Lovers of Lost Causes

The Poets of Rapallo: How Mussolini’s Italy shaped British, Irish, and U.S. Writers, by Lauren Arrington, (Oxford University Press: 2021), 256 pages.

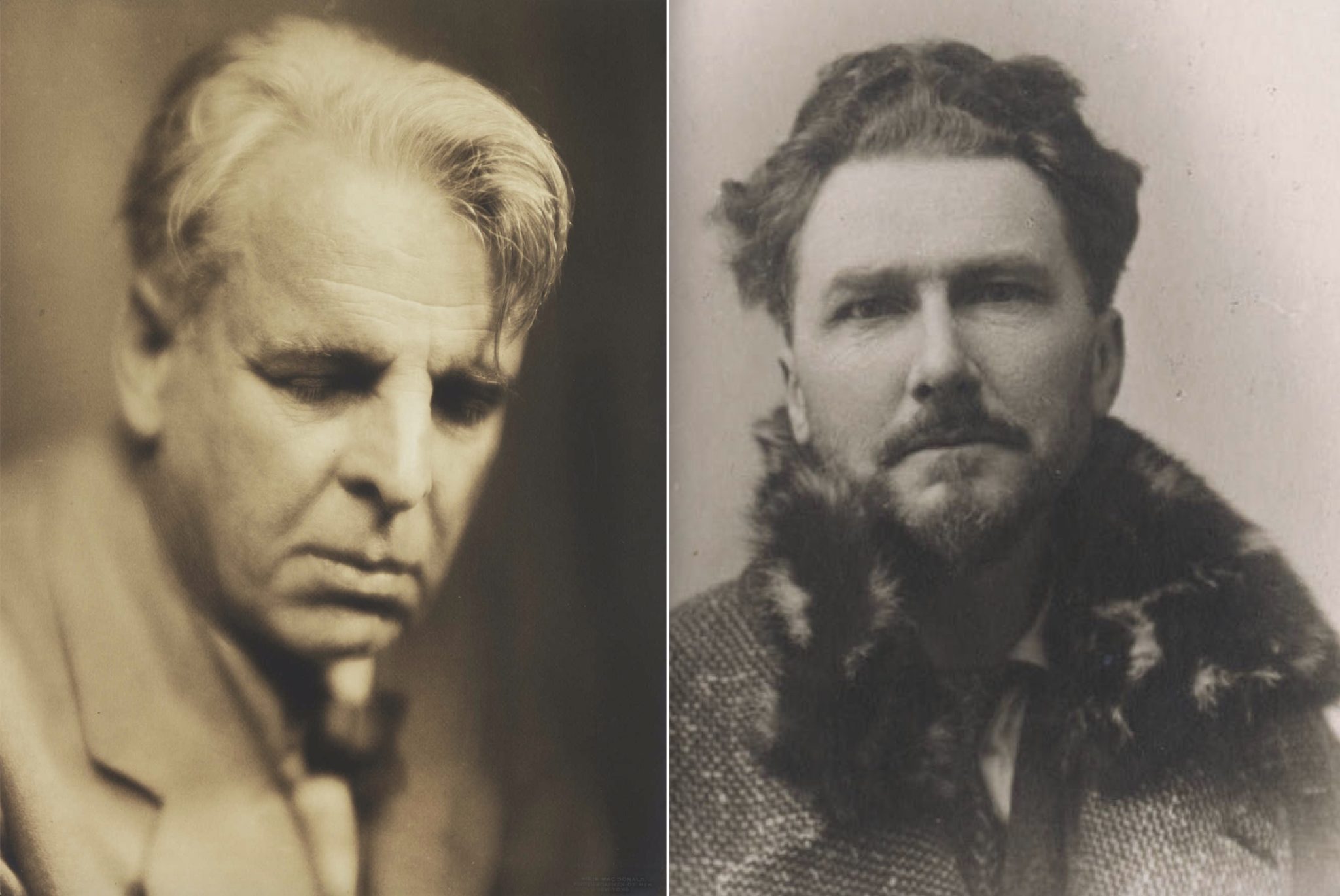

In January of 1929, a 63-year-old William Butler Yeats was speaking with Richard Aldington and Brigit Patmore—a second- and a third-rate writer, respectively—at a dinner party in Rapallo, Italy, when he posed to his companions an impossible question: “How do you account for Ezra?”

He was speaking, of course, of Ezra Pound, the American expatriate poet around whom this circle in Rapallo had revolved for half a decade, ever since he’d escaped there from the chaos of the Paris literary scene. “Here we have in him,” Yeats went on, “one of the finest poets of our time, some erudition and a high intelligence, and yet he is sometimes so—amazingly clumsy—so tactless and does what one might call outrageous things.” (Of course, Yeats’ perception of “outrageous things” may have been a bit skewed, given that he was, at that moment, wearing wool socks in place of gloves to protect against the frigid seaside air.)

