It’s a story Washington tells itself whenever reality grows uncomfortable: China is about to collapse. The People’s Republic of China (PRC), we are assured, is a brittle, illegitimate regime on the brink of popular revolt. Once it falls, a friendly democratic China will emerge—and America’s ruling class won’t have to change anything that they’ve been doing or thinking about since the end of the Cold War.

That means all the elites’ spending—along with all other forms of elite excess—is irrelevant. In their view, China, a country that is both America’s greatest strategic challenger as well as one of its most important trading partners, is going to implode. It’s a house of cards, they say.

It’s all wishful thinking. Could China collapse? Sure. Any regime could collapse. Is the system in China a house of cards? Maybe. But one could—and probably should—argue that the American financial and political order is also a house of cards, cards that are already teetering.

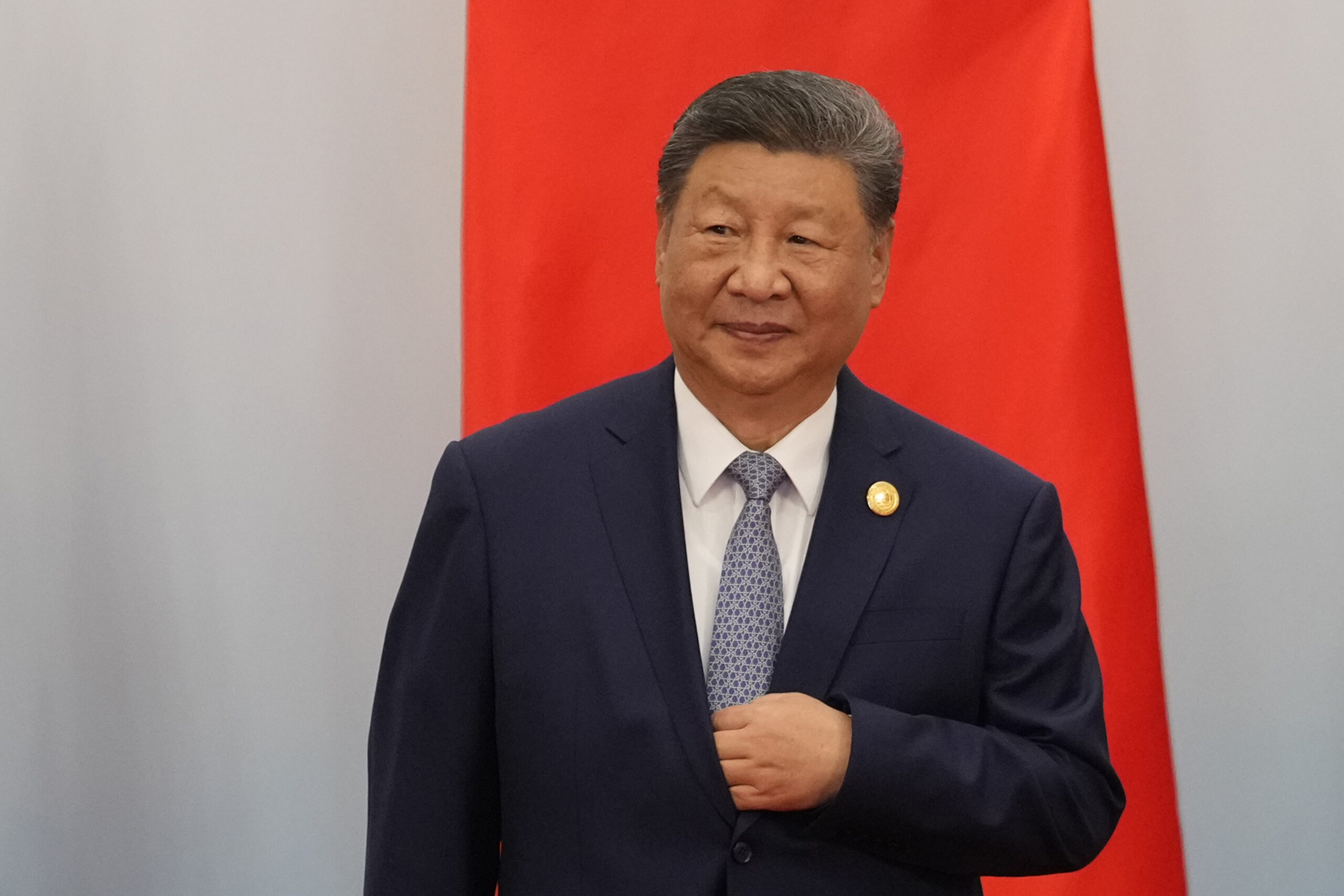

For the last year, the corporate press and their fellow travelers in the Chinese expat community here in the United States have been sharing totally unconfirmed stories about China’s President Xi Jinping having been placed under house arrest. We’ve heard whispers about senior generals in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) revolting. One prominent geopolitical analyst informed me last July that, by the 2025 plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, Xi was going to announce his resignation as part of a secret deal between himself and his rivals (who were set to take power from Xi).

It never happened.

As if that wasn’t enough, when Xi recently directed a massive purge against senior military leaders in the Central Military Commission (CMC), a powerful committee of top People’s Liberation Army (PLA) military officers chaired by Xi himself, the Wall Street Journal depicted it as some form of successful counter-coup led by a reinvigorated Xi against his internal party enemies.

But there was no evidence of any coup to necessitate a counter-coup.

Western intelligence services, such as the CIA, piled on, claiming that the main PLA officer removed by Xi, General Zhang Youxia, was secretly on the CIA’s payroll, providing the American intelligence services with detailed accounting of China’s nuclear weapons capabilities in exchange for gobs of cash.

The only problem with that claim is that Zhang was fabulously wealthy (as were all of the PLA leaders whom Xi purged earlier this year). Zhang and his cohort got wealthy by sitting at the top of the Chinese Communist Party and protecting and supporting Xi Jinping. Given that the punishment of treason is exactly what befell these generals, why would they have risked their futures by risking their wealth and status to feed U.S. intelligence about the state of China’s nuclear arsenal and disposition?

