On Thinking Counter-Revolutionary Thoughts

There’s some really interesting stuff in Eric Mader’s review of The Benedict Option. Mader explains that he has always been on the Christian left. But the advance of same-sex marriage changed things:

How did this revolutionary victory, once realized, affect the culture? Myself I noticed a very tangible shift in the terrain during Obama’s second term. I now attribute it to awareness among liberals and leftists that, with “marriage equality”, the old regime had finally been routed. This meant a new kind of relationship to those like myself who were, on some matters, still part of that old regime. If previously the left could consider me one of them, a somewhat eccentric religious guy whose “heart was in the right place”, suddenly there was a new coldness. In the past it had always been “Well, Eric, you subscribe to a religious interpretation, I don’t”–but our conversation, whatever the subject, would go on. Now any time the discussion, whether face to face or online, got near any part of my Christianity, their point seemed to be that the conversation would not go on. I’d get the equivalent of a scowl, as if even mentioning the Christian tradition was repugnant: all such thinking needed to be finally and utterly pushed out of sight.

I’d always had gay friends, written on gay writers, supported gays and lesbians in their struggles against the anathema conservatives placed on them. I’d always found the bourgeois Christian stigma on sexual sin over the top; it was often cruel and un-Christian–seeming to imply as it did that sexual sin was in a special category that made it worse, even qualitatively different, than sins like pride or greed. I never thought this way myself. But any nuances in my thought made no difference in the new climate. When it became clear to liberal acquaintances that I didn’t agree to their fickle redefinition of marriage, they jumped straight to ostracism. It was not any more that I “disagreed” with them (as I always had on abortion)–no, I had to be made to disappear. Those who held to the old view of marriage were to have no place in our Brave New World. They could be given no place even to speak.

Why such weight put on this particular issue? I’d disagreed with my fellows on the left before, and my right to such disagreement had been recognized. Why now was it suddenly necessary to censor me?

I now see it as related to something Dreher and others have been onto for years. The logic of Enlightenment, the way this logic has been pushed and combined with the Sexual Revolution, has in fact made sexual self-definition the very center of a new cosmology, even a new religion of sorts.

More:

The insults I was getting from my fellow leftists were not far from what these “progressives” dished out to Ms. Stutzman. Which made me realize: Were they actually my fellow leftists in any meaningful sense? Could I in any way work together with people who obviously wanted me in a prison camp?

To interpret such visceral hatred, I now think it useful to focus on the revolution part of Sexual Revolution. We might look at previous political revolutions to get some idea of where we’re at as orthodox Christians. American historian Crane Brinton, in his The Anatomy of Revolution, was one of the first to analyze the stages a revolution goes through.

Revolutions are typically won by a coalition of political actors working together. Once victory is clear, there is often a brief “honeymoon period” where it seems to the victorious classes that anything is possible. For obvious reasons, this euphoria wears off quickly. Because it’s not long before those who backed the revolution realize that life goes on much as before: Utopia has not been established on earth. A growing malaise combines with the fact that the revolutionary leaders are used to living in battle mode, and thus comes the predictable next step. Moderates among the leadership are accused of not being radical enough in their policies–“We must not give in to these backsliders!”–a purge takes place, and the radicals take over. The ambient ardor left over from the initial revolution is then refocused on two new tasks: 1) ensuring ideological purity; 2) mopping up what remains of the defeated classes, who are depicted as all that stands in the way of Utopia’s final arrival. Thus begins the Terror. During this immediately post-revolutionary period, wholly new planks are often introduced into the ruling committee’s platform, typically of a more extremist nature than what was originally demanded in the revolution.

If we view the Sexual Revolution through this lens of past political revolution, it’s pretty clear where we are at present. The revolution has been won, sexual Utopia still hasn’t arrived (because, duh, it never can arrive) and the only thing that might keep our successful revolutionaries busy for the next decade is mopping up what remains of those who refused to drink the Rainbow Kool-Aid when it was first served–i.e. us orthodox religious people. Religious conservatives must be mopped up because, according to the logic, it is our mere existence that prevents Utopia’s final arrival.

This is in fact just how it is playing out in America, in our media and in our courts. Note especially the new plank that was quickly added to the revolutionary platform: the trans movement. There’s really no surprise in the meteoric rise of this raging trans craze. All the revolutionary zeal left over after the victory on marriage–something had to be done with it, no? To keep momentum going, the woke among the liberal intelligentsia had to quick set about destroying the very idea of sexual difference. “Yes, let’s invent thirty new genders and demand citizens use new pronouns. Those who don’t will face fines. Let’s put biological males in teen girls’ locker rooms. See how the rubes like that!”

It’s all both supremely perverse and, and, given where we’re at, depressingly predictable.

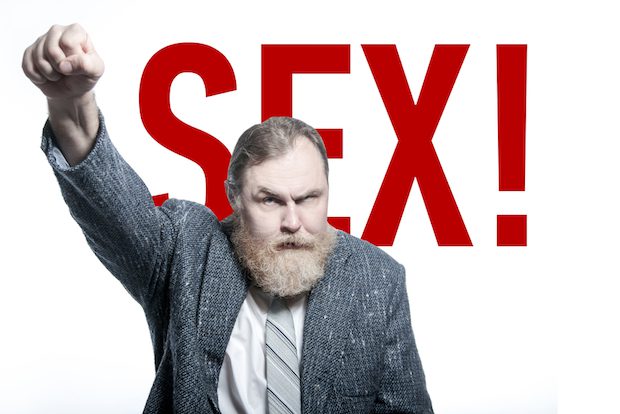

Liberals often accuse Christians of being obsessed with sex, but really there’s nothing like the obsessive focus on sex we see in this new mainstreamed liberalism. The reason for it, again, is the need to make the desiring individual the very center of the Sacred. To balk at a man who demands you refer to him as they or ze rather than he is now a kind of sacrilege. And they want punishment for those who don’t conform. (Cf. the struggles of Canadian psychology professor Jordan Peterson.)

More:

Far too many have seen in Dreher’s project a call to “run for the hills”, to “retreat” from public life; a call to “let the public arena go to hell on its own” while hiding out in the catacombs, as it were. Many of these critics, to read them, seem not to have read the same book I just finished. Their reaction to Dreher’s project might have been understandable before the book was out, but now that the book is on the shelves, I think they might need to take a more careful look at the actual arguments, the double-directedness of the project. On this, Dreher quotes with approval one of the Norcian Benedictines, who speaks of the need to have “borders” behind which we live to nurture our faith, but also the need to “push outwards, infinitely.” This double focus has always been implicit in Dreher’s writing on the Benedict Option, so it’s odd how often it’s missed. Some critics, I suspect, are mainly afraid to face up to what’s happening in America.

Given our decisive rout in the culture wars, you’d think we Christians would step back a bit and ask ourselves if we weren’t doing a few things wrong.

Read the whole thing. It’s one of the better reviews I’ve seen — and Mader’s challenge at the end to think about how the language we use construes our imaginations.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.