Moderation in Pursuit of American Dream-ism Is No Vice

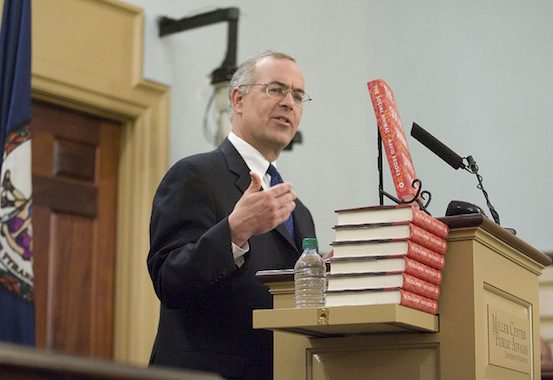

As much as I wanted to give David Brooks a hard time, his column on political “moderation” is a worthy attempt to place the oft-abused term firmly onto its own two feet. Noticeably, Brooks never mentions Edmund Burke, the refuge of most self-identified conservatives who want to play nice with the other team. And he seems to have discarded — or at least muzzled — his old Weekly Standard-era prescriptions for national service and foreign war as a Rooseveltian means of attaining “greatness.”

The first thing he does is dispel the notion that a “moderate” is someone like the late Sen. Arlen Specter or the former Sen. Evan Bayh: “It is not just finding the midpoint between two opposing poles and opportunistically planting yourself there. Only people who know nothing about moderation think it means that.”

He continues: “Moderates start with a political vision, but they get it from history books, not philosophy books. That is, a moderate isn’t ultimately committed to an abstract idea.”

A promising start on both counts. The appeal to history rather than abstract philosophy fits in well with Peter Viereck’s conservative repudiation of “apriorism”: that is, “ideas deduced entirely from ‘prior’ ideas, as opposed to ideas rooted in historical experience.” “Instead,” Brooks writes, a moderate “has a deep reverence for the way people live in her country and the animating principle behind that way of life. In America, moderates revere the fact that we are a nation of immigrants dedicated to the American dream — committed to the idea that each person should be able to work hard and rise.”

This is where things get tricky for the traditionalist conservative. “We are a nation of immigrants dedicated to the American dream” is, I realize, the kind of anodyne statement that offends virtually no one who moves in the mainstream of American politics. But it is nevertheless an abstract idea. It was decidedly not the “animating principle” behind either the Revolution or, a decade later, the Federal Constitution. As Michael Lind observed in The Next American Nation: “Federalists and Anti-Federalists, Unionists and Confederates disagreed about many matters; most, however, shared an understanding of themselves as members of an Anglo-Saxon diaspora in North America.” This consensus was shattered by the creedalism of Lincoln and successive waves of European immigration in the late-19th century and early-20th century. Today’s “nation” — a multicultural mass of people participating in an unstable supranational economy — is a different beast altogether — an empire of money that imports rather than conquers its subjects.

Under these circumstances, it has become extraordinarily difficult to practice the sort of conservatism that Nisbet recommended — a conservatism that abhors the phrase “national community” and works “tirelessly toward the diminution of the centralized, omnicompetent, and unitary state.” Many conservatives have understandably seen in the Obama administration the pretensions of such a state. But behind the president’s sinister-sounding “New Economic Patriotism” is really just a twist on American Dream-ism: “a strong and thriving middle class” whose existence, Obamans believe, depends on a strong activist state to counterbalance the updraft of wealth to the secessionist rich.

The degree of tolerable government activism varies with each school, but there is no disagreement on the ultimate end — that every citizen be equipped to financially and materially “rise.” American Dream-ism is what Obama’s Democrats believe in. It’s what Mitt Romney’s Republicans believe in. Even more than democracy, it’s our civic religion.

As a practical matter, David Brooks’s “moderation” — a politics that accepts tension; acknowledges trade-offs; and modestly cobbles together impermanent solutions — might be the least terrible denomination of it.