The Problem With ‘Worldview’ Education

Well, hello! I haven’t been home since June 8, but I got in yesterday from my long peregrinations, and will be headed out again on Monday night. The last place I went was to the Society for Classical Learning conference in Dallas, and boy was it great. I have a lot to tell you about it, but let me start with something that’s big among parts of the conservative Christian world: worldview education. I heard a teacher at a classical Christian school say something interesting about it yesterday, and I wanted to throw it out there for your consideration.

Here, from the Focus On The Family website, is something explaining what is meant by “Christian worldview”:

A worldview is the framework from which we view reality and make sense of life and the world. “[It’s] any ideology, philosophy, theology, movement or religion that provides an overarching approach to understanding God, the world and man’s relations to God and the world,” says David Noebel, author of Understanding the Times.

For example, a 2-year-old believes he’s the center of his world, a secular humanist believes that the material world is all that exists, and a Buddhist believes he can be liberated from suffering by self-purification.

Someone with a biblical worldview believes his primary reason for existence is to love and serve God.

Whether conscious or subconscious, every person has some type of worldview. A personal worldview is a combination of all you believe to be true, and what you believe becomes the driving force behind every emotion, decision and action. Therefore, it affects your response to every area of life: from philosophy to science, theology and anthropology to economics, law, politics, art and social order — everything.

In principle, I see no problem with that. It is true that one’s Christian faith should form one’s entire life. To see the world as a believing Christian is to see it differently from a non-believer, or a believer in another religion, or no religion at all. This is normal. Everybody has a “worldview” in this sense, and Christian worldview educators are right to insist that the teachings of Christianity have consequences for the way we think and live in the world.

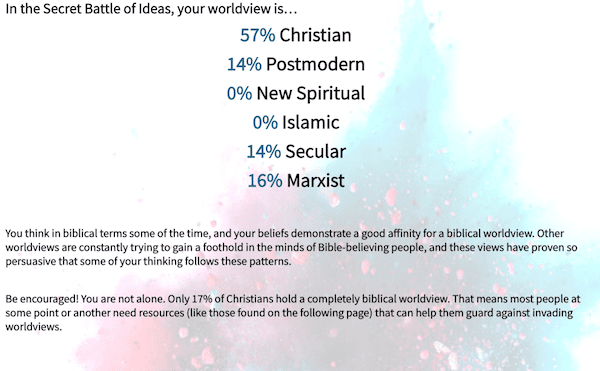

The problems come when you start asking detailed questions, such as, “How much variation within ‘the Christian worldview’ can there be?” I took a “Worldview Check-Up” quiz to test my own orthodoxy. Here’s what it told me:

I suspect that my deviations came partly from answers that reflected my belief that evolution and some level of government involvement in the economy are compatible with Christian belief. Disbelieving evolution comes from a certain interpretation of the Bible. It is also hard to find clear, irrefutable Scriptural support for free-market capitalism. It could well be that capitalism is the best economic system to serve man’s needs, but there are many forms of capitalism, and it is by no means clear that it is “unbiblical” for the state to intervene to assure a more equitable distribution of goods in society.

Also, on a question about what happens when we die, I chose “we don’t know,” not because I don’t believe in heaven and hell (I do), but because as an Orthodox Christian, I do not believe we can presume to speak for God’s judgment. This conflicts with the Evangelical Protestant belief that once you accept Jesus as your personal savior, you are assured of heaven. At least some Evangelicals, as I understand it, believe that one cannot lose one’s salvation — something that Catholics and Orthodox (at least) do not believe. That is, we believe that one always has the possibility of apostasy.

Point is, there is a range of interpretation of some of these issues within Christianity. Some things really are a core part of seeing the world as a Christian. But not others. It is possible for two sincere, Bible-believing Christians to arrive at different conclusions on economic policy, for example. “The Christian worldview” is not entirely synonymous with the worldview of 21st century, middle-class, Protestant Evangelical Americans — or with 21st century American Christians of any sort.

But this particular teacher at the conference focused on something different. He is Joshua Gibbs, who teaches Great Books at the Veritas School in Richmond, Virginia. He spoke yesterday morning about the role of wonder in education. Gibbs talked about how real art is not something that calls forth an immediate response. You have to contemplate it, turn it over in your mind for a while.

“You don’t wonder about what you merely process,” he said.

“Students aren’t formed by analyzing something,” he said. ‘You need to dwell on it for a long time before you have anything to say about it.”