The question asked then in real time—hardly out of earshot of Pound himself—has become one of the great political-literary quandaries of the past century: How do we account for the fact that one of the great American poets became a fervent spokesman for America’s wartime enemy and a leading light of foreign culture, only to be locked up in his home country for more than a decade at war’s end?

The Yeats-Aldington-Patmore anecdote, borrowed from Patmore’s own My Friends When Young, opens the second chapter of The Poets of Rapallo: How Mussolini’s Italy shaped British, Irish, and U.S. Writers, a new study of the Anglophone poets of Italy—especially Yeats and Pound, but also somewhat lesser figures like Thomas MacGreevy, Basil Bunting, and Louis Zukofsky—in the interwar period, by Maynooth University professor Lauren Arrington.

Arrington’s book is a fine work of history. From memoirs, letters, periodicals (including Pound’s fascinating little Rapallo magazine The Exile), and other sources she reconstructs in vivid detail a largely unappreciated era in the history of 20th-century poetry, and makes a compelling case for its consequence in the progress of the art.

But in answering the fundamental questions that underlie and drive the narrative, Arrington has difficulty. How do we account for Ezra? Arrington leans into Yeats’ derisive casting of Pound’s young acolytes—most of the men veterans of the Great War—as “shell-shocked Walt Whitmans,” attempting to cast Pound himself as some kind of latter-day Whitman abroad. She relies on a dispatch of Samuel Hynes from 1953, just over halfway through a then-elderly Pound’s imprisonment in St. Elizabeth’s, describing the 68-year-old poet as an “American Sage, descended in a direct line from Walt Whitman.”

Both Pound and Whitman were American; both wrote poetry, or professed to. But there the similarities end. Whitman is, in many ways, the bard of American liberalism: an exuberant narcissist singing his own praises, formed in adulthood by liberalism’s great military triumph (the American Civil War). Pound, meanwhile—while himself a raging narcissist and an odd kind of individualist—would hardly appreciate comparison to the Lincoln-worshipping homosexual champion of the American idea.

Arrington thus papers over much of the complexity of Pound’s own writing on his predecessor. The famous claim, for instance, that “[Whitman] is America” can hardly be read without the context of the sentences that follow: “His crudity is an exceeding great stench, but it is America. He is the hollow place in the rock that echoes with his time. He does ‘chant the crucial stage’ and he is the ‘voice triumphant.’ He is disgusting. He is an exceedingly nauseating pill, but he accomplished his mission.” The appreciation Pound admits for the best of Whitman’s verse—even his public amends in “A Pact,” published seven years later—can hardly be taken as straightforwardly as Arrington seems to do. His claiming of “America’s poet” as a “spiritual father” is tinged with bitterness.

This is an early essay, but Pound’s feelings about his home country hardly softened through the years. In The Exile two decades later he wrote simply: “America is the most colossal monkey house and prize exhibit that the world has yet seen.” In justifying his establishment of that journal he was even more direct: “I also want a place where I can speak freely concerning certain superstitions and idols of the American people which, as Molochs and other superstitious fetiches, are deeply reverenced by many, and are for that all the more hideous.” He held no quarter for the American religion whose foremost hymnist was Whitman, even as he grappled with his own descent from it.

It is Yeats, though, who offers the stronger repudiation of the malignant individualism America was then exporting into Europe. In “If I Were Four and Twenty,” a 1919 essay in which the aging poet-statesman constructs the manifesto he would embrace if he were thirty years younger, he suggests that:

social order is the creation of two struggles, that of family with family, that of individual with individual, and that our politics depend upon which of the two struggles has most affected our imagination. If it has been most affected by the individual struggle, we insist upon equality of opportunity, ‘the career open to talent,’ and consider rank and wealth fortuitous and unjust; and if it is most affected by the struggles of families, we insist upon all that preserves what that struggle has earned, upon social privilege, upon the rights of property.

The former option recalls the “idolatry of freedom and equality” Pound associated with the feminine. Citing this essay, Arrington recounts how Yeats, in the aftermath of the Great War and the early days of the Irish War of Independence, “imagines a total culture encompassing literature, drama, and even economics, all arising from the core principle that ‘the family is the unit of social life, and the origin of civilization which but exists to preserve it.'” Arrington worries that this “could be regarded, from the point of view of the 1930s, totalitarian rhetoric.” I would just call it common sense.

Disdain for their particular political prescriptions notwithstanding, at no point in this book does Arrington appear to take seriously the Rapallo circle’s underlying belief—certainly Pound’s—that the first decades of the 20th century had marked a soft end to their civilization; that what was needed was a rebirth from the ashes of the West. Without understanding this—what they set out to do—we can hardly expect to understand why Yeats’ attempts ended largely in failure, and Pound’s in an embrace of profound evil.

