A Strange Fish: Alon Nashman’s Hirsch

“Were you always like this? Or did the war do it?” That’s the question Angelica Huston asks her husband in the film, “Enemies, A Love Story” based on the Isaac Bashevis Singer novel, when comes to her looking for help in sorting out his relationships to the two other women he married when he thought she was dead. It’s also a good question to ask about John Hirsch, the impossible genius who ran the Stratford Festival in the early 1980s, and who is the subject of a new one-man show starring Alon Nashman and written by Nashman and Paul Thompson, currently running at the Studio Theatre, called, simply, Hirsch.

As Nashman portrays him, Hirsch had ample reason to turn out both brilliant and tyrannical without the war to spur the former and justify the latter. Pre-war portraits of his mother and maternal grandmother in Hungary give us a glimpse of salons and soirees and of words used both to dazzle and to wound. But this world was not to last. When he was not yet thirteen, he was wrenched from the bosom of his family by the war, fleeing to a feral existence until the end of the war, then a stint in DP camps that was only somewhat less precarious, and a desperate search for a country to take him in that ended in Canada, in Winnipeg. Here, in the frozen and mosquito-infested plains, John Hirsch’s genius finally had room to flower.

One man biographical shows are usually cringe-inducing, both because mimicry gets boring after a while and because they tend toward hagiography. And they don’t tend to have a theatrical arc. But Nashman and Thompson’s love-letter to Hirsch (who died of AIDS in 1989) is never boring, unquestionably avoids hagiography (we certainly see the downside of being – and being directed by – John Hirsch), and even manages to have something of an arc.

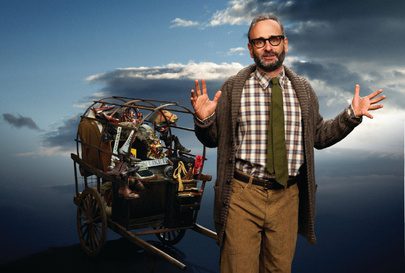

It tells the complete story of Hirsch’s life, from his childhood to his death, but not in chronological order; supertitles help us keep track of where and when we are. It avoids being boring by being consistently theatrical, by keeping up a furious pace (I can’t imagine how exhausted Nashman must be after each performance), and by being about something – namely, about theatre. We see Nashman as Hirsch doing what he does, and we are also seeing it done. He’s not telling war stories about politics or what-have-you – he’s talking about The Tempest, and he’s doing it with Caliban (also played by Nashman, of course) crawling out of a trap; he’s talking about Mother Courage, and he’s doing it while dragging the famous cart (loaded with Hirsch’s own life’s bric-a-brac) around behind him; he’s talking about The Dybbuk and he’s under the huppah.

Hirsch, at one point, even attacks the production he is in, berating Nashman and accusing him of making a travesty of his life – and, moreover, not doing theatre worth watching, of making a difference to anyone’s life with this schtick. And he walks off the stage, leaving Nashman alone. (Needless to say, Nashman is playing both Hirsch and himself throughout the spat.) It’s hilarious – but it’s also dramatically effective, because, again, this is what Hirsch (we understand) would do.

It’s a very funny, moving, and completely engaging show. It made me want to know more about Hirsch, to wish that he’d lived long enough to see his work. But it never made me want to have worked with him.

The war, I came to conclude, didn’t make Hirsch’s genius, and it probably didn’t make him the jerk that he clearly could be. What it gave him was a subject. Over and over again, Nashman’s Hirsch returns to the war, and his wartime experience, as the lens through which he sees the classics. The estate to be sold in The Cherry Orchard is his childhood home in Hungary, ploughed under by the Nazi war machine; his mother owned the bookcase that Gayev gives his comical speech of praise to. When Rosalind flees to the woods, she does what Hirsch did, fleeing after his grandfather was shot in front of his eyes by the fascists that he identified with Duke Frederick’s court. Most movingly, Caliban doesn’t hate Prospero – he loves him, or, rather, he hates him because he loves him. Prospero taught him everything he knows; Prospero is his father, and Caliban hates him the way you hate your father. Hirsch is identifying with both sides of this particular relationship – he’s Prospero, he’s culture, come to Canada to teach the natives what art is; and he’s Caliban, the unformed fish-monster, and Canada took him in, clothed him, taught him their language – and rather than be grateful, he wants to rape her daughters (spiritually) and people the country with Calibans.

If you want to make great art, you need a way in, and the war is a big, big way in to many works of art. Not all – I wouldn’t recommend using it to go into A Doll’s House. But Shakespeare, where primal trauma is always in the background, even in the lightest pieces (notice how A Comedy of Errors begins with a death sentence?) is an especially fertile field to plow this way.

Go see it before Nashman has a mental breakdown playing the part. And take Anne Breslaw with you. Maybe she’ll learn something.

Comments