Right after the removal of those older generals, multiple “open-source intelligence” (OSINT) accounts on social media began spewing baseless claims that troops were appearing on the streets of Beijing following the purge of the CMC. The implication was that a potential civil war could erupt at any moment. But these accounts are often tied to larger propaganda pushes in the West, which is why it is important to point out what they have been claiming on social media (and these accounts have massive followings, notably on X).

In case you’re wondering, no civil war has occurred since Xi’s major purges.

But these are the sorts of narratives that pervade Western media, dominate the discourse in the halls of power throughout the West, and shape the perception of Western leaders. (This is why we keep getting China wrong.)

Even as the claims that Xi’s rule was at an end circulated throughout the West, the New York Times published a story revealing that the most recent Pentagon Overmatch Brief found that, if a war over Taiwan erupted, the Chinese military would decisively defeat the U.S. military in a relatively short order.

Clearly, China cannot both be collapsing and have a conventional military that today could rapidly defeat the U.S. military in a fight over the First Island Chain (the region stretching from the Kamchatka Peninsula through Taiwan down to the Philippines). Frankly, I’ll take the Pentagon’s assessment on this one over the flights of fancy our feckless political and media elites are engaging in when it comes to their China analysis.

American elites have embraced what amounts to a strategic coping mechanism because, fundamentally, they understand that the Chinese have caught up to—or even surpassed—the United States in critical ways. The only reason China has achieved this is because of the generous trade policies as well as the strategic ambivalence that American elites have had toward China since the 1970s. In other words, it’s the American establishment’s fault that China is even in the position it is to threaten us, militarily and economically.

This tiresome strategic coping mechanism of the Western elite when it comes to China’s rise could not even hide the fact that China’s economy is doing better than our own, contra the endless heralding of a new American golden age. The Financial Times was forced to admit earlier this year that China’s trade surplus was an astonishing $1.2 trillion in the last quarter of 2025 (even after President Trump subjected China to a grueling trade war).

