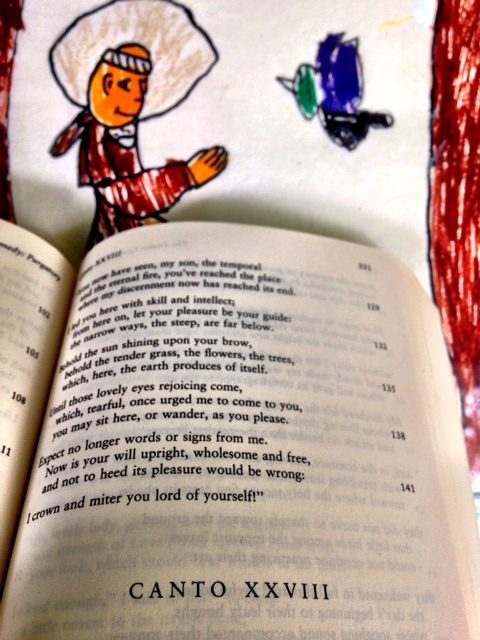

Purgatorio, Canto XXVIII

I warn you, readers: it’s about to get weird on this mountain.

Dante, who began his journey in a terrifying dark wood at the beginning of Inferno, racing about, now finds himself in a very different place, in a very different frame of mind:

By now, although my steps were slow, I found

myself so deep within the ancient wood

I could not see the place where I came in

This is a radical contrast with where the Commedia started — with him lost in a threatening wood, dashing about, scared to death. He is, in fact, in the Garden of Eden. The language Dante uses to describe this place is rich in pastoral imagery. The soft breeze, the joyful birds, the clarity of the water in the stream, the “many-coloured splendors” of the trees, and so forth — this is an earthly paradise.

And then he sees on the other side of the stream, a lady, alone, gathering flowers as she wanders.

“Oh, lovely lady, glowing with the warmth

and strength of Love’s own rays — if I may trust

your look, which should bear witness of the heart —

be kind enough,” I said to her, “to come

a little nearer to the river’s bank,

that I may understand the words you sing.

You bring to mind what Proserpine was like,

and where she was, that day her mother lost her,

and she, in her turn, lost eternal Spring.”

Proserpine is the Roman version of Persephone. What he’s saying, ungallantly, is that she looks like virginal Proserpine did on the day Pluto came out of the underworld, raped her, and dragged her away to be his wife. Proserpine’s mother, Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, searched the world for her daughter. As the lovely lady meets his gaze and draws closer to him, Dante makes a couple more classical references to passion, eros, and tragedy, indicating that he radically misreads the situation. He thinks there is an erotic element at work here — basically, that the woman is coming on to him.

“You’re new here, aren’t you?” she says. Well, she doesn’t put it quite like that, but she gently sets Dante straight. Her name is Matelda, though we won’t find that out in this canto. She tells Dante (and Virgil and Statius, who are still with him) that he’s in the Garden of Eden, the place of innocence and boundless fertility that God made for Adam, but that Adam lost for himself and his descendants through sin. She explains that though things look like the earth here, it’s the earth as it was in its original perfection: an eternal springtime.

What I would have entirely missed here if not for a perceptive essay by Peter S. Hawkins of Yale Divinity School in his collection Dante’s Testaments was this canto’s incredible conversion of Dante’s inner vision. The classical references Dante makes when he first sees Matelda come from the poetry of Ovid, “the premier authority on the Golden Age and the absolute master of woodland romance and seduction.” Dante comes to the banks of this stream with his moral imagination shaped by the pagan poetry of Ovid, which has taught him to associate a pastoral scene like this with eros, passion, and ultimately tragedy — even death.

That was earth. Things are different here. Matelda begins to tell him and his two companions what they’re really seeing by offering them Psalm 92 to “clear away the mists that clouds your minds.”

It’s a psalm of praise to God, speaking of eternal joy and freshness within the shelter of God and his righteousness. Matelda is trying to make Dante re-orient his moral imagination around divine poetry, and the truths disclosed therein. Though the pilgrim has been purified of his sinful dispositions, he still hasn’t learned to see with new eyes. As Hawkins puts it, a lifetime of reading the classics doesn’t leave the memory simply because Dante’s will has been purified. Dante has a history; his habitus cannot be easily eliminated. In other words, his will may have been purified, but his imagination has not yet been fully redeemed.

Matelda tells him that he is now in a realm of original innocence, where, implicitly, fertility does not depend on eros. Robert Hollander says that by telling Dante to interpret what he sees in front of him in the framework of Psalm 92 and its delight, she’s saying that yes, she loves him, but she only loves him not in eros, but with caritas, in God. Here in the earthly Paradise, all love exists purely in God.

