Daughters That Turned the Love for Father Into Literary Classics

A quick run-through of father figures in classic American literature reveals a surprisingly small list.

Many heroes or heroines of American literary classics are orphans, raised by grandparents or extended family—Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn quickly come to mind. Others have fathers who are alive but absent, fighting in wars or otherwise removed from the immediate scene. Mr. March from Little Women fits this profile, as does the dad in A Wrinkle in Time.

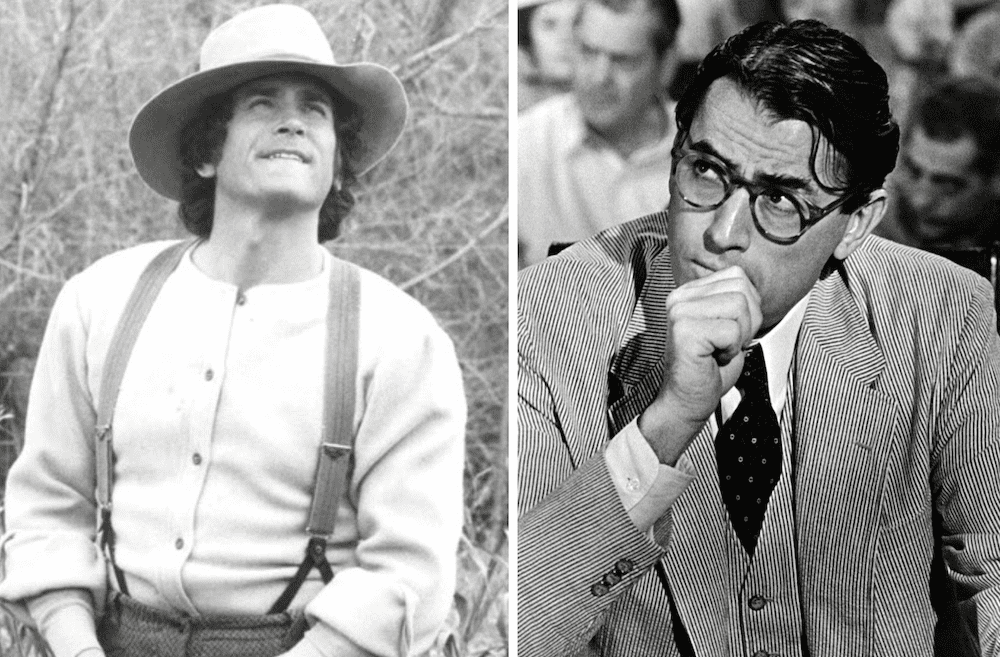

Stand-in father figures abound in works like The Last of the Mohicans, in which Delaware Indian Chingachgook adopts the orphaned Natty Bumppo, creating a meaningful father-son relationship. The fatherhood of these characters, however, is not a central aspect of the storylines. When specifically considering fathers who are front and center in the lives of their families in the classic American literary landscape, the list comes down to Pa Ingalls and Atticus Finch. These two dads are the gold standard of fatherhood in American literature.

The character of Charles Ingalls in the Little House books, referred to as Pa, is based on and named for author Laura Ingalls Wilder’s own father. Pa is the quintessential model father. He tells stories, plays games, and has a great sense of humor. He protects and provides for his family, always placing its needs before his own. Pa is also a fair disciplinarian of his children, expecting them to do exactly as he tells them, which ensures their safety. Pa’s love for his family is never in doubt.

Similarly, Atticus Finch is modeled on To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) author Harper Lee’s own attorney father. The children call him Atticus rather than Dad or Pa, indicating an unusual relationship. He is their only living parent, which means that Scout and Jem must rely on Atticus in ways that children with a living mother would not. They do have a mother figure in Calpurnia, the housekeeper, but Atticus is clearly the main parent. He is not interested in hunting, fishing, or playing sports, things that other fathers do. Instead, he reads the newspaper and practices law. Later, the kids are amazed to learn that their father is one of the best shots in the county when he must take down a rabid dog. The kids didn’t know that their dad could shoot!

Most importantly, Atticus models compassion, kindness, and a sense of justice that applies to all people equally, no matter their class or skin color. These two literary fathers, Charles Ingalls and Atticus Finch, present models of fatherhood in large part because they are created as tributes to great real-life fathers. The love of authors Laura Ingalls Wilder and Harper Lee for their own fathers shapes their literary creations. Pa Ingalls and Atticus Finch may seem to offer unattainable heights for father-children relationships, but their basis in actual people makes their depiction one of realism rather than fantasy.