In many ways it is predictable that these men’s work moved them, at least for a time and to a degree, toward fascism. The attempt to rebuild by force a simulacrum of the old world is the perfect political analogue to the modernists’ poetic project. For both the poet and the politician, however, failure is ensured by what Pound, ironically, identified as one of the fatal flaws of the nation of his birth: “the lack in America of any tendency anywhere or in anything; or thinking of anything in relation to any fundamental principle whatsoever; the acceptance of ideas based on forgotten origins, etc., etc.”

Neither Pound nor Mussolini actually thought of anything in relation to any fundamental principle. For both men, tradition was effectively a prop, something to be subjected to the power of the great man, reshaped by his will, and redirected to his ends. This fundamental narcissism of fascist art is illustrated by Mussolini’s own suggestion, quoted by Emil Ludwig, that “[dramatist Luigi] Pirandello writes Fascist plays without meaning to do so! He shows that the world is what we wish to make it, that it is our creation.”

In making a new world for the 20th century, Pound sought to reclaim the vigor of a long-forgotten one without much sincere interest in the forces—primarily Christian—that had shaped it. He professed to seek “the ordering of knowledge so that the next man (or generation) can most readily find the live part of it” without ever finding the live part for himself—or, apparently, looking very hard.

For a contrast we need look no further than Pound’s friend T.S. Eliot, who, like the Rapallo poets, may have flirted with faddish extremism between the wars, but never took the plunge. Eliot’s apparent immunity to the bug of Caesarism is perhaps best explained by his approach to tradition per se, radically different from Pound’s. Arrington quotes Christopher Beach on “Pound’s more idiosyncratic, iconoclastic, and interactive sense of a tradition,” which stands in opposition to Eliot’s belief in tradition as something to which the artist is subject, expressed in his seminal “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” published in the same year as “If I Were Four and Twenty.” For Pound, the genius reigns over tradition; for Eliot, the inverse is true. This divergence is borne out in the lives the two men lived: Eliot a Christian and a monarchist, Pound a fascist and a pagan.

Yeats, meanwhile, occupied a sort of middle ground. In “If I Were Four and Twenty,” the ever-nationalistic poet acknowledges the historical power of Irish Christianity. He even admits the eternal relevance of the Church’s social teaching, that “we discover what is most lasting in ourselves in laboring for old men, for children, for the unborn, for those whom we have not even chosen.” He holds up as a model the great French poet Charles Peguy—then five years dead, shot in the forehead in the first days of the war—whose patriotic sentiments can hardly be divorced from his religious ones. (He admires Peguy in the abstract, but does not seem to recognize the substance and sincerity that undergird the Catholic poet’s greatness.) Yeats speculates that he would, “being but four-and-twenty and a lover of lost causes, memorialize the bishops to open once again that Lough Derg cave of vision once beset by an evil spirit in the form of a longlegged bird with no feathers on its wings.”

It is a bit silly of Yeats to call himself “a lover of lost causes” when he has not so much lost the cause as abandoned it, the cause in question being national religion. Rather than subject himself to tradition—“certainly I am no Catholic and never shall be one;” nor did he even live the Protestantism of his parents—he chose to dwell in absurd fantasies about some noble pre-Christian paganism whose true character he cannot possibly have known. In true modernist fashion, he convinced himself that in doing so he was just moving beyond the guff to the true tradition long since lost to history.

This is the fatal hubris that has stained Pound’s legacy forever and nearly did the same to Yeats himself. In rejecting both the corrupt individualism of the liberals and the corrupt collectivism of the socialists, they opened themselves up to a new force comprising the most malignant elements of both. It took traditionalism—the most powerful and positive form of collectivism—and merely imbued it with the energy of narcissism, enlisting tradition in an aimless and destructive indulgence of the self.

Put more simply: fascism was the ultimate result of an attempt to reap the rewards of tradition without the willingness to submit themselves to tradition. Which is all to say that the problem at Rapallo (and elsewhere) was that Pound and co. were not reactionary enough.

In the last canto completed before his death at 87, the American Sage himself admitted to the failure:

To make Cosmos---

To achieve the possible---

Muss., wrecked for an error,

But the record

the palimpsest---

a little light

in great darkness---

cuniculi---

An old “crank” dead in Virginia.

Unprepared young burdened with records,

The vision of the Madonna

above the cigar butts

and over the portal.

“Have made a mass of laws”

(mucchio di leggi)

Litterae nihil sanantes

Justinian’s,

a tangle of works unfinished.

I have brought the great ball of crystal;

who can lift it?

Can you enter the great acorn of light?

But the beauty is not the madness

Tho’ my errors and wrecks lie about me.

And I am not a demigod,

I cannot make it cohere.