Chaos and Art

The Lives of Lucian Freud: Fame, 1968-2011 by William Feaver (Knopf: 2021), 587 pages.

Francis Bacon: Revelations by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan (Knopf: 2021), 861 pages.

When abstract art was dominant, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud opposed the prevailing fashion by creating figurative art that conveyed emotional intensity. They were friends at first, but rivalry and jealousy erupted when Freud’s reputation began to match Bacon’s and he could no longer play a subservient role. “When my work started being successful,” Freud declared, “Francis became bitter and bitchy.”

The crucial question about the paintings of Francis Bacon (1909–92) is why so many people were attracted to his theatrical brutality, including images of vomiting and sitting on the toilet, and wanted to look at and even own his monstrous and ghoulish portrayals of cruelty and madness. T.S. Eliot declared, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” But Bacon rubs your face in it. He seems to absorb and express, while allowing his viewers to vicariously experience, the horrors of modern life. Wyndham Lewis brilliantly called him “a Grand Guignol artist: the mouths in his heads are unpleasant places, evil passions make a glittering white mess of the lips.”

More recently, Hilton Kramer zeroed in on Bacon’s aesthetic faults: “We are left, not with a penetrating insight into the agony of the species, but with a mannered and deftly turned style. . . . Not a cry of pain, after all, but a well-composed aria.” Except for Samuel Beckett, there is nothing like hideous kinky Bacon in English literature. He belongs to the tradition of extreme emotions, to Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, Strindberg, and Kafka, who believed “the task of the artist is to make the human being uncomfortable.” Bacon’s main artistic influences were Velázquez’s Pope Innocent V, Grünewald’s Crucifixion, Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Children, and Van Gogh’s expressionist paintings.

Like victims being tortured in a medieval little-ease, Bacon’s open-mouthed, teeth-bared subjects release their rage in primal screams. Their screams originate in the helpless “voice crying in the wilderness” of Isaiah 40:3, the broken spectacles and gaping mouth in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, the cries of fear and pain in horror movies, the agonized horse in Picasso’s Guernica, and the laments in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked.” Edvard Munch’s The Scream exists in a realistic setting and social context. His screamer stands beneath sky and sea, with town and boats in the background, threatening people approaching from behind him on the narrow wooden bridge. Bacon’s less impressive figures are isolated.

