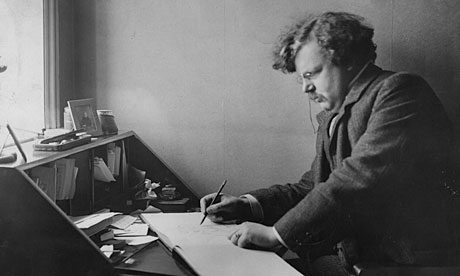

Hope and Humor on G.K. Chesterton’s 146th Birthday

One of my best friends, Paco Olea, died six years ago now. During his last days, while suffering from a painful lung cancer, and years after giving up smoking, when the doctors were no longer betting anything on his lasting a day longer, he started smoking again, enjoying the simple things in life, as if the morphine injections were just part of the landscape.

He never lost his calm, nor his joy. After his death I remembered what he told me, laughing, years ago: “every day when I go to sleep exhausted, I look up at the ceiling and say: thank you God for my bed!” His amusing little prayer reminds me of G.K. Chesterton, who would have been 146 years old today, and who overcame the greatest difficulties of his life thanks to having cultivated a grateful heart capable of detecting beauty in the smallest things, with the eyes of a child. In these times of anxiety and uncertainty, the old English writer has everything we need to keep us afloat: common sense, good humor and discernment.

He was not always an optimist. When he was about 19 the world around him went dark. As incredible as it may seem, young Chesterton tended towards pessimism, one of many skeptical teenagers unable to find beauty in anything. Fascinated by the occult, he got tangled up in the murky world of spiritism, and with no hope in life, his spirits had been mortally wounded. But he had not ceased to be a rebel.

“When I had been for some time in these, the darkest depths of the contemporary pessimism,” he writes in his Autobiography, “I had a strong inward impulse to revolt; to dislodge this incubus or throw off this nightmare.”

“What I meant,” he writes, “whether or not I managed to say it, was this; that no man knows how much he is an optimist, even when he calls himself a pessimist, because he has not really measured the depths of his debt to whatever created him.” Maybe that’s why “I thanked whatever gods might be, not like Swinburne, because no life lived for ever, but because any life lived at all.”

Thus, Chesterton’s gratitude allowed him to skim over the curse of the 19th century art world, to the extent that he was later accused of “optimism” by his critics. Moreover, he himself assures that he dedicated himself to literature to combat the defeatism of his time. Not in vain, a few years earlier, Charles Pierre Baudelaire had reinvented bohemianism in Paris, combining nihilism and decadence with a traumatic childhood past, and laying the foundations for the cursed artists of modern literature.

In his dialectical battle with Bernard Shaw, Chesterton stated: “The decay of society is praised by artists as the decay of a corpse is praised by worms.” Perhaps that is why, with brilliant irony, in the final stages of his life, Chesterton recalled his happy childhood, with no dark ghosts to sell to his audience: “I regret that I have no gloomy and savage father to offer to the public gaze as the true cause of all my tragic heritage; no pale-faced and partially poisoned mother whose suicidal instincts have cursed me with the temptations of the artistic temperament (….) and that I cannot do my duty as a true modern, by cursing everybody who made me whatever I am”.

Alongside this commitment to gratitude, which is intimately linked to his ability to admire small things, Chesterton stood out for his sense of humor, even during the economic hardship he suffered at the beginning of his career. It was not something reserved only for his books and articles. His own physical appearance was often the subject of jokes that he fed himself. He was a big, heavy man, weighing in at around 287 pounds. So much so that, according to his biographers, Wodehouse once used it to describe a very big noise: “a sound like Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin”.

Thus, it is said that during the First World War, a woman asked him why he was not “out at the Front.” He answered: “If you go round to the side, you will see that I am.” Also in the hours he spent debating with his friend Bernard Shaw, it was common for his physical appearance to come out. “To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England,” Chesterton once told him. Shaw’s answer soon came: “To look at you, anyone would think you have caused it.” He liked to live by his own old words: “What embitters the world is not excess of criticism, but an absence of self-criticism.”

In our post-coronavirus days, when some are tempted to call for larger, more restrictive governments with less individual freedom, it is useful to recall Chesterton’s feeble regard for government and the deification of our democratic systems, which he implied are better for what they avoid than for what they give. In the end, he knew that “all government is an ugly necessity.” And that’s because Chesterton loved freedom. As a reminder that we, too, should love it after the nightmare of global confinement we’ve experienced these past months, the author of The Man Who Was Thursday wrote: “The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.”

The defense of freedom occupied much of his famous confrontation with Shaw, who was the leading representative of the Fabian Society, the intellectuals who wanted Britain to become socialist—but not Marxist —by means of a thoroughly planned propaganda assault on education, politics, and law. That foundation inspired the Labour Party years later. Fabians also supported Lenin in the Bolshevik Revolution and backed the Stalinist Popular Front during the Spanish Civil War.

Chesterton, on the other hand, opposed any tyranny with ideals of a freedom that could not be easily prostituted by socialist sellouts: “Every sane man recognizes that unlimited liberty is anarchy, or rather is nonentity. The civic idea of liberty is to give the citizen a province of liberty; a limitation within which a citizen is a king.” And he portrayed fanatics of the dominant skeptical philosophy of the end of the 19th century with amusing precision: “No skeptical philosopher can ask any questions that may not equally be asked by a tired child on a hot afternoon.”

With the transparent malice of a child, he crushed his intellectual opponents with logic and common sense. When supposedly humanitarian theories began prophesying the coming of the apocalypse from world overpopulation, he preferred to confront supporters of birth control with their own mirror: “I might inform those humanitarians who have a nightmare of new and needless babies (for some humanitarians have that sort of horror of humanity) that if the recent decline in the birth-rate were continued for a certain time, it might end in there being no babies at all; which would console them very much.” In this sense, Chesterton was also an apostle of the ordinary, and in a way he predicted something that sounds totally contemporary today: “The most extraordinary thing in the world is an ordinary man and an ordinary woman and their ordinary children.”

As has been pointed out in these pages, our current crisis is not just a health crisis. Like on a beach, the second wave of the pandemic’s drama is the economic one, and it is already breaking upon the shore. Here, too, there is much that Chesterton can teach us. In particular, he can help us weather the perfect storm of fear and uncertainty. It is the hour of hope. “Charity means pardoning what is unpardonable, or it is no virtue at all. Hope means hoping when things are hopeless, or it is no virtue at all,” writes Chesterton in Heretics, “hope means hoping when things are hopeless, or it is no virtue at all. It is, therefore, the hour of true hope”.

Somehow, the drama of the last few months has awakened us from a recurring dream. That strange “climate emergency” declared in December by the UN under the gaze of little girl Greta Thunberg, acting as the high priestess of environmentalism, illustrates the end of an era. The coronavirus has taught us to distinguish between a real emergency and a debatable fiction. Now, as we work hard to rebuild our lives, our work and our nations, we suspect that perhaps we were wasting too much time on artificial debates.

That is why, in the end, Chesterton’s inspiring prose, like a signpost on the lip of the chasm, stands out more than ever to accompany us as we build the future: “When men have come to the edge of a precipice, it is the lover of life who has the spirit to leap backwards, and only the pessimist who continues to believe in progress.”

Itxu Díaz is a Spanish journalist, political satirist and author. He is a contributor to The Daily Beast, The Daily Caller, National Review, The American Conservative, The American Spectator and Diario Las Américas. He is also a columnist for several Spanish magazines and newspapers. Follow him on Twitter at @itxudiaz or visit his website www.itxudiaz.com.

Translated by Joel Dalmau

Comments