Six Questions for Tara McKelvey on Torture

Tara McKelvey is a features writer at BBC News in Washington. She is the author of Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War. We asked her a few questions about the Senate torture report, Donald Rumsfeld, and her book 10 years after the Abu Ghraib scandal.

1) Have you been following the leaks from the Senate inquiry into CIA

torture of detainees’ post-9/11? What do you make of reports that the CIA lied to the government and the public about the scope and effectiveness of the torture program?

Yes. I’m not sure if I would say “lied.” I don’t think we know enough to say they’ve done that. They have kept a lot of things hidden, and people on the Hill are trying to convince them to say more.

If enough of it is declassified, what will the Senate report tell us?

Who knows. But one thing I’ve wondered about is the interrogation methods that didn’t get approved. The former top lawyer of the CIA said in his memoir, Company Man, that they vetoed one method. Given all that they did, I am wondering what they decided was beyond the pale.

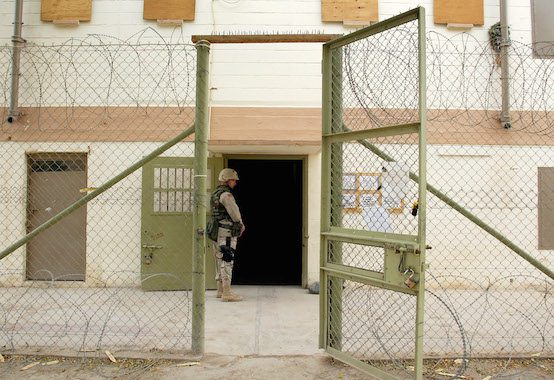

2) We recently marked the ten-year anniversary of the Abu Ghraib scandal. Your goal was to get beyond the frame of the Abu Ghraib photographs, and Monstering provides an account of extreme disarray there: interpreters who weren’t tested on language proficiency, private contractors with sectarian allegiances, a prisoner to guard ratio of 75 to one, soldiers who were told that they could “do whatever they wanted” to the detainees. What was the most surprising thing you learned while reporting the book?

How hard it was to give everyone their due. There is a German writer, Friedrich Hebbel, who once said: “In a good play…. everyone is right.” But when I interviewed Lynndie England, I had to keep reminding myself to give her the benefit of the doubt. A lot of people saw her as a monster, and I didn’t want to do that. Otherwise, I kept telling myself, I would be just like the people at the prison–the ones who didn’t see the detainees as fully human. But she was difficult to talk to–and she was at the prison when terrible things happened, and, anyway, I was surprised how hard that interview was.

3) What is the legacy of the scandal today as the U.S. winds down the War on Terror?

Obama outlawed torture. But years after he promised to close Guantanamo, it is still open. There is a place on the island called Camp 7 that is off-limits to virtually everyone, including journalists. That is where the people are who were once kept in the CIA’s black sites. That is one legacy of the scandal.

4) Monstering also addresses the elite policymakers (John Yoo, et al) who contributed to a climate of systemic abuse at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. You conclude that instead of asking “how could this happen?” the question is really “how could this not have happened?” Several soldiers involved in the scandal, including Lynndie England, were sentenced to time in prison, but so many haven’t been held accountable. What do you make of this?

That it’s not completely surprising, but it still seems wrong. Putting soldiers on trial when they have committed crimes is not a slight against the military, but unfortunately some people think of it that way.

What policy measures have been put in place (by the army if not the CIA) to prevent future abuse?

Most people in the army were horrified by the abuses. They had rules in place before the Iraq war, and they are now making sure that the rules are followed more carefully. The worst abuse was carried out not by people in the military, though, but by people who worked for the CIA. They may have done tons of things to prevent future abuse, but they haven’t really talked about it.

5) Any thoughts on Errol Morris’s new Donald Rumsfeld documentary?

I love Errol Morris. He is my hero. But Rumsfeld is no McNamara. Rumsfeld does not seem to have thought much about what he has done. He comes across not as diabolical, but as a clown.

6) One doesn’t exactly get the sense that the United States has fully grappled with its own panicked overreach in the aftermath of 9/11. (This moment from a recent Sarah Palin speech comes to mind, as does the almost perfunctory display of torture in popular television shows like “Scandal.”) Is it possible that the next president could “reinstate” torture?

Of course. When I give talks about interrogations and torture, people always ask me why I have a problem with it. I understand–I was all for torture right after 9/11. I would have tortured the hijackers myself if they were still alive, and if I had been able to find them. I wasn’t thinking very rationally. Then I started learning about terrorism and I met the people who had been tortured, and I realized how wrong I was–and naïve. Believing in torture means you aren’t looking at the facts on the ground–you are just believing in some kind of fantasy about how to fix the world.

Comments