Is the British Empire Largely Misunderstood?

Several years ago, while on a business trip to New Delhi, I remarked to an Indian colleague, a Hindu, on the beauty of his country’s Sansad Bhavan, or Parliament House. “Yes,” he remarked, “though we Indians didn’t design it. It was the British. And Taj Mahal was built by the Muslim Turkic Mughals. None of the best architecture in this country is truly Indian.”

I was a bit shocked by his frank willingness to appreciate his country’s debt to former conquerors. Later, after I noticed a worn copy of P.G. Wodehouse on his office desk, he acknowledged that he and his Indian colleagues all loved British literature above any other. Perhaps, I surmised, imperialism’s legacy is not as black and white as we are often told.

This is the central argument of University of Exeter professor of history Jeremy Black’s new book Imperial Legacies: The British Empire Around the World, which, according to the book jacket, is a “wide-ranging and vigorous assault on political correctness, its language, misuse of the past, and grasping of both present and future.” The imperial legacy of Great Britain is also, in a way, an instructional lesson for the United States, which, much like the British Empire of the early to mid-20th century, is experiencing a slow decline in influence.

As a former history teacher who has visited many former British colonies in Africa and Asia, I’ve been well catechized in how British imperialism is interpreted. The British, so we are told, were violent aggressors and expert political manipulators. Using their technological superiority and command of the seas, they subjugated cultures across the globe, applied the “divide and rule” policy to set ethnic and linguistic groups against one another, extracted resources for profit, and stole cultural artifacts that now collect dust in their museums. Thus, so the story goes, blame for many of the world’s current problems lies squarely at the feet of the British Empire, for which she should still be paying reparations.

Yet, Black notes, “there is sometimes a failure to appreciate the extent to which Britain generally was not the conqueror of native peoples ruling themselves in a democratic fashion, but, instead, overcame other imperial systems, and that the latter themselves rested on conquest.” Take, for example, the Indian subcontinent, which was a disparate collection of kingdoms and competing empires—including Mughals, Sikhs, Afghan Durranis—during the early centuries of British intervention. All of these were plenty brutal and intolerant towards those they subjugated. Moreover, Hinduism promoted not only the oppressive caste system, but also sati, or the ritual of widow burning, in which widows were either volitionally or forcibly placed upon the funeral pyres of their deceased husbands. It was the British who stopped this practice, and others, with such legislation as the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act of 1856, the Female Infanticide Prevention Act of 1870, and the Age of Consent Act of 1891.

Nor has India been able to escape the same imperialist tendencies as the British. Just ask the Sikhs, whose demands to “free Khalistan” have gone unheeded by New Delhi, and who in 1984 suffered great atrocities at the hands of the Indian military and civilian mobs. Or ask Indian Muslims, of whom more than 1,000 died in the 2002 Gujarat riots and who suffer increasing persecution under the ruling Hindu nationalist party BJP. There’s also not a few folks in Kashmir who happen to call the Indians imperialists. One might note here that many of the problems in former European colonies are not solely, or even largely the result of European imperialism, but can be attributed to many other causes, population increase, modernization, and globalization among them. Corruption in some former colonies, including India, is almost certainly higher than it was during British rule.

India is only one such example where the modern narrative ignores both historical and contemporary realities, including, one might add, the fact that India as it now exists is largely a creation of British colonial efforts. It was Britain that united a disparate group of people into a single cohesive unit with a national identity. Indeed, as Black rightly notes, “modern concepts of nationality have generally been employed misleadingly to interpret the policies and politics of the past.”