Cue the rejoinder: “China lies about its figures!” Certainly. Others will say the data coming from China are unreliable for other reasons. But the folks over at the FT know this. Their reporting accounts for these realities. Here’s why the Financial Times used China’s trade surplus figures. Beijing participates in international statistical frameworks promoted by organizations, like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). Their data—notably customs trade data, which is so important for determining trade surpluses—follow broadly accepted definitions and reporting practices. External economists can (and do) audit and compare these global sets, which is how they concluded that China’s trade surplus was so large.

Western elites have spent the last year telling us not to worry about China because Xi is about to be removed from power. When that didn’t happen, they insisted that the purges of the CMC by Xi signaled that China was growing weaker, not stronger (even though Xi removed any potential impediments from the CMC to his rule). Meanwhile, those same voices argue that China’s economy is done—even though their trade surplus went stratospheric last year.

As my former editor at the Asia Times, David P. Goldman, used to constantly remind me: “Don’t worry about what China does wrong. Worry about what they do right.”

With cutthroat alacrity, Beijing has transitioned its economy from a backward, agrarian, North Korea–style cult of personality in the 1970s into a dynamic, vibrant state-capitalist society. In just 50 years, they have gone from being a non-factor in the global economy to the second-largest economy in GDP terms and the largest economy in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), which most economists argue is a superior measurement of economic strength compared to traditional nominal GDP.

What’s more, China today is not animated by the Marxist ideology that the CPC was founded upon. The party’s core legitimizing narrative is national rejuvenation, and the reversal of what Chinese leaders refer to as the “Century of Humiliation.” Even though so many Westerners have said Xi is the closest leader to Mao since Mao, Xi appears to govern less like a Marxist ideologue and more like a civilizational nationalist.

In authoritarian systems, purges rarely signal collapse. They signal that the leader believes he is strong enough to act. That is precisely what you are witnessing with Xi’s ousting of these PLA generals. He is consolidating and expanding his power as he is pressured by his American competitors in a variety of areas. Under these conditions, contrary to the “China is collapsing simply because they’re not Star-Spangled Awesome like the U.S.” narrative, Xi Jinping and China are set to become more powerful and aggressive, not less.

Of course, China is not invincible. It is struggling to transition to a postmodern, high-consumption model economy. As a result, its economy is currently experiencing a downturn. There is an overhang from China’s housing crisis in 2022. There is real demographic decline that threatens future prosperity. Even though you won’t hear it in the media, there is a true youth unemployment crisis.

But how many economic downturns has the United States endured? Why assume China’s regime will implode during a downturn but not the American one under similar conditions?

Especially when China today possesses around 30 percent of all global manufacturing capacity by value. Its dominance in rare-earth refining, battery supply chains, and industrial inputs has ensured that Beijing is already dictating terms to Washington (and the world).

Indeed, China makes the world’s electronics, along with the world’s electric vehicle batteries, solar panels, industrial chemicals, and machine tools. The United States, on the other hand, primarily flips financial assets. In the twenty-first century, manufacturing power is strategic dominance.

A country like China that makes everything rarely collapses suddenly. Financial empires, like the American empire, historically collapse faster than industrial ones. Just ask the British, who effectively abandoned their domestic industry in favor of over-financialization beginning in the mid-19th century, leading to the inevitable collapse of British economic power by the 1960s.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Under these conditions in China, then, a Japanese-style stagnation is plausible. A Soviet-style implosion is highly unlikely.

We should not seek to overestimate Chinese weakness, and we must stop underestimating Chinese resilience. Foreign policy built upon such fantasies leads to the Iraq War. One built on realistic assessments, however, creates strategic opportunities and relatively bloodless victories of the kind we enjoyed in the Cold War.

China’s collapse is not inevitable. Nor is America’s ongoing decline irreversible. Only one of these two outcomes is being taken seriously by the American elite. Getting it wrong means America’s decline becomes inexorable—and China’s rise, however bumpy, becomes unstoppable.