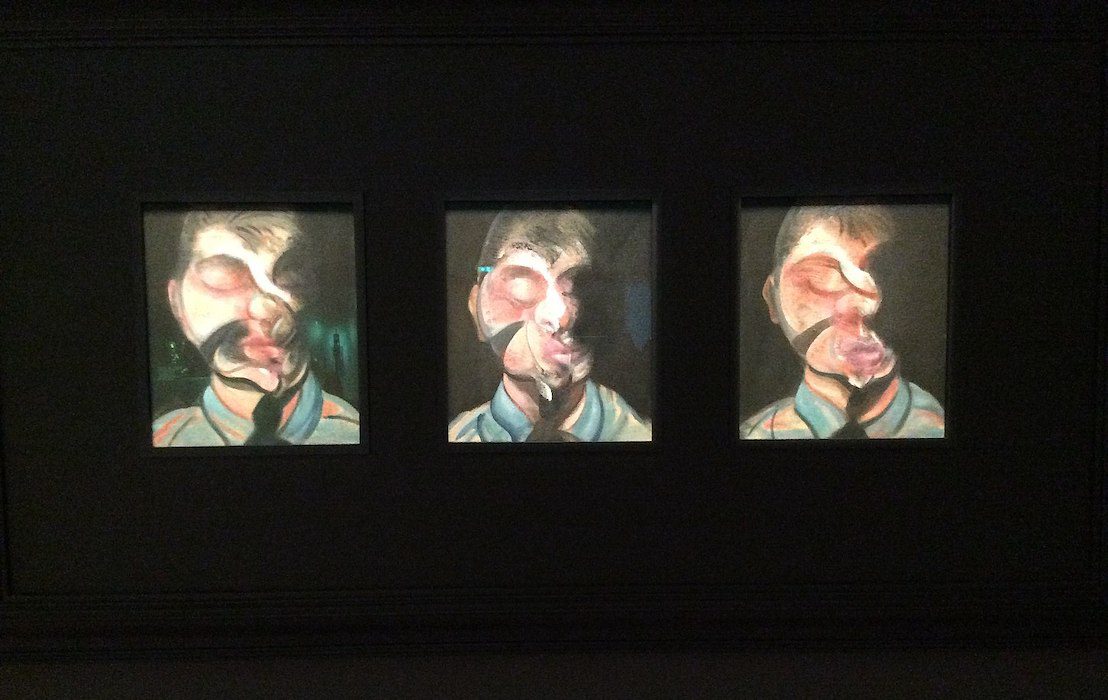

Another puzzling question is why Bacon, retreating from realism, repeatedly smeared the faces of his grotesque creatures. In Robert Browning’s “Andrea del Sarto,” the Renaissance artist laments the desecration of the picture that his wife “smeared/Carelessly passing with your robes afloat!” Bacon’s gruesome distortions are both a caress and an assault, a kind of destruction that makes his creatures seem disfigured by lupus or deformed by war wounds. Bacon thought smeared subjects were more interesting; they are actually more repulsive.

This long biography by Stevens and Swan (a married couple) is thoroughly researched, intelligent and impressive, but the narrative is verbose, sluggish, and burdened by excessive detail. Bacon, an unappealing character, does not come alive until page 225. It’s worth noting that this thick, tightly bound book has narrow inner margins that make it hard to hold open and read. The discussions of the paintings are not linked to the unnumbered illustrations.

The recurrent themes in this biography are Bacon’s breathtaking asthma, restless moves, bursts of inspiration followed by artistic sterility, and massive destruction of his inferior work, as well as heavy drinking and mental breakdowns, abject poverty and lavish wealth, addiction to gambling, and miserable homosexuality. He wore messy makeup, like Gustav von Aschenbach in Death in Venice, and sought rough trade and liked to be whipped. Two of his lovers committed suicide just before his major exhibitions. His nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, lived with him from his childhood to her death in 1951. She topped up her income, as chatelaine of the pissoir, by charging his guests to use it.

The life of Lucian Freud (1922–2011), grandson of Sigmund, also focused on sex and art. A superb realist painter, selfish to the point of cruelty, he attracted and mistreated many adoring young women. During auditions his models were like fillies at the starting gate, racing against odds to gain his attention and become the latest favorite. After he watched a new girl undress, his enchanted prisoner posed in bed and was eager for sex. Many were bohemian art students who wanted to bind themselves to him and bear the child of a genius.

Freud had as many as ten models and lovers at one time. Many others were briefly tried out and rejected as presumptuous or demanding, late or absent, in love with him and no longer needed. These women were given the brush-off in both senses—painted out and discarded. Strangely, no one in his extensive harem ever described Freud as a lover. Did he try to satisfy women or merely please himself? As Arthur Rimbaud heartlessly wrote, “I took Beauty on my knee/I found her bitter so I injured her.”

He had fame, wealth, and influence; paid sitters in cash, cars and flats, interest, bed and babies. He didn’t use contraceptives and like a biblical patriarch scattered his Maker’s image through the land. He didn’t care for or even acknowledge half of his 15 offspring—the others made the cut. He cruelly remarked, “Nothing to do with me that they’re having children.”

Freud wanted and was thrilled by “a dodgy night…an immediate intimate situation with a stranger.” To attract his prey, he used two different ploys: a request to help him find a train ticket in his hotel room or hawkish pouncing to secure promising phone numbers. Escorting young girls in restaurants and clubs made the old man look attractive. Someone suggested he paint Princess Diana but warned she could not be left alone without a bodyguard. The crucial question was always: would they pose naked and expose their genitals? One briefly hesitant model remarked, “It’s nothing, once you get into it.” Another asked, “Do you mind if I keep my boots on?” His models look like exhausted or post-coital wrestlers, but even their toes express character. Freud also used his own children as naked models and possessed what he had created. There was fierce competition among his brood—which extended into the next generation of grandchildren—for his time, attention, portraits, love, and wealth.

