Fulton Sheen, Cuba, and the Latin Mass

Human beings have a natural aversion to hierarchy. It can be uncomfortable to acknowledge the primacy of another at the cost of one’s own ego.

Such aversions animate the impulse towards communism, which professes to neutralize levels of prestige and wealth among citizens, uniting all under the shared banner of “worker.” They also animate much of the discomfort some Catholics feel towards the liturgy of the traditional Latin Mass, the architecture of which acknowledges a vast chain of echelons between God and man.

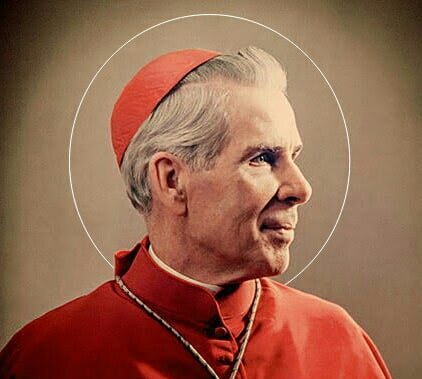

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a masterful observer of human psychology, understood this aversion on a profound level—and he railed against it. He fought against communism in particular. He recalls in his autobiography, for example, how a communist group in New York called him “Public Enemy No. 1.” The FBI later confirmed that his life was indeed in danger, having been targeted by a Soviet spy.

These days, Fulton Sheen is awaiting beatification, having had a miracle in his name approved two years ago this month. The rest of the world, it seems, languishes in his absence. As France celebrates the 232nd anniversary of Bastille Day this month, in observance of the French Revolution dismantling a monarchy run amok, Americans watch with bated breath as Cubans protest against the inhumane living conditions that decades of Communist rule have wrought. Meanwhile, Catholics contend with their own reckoning as they process Pope Francis’s recent apostolic letter hamstringing the traditional Latin Mass, largely seen as the only sector of the Church actively growing. And all of this amidst a global backdrop of floods, plagues, and rising crime.

In many ways, Sheen epitomizes the decadent hierarchical clericalism that rankled the original revolutionaries, both in Cuba and in France, and that rankles those uncomfortable with the traditional Latin Mass today. With a flash of his royal purple ferraiolo, and an impressive array of bling splashed across his cassocked chest, Sheen appeared on primetime each week from a glitzy Manhattan studio to thundering applause. He was the recipient of daily adoring letters. He visited faraway palaces and dined with kings.

His preference for the garb and magnificence appropriate to his rank in the Church relates closely to the style preferences manifested in the Latin Mass, which is frequently decried by its critics for lacy stoles, gilded vestments, thick incense, and a use of silence and shadow that would leave the most astute film-noir buff impressed.

But it isn’t empty drama. Sheen also wrote that “the priest is not his own,” and therein lies the key. The selflessness or lack thereof of a leader can determine the degree of heroic sanctity of a man, the extent of peace among a people, and ultimately a nation’s rise or fall.

In the good archbishop’s case, the sparkling sheen, as it were, masked a solemn core. He approached his role as shepherd with grave seriousness, dying to himself day by day for those entrusted to his care.

In his autobiography he speaks of lying awake at night, shuddering at the consideration of what was expected of him.

“Suppose you had four hundred children and ten were very sick and five were dying,” he once said to a porter who had commented on the apparent glamour of his life. “Would you not worry and stay awake at night? Well, that is my family. It is not as wonderful as you think.”

His profound sense of responsibility for his flock animated his tireless devotion to the mission of disseminating beauty and order. He was fighting to convince a bomb-shelled postwar generation that “life is worth living” as they spiraled dizzyingly into the relativist ethos of the sexual revolution. He preached to the point of exhaustion, requiring surgeries and hospitalization, and collapsing in a radio studio on at least one occasion.

He also made sacrifices in other ways. He allowed himself to be cast, for example, as the “everyman’s” philosopher. He knew that his broadcasts needed to reach people like his own parents: working-class Midwesterners lacking high school degrees. So, he styled himself as competent but basic—to the snootier viewer, an intellectual fop.

