How Universities Fail Their Students in Crisis

A student is raped by a classmate, goes to the campus center for help, and is grilled about whether she provoked the rape, told she has to confront her accuser personally in order to be taken seriously, and, ultimately, hounded off of campus, since her post-traumatic stress makes her “unstable.”

You might recognize all the details from The New Republic‘s story about Patrick Henry College’s alleged mishandling of rape cases, but the above incident is drawn from Angie Epifano’s experience at Amherst. Patrick Henry’s Christian ethos informs the tone in which these students were brushed off (you’d be unlikely to hear concerns about purity at a public or secular private school), but the alleged underlying betrayal is more attributable to being a university than a Christian one in particular.

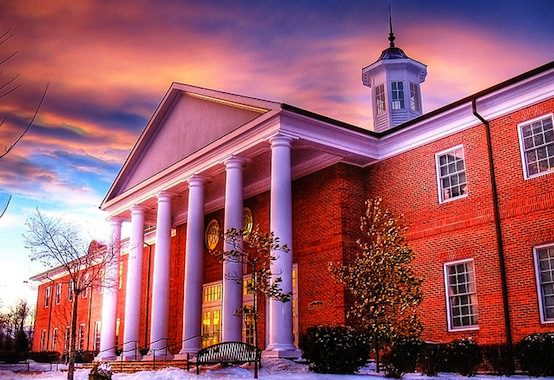

Treating Patrick Henry’s crisis as unique because of its singular status as a private, Christian school (one of only four private colleges in the country that decline federal funds and, thus, aren’t regulated under Title IX) masks a broader problem with administrations’ treatment of students in crisis, one that isn’t limited to sexual assault.

When students at my alma mater discussed the mental health or sexual assault resources, it might have sounded like we were cribbing from the “Never Ever Talk to the Police” lecture by Professor James Duane of the Regent University School of Law that was taking a tour of campuses. You’re talking to someone who’s job is to safeguard the community, not you, if, in their opinion, you present a legal, physical, or reputational risk to the institution.

One of my classmates recently went public in the school paper with one of the samizdat stories we’d been passing around. Like the students at Patrick Henry and Angie at Amherst, Rachel Williams was quickly cross-examined and pushed off campus when she came to the administration for help with self-harm and depression.

And so, when I say “yes” to the ‘I admit cutting myself’ part, he nods his head and closes his eyes like someone has just given him a bonbon. …

“Well the question may not be what will you do at Yale, but if you are returning to Yale. It may well be safer for you to go home. We’re not so concerned about your studies as we are your safety,” he says.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “What makes you think I will be safer away from school, away from my support system?” School was my stimulation, my passion and my reason for getting up in the morning.

“Well the truth is,” he says, “we don’t necessarily think you’ll be safer at home. But we just can’t have you here.”

Rachel’s experience was echoed repeatedly by students on campuses across the United States who were profiled in Newsweek (“Colleges Flunk Mental Health”). Whether schools attribute instability to irresponsibility or a neurological quirk, the reaction is the same: get them off campus before there’s any chance they might harm themseves and open the school up for an in loco parentis lawsuit like the one MIT faced after the on-campus suicide of Elizabeth Shin.

Students who seek help, especially students suffering from mental health issue or the lingering trauma of rape, are rolling the dice that the counselor assigned to them will be willing to take a risk on their recovery, instead of limiting the liability of their school.

Patrick Henry can, and should, be investigated for its alleged past failure, but, to prevent schools from shaking troubled students off like dust from their feet, independent advocates should be involved before a scandal erupts.

Professor Duane’s “Never Ever Talk to the Police” lesson offers some guidance. When you speak to law enforcement, even if you’re the victim, it’s prudent to have a lawyer with you. The cop isn’t only there to serve you, so you want someone on your team who’s looking out exclusively for your interests.

Universities might also benefit from an adversarial system or an independent ombudsman, who reviews and challenges a school’s management of mental health and sexual assault, representing the interests of individual students, not the institution as a whole. After all, as Patrick Henry and others are discovering, their conservative strategies may be putting them, as well as the students they serve, at greater risk.