A Time Of Sonorous Prose

No writer can fully escape the spirit of his own age.

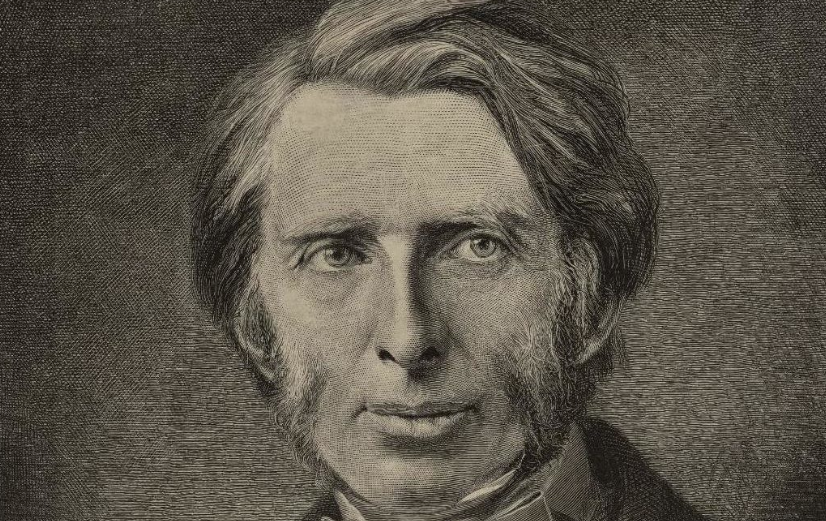

The best writers can write beautifully about anything, even insects. Consider John Ruskin describing fireflies in 1866:

How they shone! through the sunset that faded into thunderous night as I entered Siena three days before, the white edges of the thunderous clouds still lighted from the west, and the openly golden sky calm behind the Gate of Siena’s heart, with its still golden words, ‘Cor magis tibi Sena pandit,’ and the fireflies everywhere in sky and cloud rising and falling, mixed with the lightning, and more intense than the stars.

Sweet-sounding prose about insects doesn’t happen by accident. Compare Ruskin’s firefly reverie to Kafka, writing about about a beetle only five decades later in 1916:

One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that in bed he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug. He lay on his armor-hard back and saw, as he lifted his head up a little, his brown, arched abdomen divided up into rigid bow-like sections.

Even an ardent Kafka fan would have to admit that this prose is not as sonorous as Ruskin’s. One could claim that some beauty is lost in translation. But other translations are just as flat: with Kafka, the dry, unpoetic bleakness itself is the point.

How can we explain the differences between these passages? We could start by analyzing them technically to try to explain the different effects they have on the reader. Ruskin’s exclamation points and classical allusions contrast with Kafka’s dour, matter-of-fact descriptions in objective ways that can be measured and quantified.

But no purely technical analysis provides a satisfying explanation for the differences between Ruskin and Kafka. The differences between them are deeper than prose styles, and come from their distinct views of the universe. Ruskin viewed the universe as wondrous and providentially ordered, and he aimed to inspire joyful awe in his readers, even when writing about something as mundane as insects on the side of the road. Kafka had something like the opposite aim: to show that even potentially awe-inspiring miracles like spontaneous metamorphoses into new species are nothing more than random absurdities perpetrated by an indifferent or even cruel universe. Ruskin aimed to enchant, Kafka aimed to disenchant, and the differences between their prose styles have more to do with these metaphysical aims than with their particular word choices.

The authors’ metaphysical differences represent not only a contrast between two individuals; they attest to the differences between two starkly contrasting eras. Ruskin, a Victorian, imbibed the positive ambition and expansive optimism of his culture, and the high value it placed on aesthetics and beauty. Kafka lived around the beginning of the twentieth century, when people began to earnestly believe that God was dead and science would rule a morally empty cosmos. To some extent, both Ruskin and Kafka were products of their times, with prose styles that were constrained by the beliefs and attitudes that surrounded them. Every age produces its own metaphysics, and, try as he might, no writer or artist can fully escape from the limits of the spirit of his own age.

If Ruskin and Kafka were limited by the spirits of their respective times, it is natural to wonder what kind of limits today’s zeitgeist places on the quality of our own prose. The great Theodore Dalrymple believes that these limits are substantial. In an analysis of the prose of the seventeenth-century moralist Joseph Hall, he wrote: "Hall lived at a time of sonorous prose, prose that merely because of its sonority resonates in our souls; prose of the kind that none of us, because of the time in which we live, could ever equal."

Dalrymple’s claim is remarkable if taken literally. Surely we have dictionaries that contain all of the words Ruskin, Hall, and other great writers of the past used, and it must be possible to string the same words together in the same order that they used, or in some equally sonorous combination. We can use their exact metaphors and allusions if we wish, or similar, equally lovely ones. How could it be that such resonant prose is literally impossible to create in our own time? If we cannot write as beautifully as the great writers of the past, it could not be for any technical reason, since we have all of the words and dictionaries and abilities of past generations. There must be something else preventing us from writing as sonorously as Hall. Something must have happened between Hall’s time and today—and between Ruskin’s time in 1866 and Kafka’s in 1916—some decay in the spirit of the age that has made itself manifest in the decay of every writer’s style.

