Don’t Love Your Job. Love People.

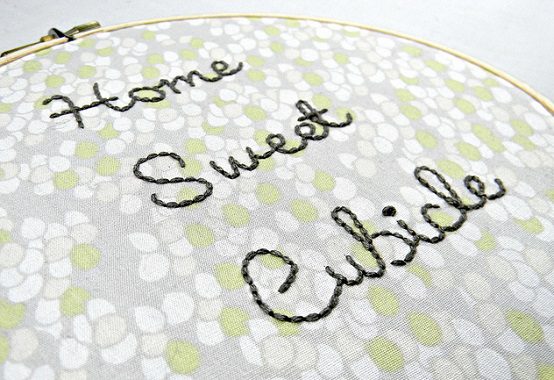

“Do What You Love, Love What You Do,” seems inoffensive enough, at worst an overly peppy aphorism that might hang on the walls of the sort of office to which it is particularly inapplicable. Jacobin magazine, however, sees this aspiration as something darker and more destructive.

According to Miya Tokumitsu, the “Do What You Love” spirit is a way of limiting the power of workers. Those in the lowest paid, least desirable jobs (a migrant worker following harvests, a dishwasher, a janitor, etc.) are implicitly erased from this framing. Those who have managed to secure a spot in the career they care about are told they’ve already succeeded, and there’s little need to quibble over the wages of an adjunct, or the all-night hours of a reporter, since they’re not so petty as to be in this for the money, right?

The unpleasant consequences aren’t limited to the vulnerable groups in Jacobin‘s article, however. Even at the top of the pyramid, Do What You Love, taken to its trendy extreme, does damage. This is the worldview that prompts Silicon Valley companies to offer their employees amenities like laundry, massages, and free dinner, so that their jobs can satisfy more of their needs than just monetary compensation.

Instead of going out into the world and building the rest of their lives, employees are encouraged to find a way to adapt their job in order to meet the rest of their needs. Bosses ask, “What would it take to make you want to stay later and keep working on this?”

These high status jobs start to look like a bizarre update on the company towns of the coal industry. Up and down the hills of coal country, employees used to be paid not in dollars but in company scrip, which was redeemable for goods at the company-run store.

Today’s tech companies sometimes operate according to a similar model. The emotional or social goods that you can’t buy at the luxurious company canteen aren’t worth having—and aren’t purchasable anyway, with the meager time left over after your 60-hour week plus company bus commute.

The trick is getting people to believe that the workplace and the market are big and broad enough to contain your entire life. But love of family, church, or community doesn’t make too much sense translated into these terms. If you love taking care of your child, why not be an entrepreneur and open a child care facility? If you love your church, why not build an app to sell to parishioners to help them do… whatever it is you people do in church?

Employers can only sell us the aspirations they have in stock. Former Wall Street banker Sam Polk, explained in The New York Times how he spiraled into unhappiness when he let his workplace teach him what to desire.

The flashy jobs today might be a little more subtle, offering something a little less obviously hollow than just bigger bonuses, but we should remain skeptical of any job or employer that tells us it can be a worthy inamorata.

Comments