This too was a veneer—a thorn lodged directly into the ego for the good of others. In reality, Sheen was an academic heavyweight who dazzled the scholarly community. While at the Catholic University of Leuven (fulfilling an early prophecy made by Bishop John Spalding), he passed his doctorate with the highest distinction possible and became the first American to win the Cardinal Mercier award for his thesis. He declined teaching offers from Columbia and Oxford (obediently following orders to serve instead at an inner-city parish in his hometown of Peoria, Illinois, which he quickly transformed).

And of course, there was that most bitter of crosses to bear, the political squabbling and inside baseball of the New York Archdiocese that Sheen had to constantly navigate and endure in order to tend his flock. His archbishop, Francis Spellman, undermined him at every turn, trying to extort his charity efforts of one million dollars and allegedly driving him off the air. (The drama has followed Sheen even to the grave, with Spellman’s successors waging expensive legal battles to keep Sheen’s body at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and impede beatification efforts. After several failed appeals, the archdiocese was finally forced to release the body in June of 2019, right before the miracle was approved.)

Sheen’s willingness to suffer exhaustion and humiliation for the people in his care—to make of himself a gift—was understated but powerful. And he did it always with a twinkle in his iconic deep-set eyes.

His understanding of his prestige as a gift to others recalls another hero, a Bastille-era figure from literature and film, Sir Percy Blakeney of the Scarlet Pimpernel.

The priest is not his own; nor the sovereign. The character of Percy captures something of this idea in the 1905 novel (and 1982 film version) about an English baronet risking his life to smuggle condemned aristocrats out of Revolutionary France.

On the surface, Percy is not only lavish but dandified and ridiculous. Already prone to a natural appreciation for fashion, culture, and witty conversation (much like Sheen), Percy outdoes himself. He styles himself as the archetype of 18th-century foppishness, to the impugnment of his own reputation. He is written off as silly and air-headed by friends and foes alike.

But like Sheen, Percy is waging a complicated private war on multiple fronts, and his flashy outward appearance, while not totally misaligned with his character, is exaggerated so as to serve as armor. There’s an external battle: He must transgress the French-English border, masterminding new costumes and brilliant escape routes for each trip. And there’s an inward battle too: the battle to maintain courage and virtue in the face of daunting circumstances.

Also like Sheen, he finds himself swimming upstream against a cultural current so mired in materialism and envy that it would choose a bleary uniformity of drabness—that same impulse that motivates all communist revolutions, and, dare I say it, the “spirit of Vatican II”—over the possibility that one citizen might possess greater resources than another. And it would marshal deadly political force to do so.

To outfox such an angry movement—one that punishes people in the public square for their victimhood or, more accurately, their lack thereof—he dashes his reputation and ego. He becomes, like Sheen, outwardly aristocratic, inwardly ascetic. He allows himself to be discounted so that he might save innocent lives from Madame la Guillotine—and he has fun while doing it.

The unrest in Cuba, the dismantling of the traditional Latin Mass, the anniversary of Bastille Day, the French Revolution as dramatized in the Scarlet Pimpernel, and the trials of Fulton Sheen remind us that there are political actors who would sacrifice beauty and order for punitive and hollow idols they’ll call “equality” and “empowerment,” but which are really masks for jealousy, egotism, and self-loathing. And there are religious figures who cast reverence, hierarchy, and royalty as affront to folk sensibilities—even when the royalty in question is that of Christ the King. The best weapon against such forces is the gift of self. Extra points for an offering that masks the blood, sweat, and tears of the Cross with a sparkle in the eye and a veneer of panache.

Perhaps it’s become a platitude: “with great power comes great responsibility.” But men and women actually used to live by that ideal. And in such eras, perhaps hierarchy, whether in governance or religion, wasn’t actually so bad.

Someday Fulton Sheen’s name shall be called “Blessed”—an honorific of one for the blessing of many.

Nora Kenney is deputy director of media relations at a think tank in New York.