It is hard to know for certain what changed between 1866 and 1916 that so consequentially altered the spirits of these ages. For some reason, we now lack Ruskin’s sure faith that fireflies are signs of a universe of life-affirming miracles. Instead, we have too much of Kafka’s conviction that every living thing is a disgusting and arbitrary accident. If we are not ourselves touched by awe when we see fireflies, we can never inspire awe in others when describing them. Our beliefs and worldviews and the contours of our inner minds determine the limits of our prose, despite our dictionaries and technical abilities.

When we believe, like Dostoevsky, that every human life is precious, we get literary death scenes that wound our hearts and change us forever. When we believe, like Camus, that life is absurd and pointless, even a mother’s passing or a gruesome murder feel like just another day at the beach. These and thousands of other attitudes and beliefs constitute the spirit of our time, and that decay necessarily changes our art. This would explain Dalrymple’s assertion that the past was a time of sonorous prose, and the present only a shadow. Whatever was lost between 1866 and 1916, it damaged our ability to write beautiful prose, and we haven’t yet gotten it back.

The feeling that the art of our age has decayed from a previous golden age (or at least a better or more sonorous age) is something that many of us feel deep in our bones, even if we cannot prove it conclusively. How many of us, when visiting art museums, linger among the creations of many centuries ago, and shy away from anything created in the last hundred or so years? Many of us feel that the art of the last century tends to evoke nothing at all except negative feelings: coldness, disgust, and ennui of the type that Kafka evokes. The passionate faith of Dostoevsky, the providential optimism of Ruskin, the sonorous moral contemplations of Hall, have given way to the cold intellectualizing of faithless cynics like Camus and Kafka and so many others. Even though there are so many talented people in the world, somehow we don’t get the great prose or great art that we used to.

Nor is this feeling at odds with our understanding of history. The best artistic creations of the past are not evenly distributed across times and places. Surveying the past, we see occasional fits of astonishingly impressive artistic activity, interspersed with centuries without much to report on. It’s easy to suppose, though hard to prove, that the best art is produced most prolifically in ages with the best spirits—in ages where people feel connected to others, positive about the future, and sanguine about the universe’s essential beneficence. If we are not able to produce art that matches previous centuries, it could be because we have lost all of that, even as we have gained technology and GDP. The deficiency of today’s art gives us a tentative glimpse into the spiritual deficiencies of our time.

If we live in a time of weak and ugly rather than sonorous prose, the natural question is how we can get out of it. How can we bring about another time of sonorous prose like the one Dalrymple said Joseph Hall belonged to? We could wait out the clock—if we give it six or seven centuries, maybe another golden age will come along naturally. It’s hard to find a better answer, but it would be wonderful if we could; who wouldn’t want to live in a golden age?

In the world of public policy, arguments about golden ages and the weakness of our current artistic outputs have been most conspicuous with regards to architecture. In 2018, the U.K. convened its Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, which was supposed to make policy suggestions to improve the design and style of new real-estate developments. The final report of this commission noted that “we seem to have lost the art of creating beauty in our built environment.” Like Dalrymple believes that we are no longer in a time of sonorous prose, this commission believed that we are no longer in an age of beautiful architecture. Though the commission had laudable goals, its final recommendations were mostly obvious (more green spaces) or vague (“ask for beauty,” “refuse ugliness,” and “create places not just houses”).

The debates about architecture have been more remarkable on this side of the Atlantic. In the twilight of the Trump administration, President Trump issued an executive order demanding changes in the architecture of federal public buildings. The order stated that government buildings “should uplift and beautify public spaces, inspire the human spirit, ennoble the United States, and command respect from the general public.” It goes on to express “particular regard for traditional and classical architecture,” and in several places strongly and specifically criticizes modernist and brutalist architectural styles, and essentially every style less than a century old. Like the U.K.’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, the order seemed to take seriously the feeling that so many of us have: that artistic productions of recent times are much weaker than the art of the more distant past. Notably, the order’s first paragraph cites the constitution of Siena, the same place where Ruskin sonorously described his fireflies: “The 1309 constitution of the City of Siena required that ‘[w]hoever rules the City must have the beauty of the City as his foremost preoccupation...because it must provide pride, honor, wealth, and growth to the Sienese citizens, as well as pleasure and happiness to visitors from abroad.’”

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Unfortunately for all of us, top-down specific style directives, whether from a commission, an executive order, or the constitution of a charming be-fireflied Italian city, don’t have the power to change the spirit of the time in which we live. One cannot usher in a golden age by fiat. If a U.S. president had issued a similar directive about prose, it might have said that all published prose must be either a direct quotation of John Ruskin or Joseph Hall, or a pastiche imitating their style exactly. This would not be so terrible compared to many of the books that are published today. But it hardly needs to be said that it wouldn’t work. If we are to have good artists and writers today, they must find their own voices, even if they aren’t as sonorous or perfect as what came before. Just as important, we must develop prose and artistic styles that match our own time and its unique needs. Quotation and copying of the past can never be enough.

If we’re ever going to enter another age of sonorous prose, it must happen organically. Parents must teach their children, and teachers their pupils, values and attitudes that together mold a zeitgeist that translates to the creation of the best art. The quest to return the world to an age of sonorous prose could even be a genuine opportunity for the right philanthropist. Instead of donating to short-term gains in little elections, a visionary conservative philanthropist might attempt to bring about what Russell Kirk said was the aim of conservatism: “the regeneration of the spirit and character… the perennial problem of the inner order of the soul...” It may not be possible to do it, but we should at least try to recover the beauty and spirit of ages past, and create for our children a time of sonorous prose again.

Bradford Tuckfield is a data scientist and writer. His personal website can be found here.