The problem with worldview education, he said, is that it closes off the possibility of wonder by providing a rigid ideological measuring stick for texts. Gibbs said it gives students unearned authority over a book. Hand them “The Communist Manifesto,” they open it up, say, “Marxist!”, then case it aside. Hand them “Thus Spake Zarathustra,” they open it up, see Nietzsche’s name, say, “Nihilist!” — and cast it aside.

Gibbs was not arguing for Marxism on nihilism. He was saying that to truly encounter and wrestle with a great book (even a great bad book!), you have to enter into its world. For example — and this is me saying this, not him — in order to understand where Marxism comes from, you need to put yourself in the place of the man who hears something liberating in, “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains.” Why did Marxism sound plausible and morally righteous to people once upon a time? What does it get right about justice? What does it get wrong? How do we know?

Or take Nietzsche. In one of the most famous passages in his work, he writes:

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

Nietzsche’s point is that in the West, people have ceased to believe in God, and in so doing have destroyed the possibility of moral order. Nietzsche agreed that nihilism was unsustainable, so he devoted himself to constructing a new moral order, one that could survive the end of Christianity.

You don’t have to agree with Nietzsche to recognize that he had some important insights about the catastrophe that had befallen Western man in modernity. His prescription for the illness may be quite wrong, even evil, but his diagnosis was more acute than that of many prominent Christians of his era — and of ours. Nietzsche simply must be grappled with as part of a real education. Because Marx and Nietzsche were two thinkers that made the modern, post-Christian world, Christians have to learn how to deal with them to understand the times, and how a Christian is to live faithfully within them.

If I heard Joshua Gibbs correctly yesterday, he was saying that the worldview model gives a student permission to point to a text, label it, and dismiss it after only a superficial acquaintance with it. This is not real learning; this is sorting our prejudices.

As an aside, I remember encountering Nietzsche in a college philosophy course, one in which I had first been introduced to Kierkegaard. Meeting Kierkegaard was an important step on the road to my own religious conversion, but one of my classmates caught afire with the gospel of Nietzsche. He found “God is dead” to be liberating. Once that semester, he stood on a bench at Free Speech Alley, the weekly campus forum, held high his marked-up copy of The Portable Nietzsche from our class, and proclaimed to the crowd: “God is dead!”

In the next moment, he said, “But if He isn’t” — and he looked skyward, raised his right hand, and made an obscene gesture.

That genuinely shocked me. That made me realize that ideas really do have consequences. I knew that I had to quit sitting on the fence, to quit dancing around Christianity. Either my classmate had done nothing more than pull an outrageous stunt designed to shock, or he had put his immortal soul in danger of hell. I had to judge what he had done, because the fate of my own soul depended on it. Kierkegaard had done his work: I had to choose. Not to choose was to choose, and it was a cowardly refusal of responsibility.

The thing is, if Nietzsche was right, then what that kid did at Free Speech Alley was defensible. But if Nietzsche was wrong, then the fact that many of the students present for the display laughed at it, enjoying the outrageousness and snickering at how offended the Christians were — well, it was frightening.

The point is, Nietzsche has to be confronted. Temporizing won’t do.

I don’t know what happened to Nietzsche Boy, but I do know what happened to me: I eventually became a Christian. I don’t know what the faith commitment our professor had, if any at all, but I do know that he drew all of us deeply into the philosophical texts. For at least some of us in that class, he led us to wonder at these ideas, to wrestle with them, to argue with them and over them, to take them seriously, as having something to do with the way we might live our lives. This is learning! Because I took Kierkegaard seriously, I knew that I had to take Nietzsche seriously — and I knew that none of this was abstract.

Now, I have never been through “worldview” education, so I welcome correction from you who have, and you who provide it. Listening to Gibbs, I understood him to be saying that worldview education closes off students to the possibility of what happened to me, and what happened to Nietzsche Boy. More to the point, it closes us off to the pedagogical role of wonder by giving us instant answers to deep questions.

I wonder, too, how this mode of thinking affects the way one encounters the Bible.

What do you think? You who have a lot of experience in this area, let me hear from you.

And by the way, I’m headed back to Italy on Monday night, this time with my son Lucas. We are going to visit the Tipi Loschi, and then to the Palio di Siena. Posting and comments-approving will be spotty all week. Thanks for your patience.

UPDATE: Hey, readers, remember, I’ve never seen Christian Worldview education. I’m only going on what this classical Christian teacher said about it. I responded as if he were correct. If I — or he — have it wrong about Christian Worldview education, I invite you to explain why. No need to get mad about it. I’m eager to learn.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.