According to Hawkins, by proclaiming Psalm 92 to the pilgrims, Matelda is also telling them that God offers to all who accept Him a garden inside their heart in which they can shelter, even in the fallen world. Here, in the earthly paradise, spiritual purity is united to sensual purity, with the world restored to innocence. Remember, in Canto XVII, Virgil told Dante that love is “the seed of every virtue growing in you, and every deed that merits punishment.” Here in Eden, where only virtue exists, love seeds this wild fertility. What’s more, according to Psalm 92, this enclosed garden — a hortus conclusus, which was an important symbol of Marian purity in the Middle Ages — can be cultivated spiritually inside the hearts of those united to God.

In Canto 28, we are presented with the possibility of the redeemed imagination, which first depends on redeemed vision. If he is to progress spiritually, Dante must learn to see with the eyes of innocence. It’s not so much that he must forget Ovid and the vision given him by classical literature as that it must be redeemed too. Matelda tells Dante that the stream that separates them is the river Lethe, which has the power to purify one’s memory by erasing it, a necessary step for living the new life. Later, he will encounter the river Eunoë, which restores the memories of one’s good deeds. You can’t experience Eunoë’s power without first drinking from Lethe, she says. Matelda continues:

Perhaps those poets of long ago who sang

the Age of Gold, its pristine happiness,

were dreaming on Parnassus of this place.

The root of mankind’s tree was guiltless here;

here, in an endless Spring, was every fruit,

such is the nectar praised by all these poets.”

The lady suggests that the ancient poets’ longing for a Golden Age is, in fact, an expression of the ancestral memory of Eden, of our race’s first home. All the poetry that speaks of Arcadia comes from the collective memory of the Paradise we once shared. Ovid and all the classical poets were not entirely deceived, though their moral imagination was fallen. Still, they captured in their art glimmerings of the real world beyond our own. Here in Eden, the dreams of the poets are made innocent again, and fulfilled. Dante’s mental images of the natural world and how to read it are being restored.

You’ll remember the prophetic dream Dante had in his last night sleeping on the holy mountain. Matelda appeared to him as Leah, the first wife of Jacob. She was fertile, and loved the active life. But she was not the woman Jacob most desired. That was Rachel, the contemplative (but barren) sister, who became Jacob’s second wife after seven more years of service to their father, Laban. In the Purgatorio, Matelda represents the active life of the soul. If Matelda is Leah, then who is Rachel, the contemplative life of the soul? We will soon find out.

UPDATE: Still reflecting on this canto this morning, and using it to make sense of some things I’ve been struggling with. It’s made me realize that I had certain expectations about coming back to my hometown, expectations in part predicated on homecoming stories celebrated by our culture — in particular, the story of the Prodigal Son. These stories did not prepare me for what actually happened. In fact, the Prodigal Son story was particularly misleading. A friend points out this morning that the Prodigal Son story is explicitly a story about the Kingdom of God, not a story about this world. It’s the way this world ought to be, not the way things (usually) are. The stories — the parables — the Jesus told are images of Paradise; we are meant to use them as icons to redeem our own imagination.

If the fallen world has corrupted our own imagination, as Matelda indicates, then isn’t it the case that the incorrupt world can at times cause us to read the world falsely, through our hopes? Matelda speaks of the longing of the poets for a Golden Age as being an ancestral memory of Eden — that is, a lost world that can never be fully regained in mortality. I’m thinking that my own nostalgic bent, and my deep and abiding longing for Home, comes from this. Reading and thinking about Canto 28, I’m thinking about how I need to recalibrate my own inner vision. The point is not to become cynical, but rather to educate one’s hope, tempering it with a sense of what is possible in this fallen world, versus what is only really achievable in heaven. To be sure, we can, through grace and by conforming our wills to Christ’s, incarnate heaven in our own hearts and lives to a certain degree; that’s what Dante’s entire pilgrimage is about.

But we will not fully realize the Kingdom of Heaven in this life, and we must be careful about how we allow the images and stories we admit into our imagination to frame our expectations. As I wrote the other day, on Canto XXVII, realizing earlier in my life that I had accepted a false icon of womanhood, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, and turning away from it, was instrumental in the purgation of false images from my own moral imagination, and the purification of my heart. It seems to me that the purification of images is not only about casting out false images and replacing them with true ones, but also to regard the true ones rightly. With regard to the Church, and with regard to matters of family and homecoming, I have been guilty of what Flannery O’Connor warned about: “To expect too much is to have a sentimental view of life and this is a softness that ends in bitterness.”

Isn’t Dante marvelous? This is the highest art, but it is also the realest life. Charles Williams writes, “We have looked everywhere for enlightenment on Dante except in our lives and our love-affairs.”

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.