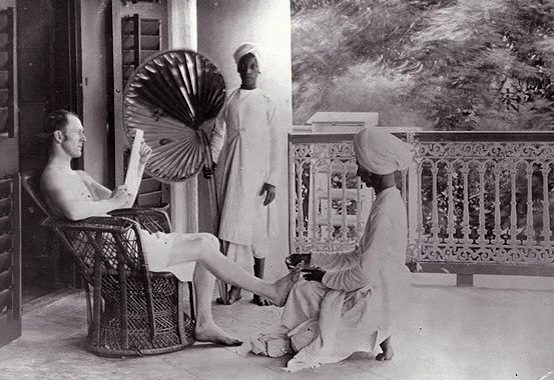

This is further complicated by the fact that in many places, especially India, “alongside hostility, opposition and conflict,” between the imperialists and the colonized, “there was inter-marriage, intermixing, compromise, co-existence, and the process of negotiation that is sometimes referred to as the ‘middle-ground.’” One need look no further than the First and Second World Wars, in which more than 1.5 million and approximately 2.5 million Indians, respectively, fought willingly and bravely in the service of the British crown.

Black notes that “empire was in part supported and defended on the grounds that it provided opportunities for the advance of civilization.” Britain, which was “more liberal, culturally, economically, socially, and politically, than the other major European powers,” was central to ending the slave trade and slavery. British imperialism promised, and to varying degrees secured, rule of law, participatory government, and individual freedoms to many around the world. Imperialism also has a frequent tendency to protect ethnic minorities more than nation-states, because it de facto requires buy-in from everyone, while purist nationalist regimes (e.g. Turkey, Yugoslavia, Burma, Sudan) are often the ones engaged in ethnic cleansing.

Not surprisingly, this more complicated side of imperialism’s legacy is not a particularly popular one in academia or other popular accounts in the media or museums. Black explains:

It can be difficult for those seeking to offer a different view to get their works published, a situation to which I can attest. There is scant attempt by critics to explain why empires arose. There is almost a zeal to suggest that Britain was as bad as the most murderous regimes in history…. Individually, these criticisms largely rest on emotion and hyperbole instead of informed knowledge.

Moreover, it is only within the paradigm of Western modernity that a critique of imperialism is even possible. To borrow from evangelical pastor Douglas Wilson’s commentary on atheist Christopher Hitchens’ criticisms of Christianity, detractors of Western imperialism hijack the ideas of Western civilization and crash them into a ditch.

None of this, Black argues, is to recommend a return to imperialism, or even to apply rose-colored glasses to its legacy. Rather, it is a rebuke to what C.S. Lewis called “chronological snobbery.” Black writes: “to treat these contemporary attitudes to empire…as if Britain, and later the United States, could have been abstracted from the age, and should be judged accordingly, is unhelpful and ahistorical.”

Though one of the aims of Black’s analysis is to inform thinking on the contemporary American “empire,” we should also remember that American suspicion towards imperialism is part of our DNA. We threw off the yoke of the British empire to become an independent nation. From George Washington to strong public opposition to the imperialist motives behind the Spanish-American War, many Americans have censured proclivities to go abroad “in search of monsters to destroy.” Though Black seems to want to provide a more balanced analysis of American power on the global stage, one might just as easily interpret his book as good reason to scale down our international influence, as, like the culturally disintegrating Britain of today, it will not serve our long-term strategic interests.

All the same, we must be wary of, and prepared for, what a retreating America will mean for the world and for our own security and flourishing. Black cites the 2017 Chinese hit film Wolf Warrior 2, in which China intervenes in Africa against European mercenaries and dangerous African rebels. In effect, China, with its “string of pearls” military bases in the Indian Ocean, violations of other nations’ sovereignty in the South China Sea, and “One Belt One Road” economic plan, is already publishing propaganda to defend its role as the next great imperial power.

Critics of European dominance over the world order might ask whether an ascendant China will be a more benign global influence. Given how the communist surveillance state treats its own citizens—including attacking their freedom of speech and religion and brainwashing them in prisons and reeducation camps—I think we already have our answer.

Casey Chalk is a student at the Notre Dame Graduate School of Theology at Christendom College. He covers religion and other issues for The American Conservative.

Comments