Readers first meet Pa Ingalls in Laura Ingalls WIlder’s book, Little House in the Big Woods (1932). Wilder’s intention with the book was to preserve her father’s stories for future generations, believing them to be worth saving. These tales are entertaining yet didactic, teaching his young daughters important frontier lessons. Editors at Harper Brothers asked Wilder to expand her narrative with explanations of pioneer life. Pa looms large in these as well, as readers see through Laura’s eyes Pa’s range of skills: from butchering pigs, to smoking meat, to making bullets, to cleaning rifles. Sprinkled throughout these explanations are the Ingalls family experiences of seasonal highlights, for which Pa—often with fiddle in hand—is the center: harvest, Christmas, maple sugaring and its accompanying dance, extended family visits. In subsequent books, as Laura grows up, her relationship with Pa deepens and grows. They are kindred souls.

Laura inherits Pa’s love for adventure and deep-seated need to keep moving west. In On the Shores of Silver Lake, she watches the birds depart and feels that emigrant restlessness before they have even located a homestead in Dakota Territory. “The wings and the golden weather and the tang of frost in the mornings made Laura want to go somewhere. She did not know where. She wanted only to go. . . . ‘Oh Pa, let’s go on west!’” In response, Pa acknowledges his similar yearnings. “‘I know, little Half-Pint. . . You and I want to fly like the birds. But long ago I promised your Ma that you girls should go to school. You can’t go to school and go west. When this town is built there’ll be a school here. I’m going to get a homestead, Laura, and you girls are going to school.’ Laura looked at Ma, and then again at Pa, and she saw that it must happen; Pa would stay on a homestead, and she would go to school.”

Pa sets the example for Laura, making personal sacrifices for the good of the entire family. In that same conversation, Ma attempts to soften the blow by explaining that both Laura and Pa will thank her some day for tying them to civilization. Pa demonstrates for Laura the proper response: “Just so you’re content, Caroline, I’m satisfied.” Wilder as author follows that statement with insight into Pa’s heart: “That was true, but he did want to go west.”

As Laura grows older, Pa must rely on her help with the heavier homesteading chores. He cannot do them alone, and there is no money to hire a farmhand. This reliance on Laura’s help further strengthens their special bond, as does Laura’s deepening appreciation for Pa’s leadership in the newly-formed town of DeSmet. When blizzards block trains from bringing supplies for almost half a year, Pa’s ingenuity at home and guidance among townspeople keeps everyone alive. Laura’s boredom the following winter prompts Pa to create weekly “Literaries,” which not only entertain the townspeople, but provide a platform for Pa’s humor and talent. Throughout the entire Little House series, Wilder pays tribute to the real Charles Ingalls in her portrayal of him as a loving, fair, and inventive father, deserving of respect from his neighbors as well as his children.

In much the same way, Harper Lee depicts Atticus Finch as affectionate, wise, and of the highest character. Lee called her work “a simple love story,” but she did not mean what one would normally think of as a love story. There’s no big romance in To Kill a Mockingbird. Instead, Lee focuses on the love of a father and his two children, and his desire to teach them integrity through his own example. The children daily watch for his return from his law office, running to meet him at the corner post office the moment they catch a glimpse of him. When Atticus takes on a case defending a black man accused of raping a white woman, Scout and Jem are plagued by the taunts of almost everyone in town that their father is partial to African Americans. As far as Scout is concerned, those are fighting words. She and Jem readily defend their father with their fists. Atticus demands that they stop. These insults make for some confusing moments for young Scout, who doesn’t understand why her father’s legal defense of a black man should cause anyone to look askance at her family. During the trial, Jem and Scout sneak into the courtroom and sit in the balcony with the African Americans. When Atticus leaves the building at the end of the trial, Scout is intent on the action on the courtroom floor and oblivious to her surroundings. “Someone was punching me, but I was reluctant to take my eyes from the people below us, and from the image of Atticus’s oily walk down the aisle. ‘Miss Jean Louise?’ I looked around. They were standing. All around us and in the balcony on the opposite wall, the Negroes were getting to their feet. Reverend Sykes’s voice was as distant as Judge Taylor’s: ‘Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passin’.”

The respect shown to Atticus amazes the children, who see him only as their somewhat inept father. When Atticus’ devotion to justice is met by violence directed at his children, he questions his parenting abilities. In the next moment, however, Scout reveals that she has internalized her father’s lessons about compassion and justice. What more could a parent desire than that.

The integrity and good parenting modeled by Pa Ingalls and Atticus Finch stem from the love of novelist daughters for their own fathers, to whom both Laura Ingalls Wilder and Harper Lee penned glorious tributes. In turn, these literary figures based on real fathers serve as fine reminders of what the best fathers bring to their families.

Dedra McDonald Birzer is a lecturer in history and rhetoric at Hillsdale College. This article is a tribute to the model fathers in her own life: her father Ken McDonald and her husband Brad Birzer.

Comments