William Feaver’s sympathetic and admiring book reveals that “Lucifer” Freud, who was born in Berlin and came to England when he was ten, retained his German accent. He rrrolled his r’s and called the author Vill-yam. Freud is constantly described as vicious, tyrannical and feral, an absolute beast. Malicious and venomous, he’s annoyed when he can’t punish an offender. He severely exclaims, “I don’t get my hanky out” for my victims and “hate upsetting people, unless I mean to.”

Freud, who shared Bacon’s Dostoyevskian obsession with gambling, loved taking risks in racetracks and casinos without taking responsibility for the dire consequences. “The only point of gambling,” he declared, “is to have the fear of losing and when I say losing I mean losing everything. It has to hurt.” He wittily confessed, “If you had what I owe, you’d be a wealthy man.” But when Freud had money, he was always munificent. The New York dealer William Acquavella captured him as a client by paying off his racing debt of $3.5 million. In 2008, one of his paintings was sold to a Russian tycoon for $33.6 million, and he left an estate of £96 million.

Feaver’s unusual, valuable, and fascinating book, his second volume on Freud, is more an oral history than a biography. It is based on tapes and notes recording their long phone and face-to-face conversations, and on their work together arranging Freud’s exhibitions and catalogues, almost every day from 1973 until 2008. “It combines,” Feaver writes, “his words and my recollections together with the reminiscences of many others whose relationships with him differed wildly.” Feaver’s roller-coaster rush of nonstop talk is vivid and revealing but very repetitive, and his chapter titles do not indicate the content or year. He links but does not provide a clear context for Freud’s endless monologues—a 35-year psychoanalytic session. He records but does not evaluate Freud’s speech, so we don’t know if Freud is telling the truth or merely being provocative.

Feaver’s unusual, valuable, and fascinating book, his second volume on Freud, is more an oral history than a biography. It is based on tapes and notes recording their long phone and face-to-face conversations, and on their work together arranging Freud’s exhibitions and catalogues, almost every day from 1973 until 2008. “It combines,” Feaver writes, “his words and my recollections together with the reminiscences of many others whose relationships with him differed wildly.” Feaver’s roller-coaster rush of nonstop talk is vivid and revealing but very repetitive, and his chapter titles do not indicate the content or year. He links but does not provide a clear context for Freud’s endless monologues—a 35-year psychoanalytic session. He records but does not evaluate Freud’s speech, so we don’t know if Freud is telling the truth or merely being provocative.

Sometimes Freud’s meaning is obscure: “Lots of things I can be said to have done in a way I didn’t avoid.” Since Feaver does not identify most of the people he mentions, his book is chaotic and confusing. He should have listed the cast of characters at the beginning, as in a long Russian novel. Feaver also enlivens the book with his own caustic comments about dealers, curators, and critics who disagree with him. His enemies are amusingly punctured as gossipy, ignorant, supercilious, prurient, aggrieved, troubled, waspish, sly, and snakelike.

Feaver briefly describes 250 paintings but reproduces only 32 colored plates, so readers usually don’t see what he’s talking about. He doesn’t explain why Freud painted so slowly and needed 120 hours for his portrait of David Hockney. Freud (I think) took time to mix his colors, did not make preparatory drawings, and plunged right in. He strove for perfection and discarded many pictures. He built up his portraits detail by detail, but often scraped, scrapped, and started again, spreading the waste paint on the swarming studio wall that looked like an abstract picture. Freud called this a “curious, tedious method of painting.”

Freud balanced the chaos of his life with the order of his art. He established his expressionist ambience and mood with deliberate and patient scrutiny, with meticulous care and riveting attention. Like Kafka and Bacon, he wanted to agitate and disturb, to astonish, seduce, and convince, “to make something that’s never been seen before. Personal and fearless.” The wounded models fled the studio, but the vital mixture of sex and art inspired the greatest English painter of the 20th century.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, is the author of Painting and the Novel and Modigliani: A Life.