchants the reader, if only for a moment. So much of today’s fiction is impenetrable, cynical, and unromantic, and so it is all the more important to remember and study the few writers like Kipling who can, now and then, bring magic to their readers’ hearts.

Bradford Tuckfield is a data scientist and writer. His personal website can be found here.

Comments