When National Review Turned 15

When William F. Buckley Jr. declared in 1955 that his nascent conservative magazine, National Review, would “stand athwart history, yelling Stop,” he couldn’t have anticipated how that would sound by 1970, when, sporting longer sideburns and a lock of thinning hair flagging dubiously close to his eye, he celebrated his magazine’s 15th anniversary. History, far from stopping, was racing ahead on steroids.

The intervening years had seen President Kennedy gunned down in Dallas, followed by the assassinations of the president’s brother Robert and the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the agony of Vietnam, urban race riots with deaths in the hundreds, the rise of the Baby Boom protest movement, and a revolution in social, cultural, and sexual mores. It was as if a strategic bombing had destroyed the bridge of time, leaving the 1950s suddenly behind, forever.

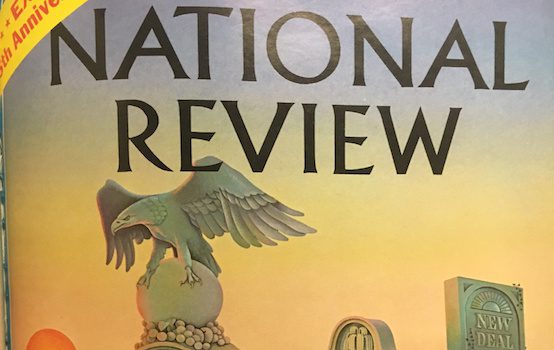

And yet National Review waxed optimistic in its 15th anniversary issue, dated December 1, 1970. The cover boldly declared the death of liberalism in word and picture. Emblazoned at the bottom of the page was the headline, “After Liberalism, What?” The artwork depicted a graveyard filled with tombstones for FDR’s New Deal, Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, JFK’s New Frontier, and LBJ’s Great Society (accompanied by Johnson’s stoic visage). The sun, off to the west, was setting on the American Left.

The tone inside was reflective, cautiously buoyant. For the intellectuals inhabiting the special section of the issue—WFB, Eugene Genovese (Marxist critic of the New Left), James Burnham (ex-Trotskyist, later a leading conservative thinker), Frank S. Meyer (father of fusionism), Charles Frankel, Jeffrey Hart—the battle against liberalism was certainly an existential one. And despite the hopeful cover, that conflict was far from over in 1970. The spirit of the age had internalized many of liberalism’s values, while creating a much more radical movement—the “counter-culture” that now stymied old Lefties on campus as well as the cultural bourgeoisie. “The juice has gone out of liberalism,” despite its heavy hand, which, wrote Burnham, “lies on many of the nation’s organs.”

By way of illustration, he directed a spotlight upon one of the leading liberal intellectuals of the day, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the fastidiously bow-tied gadabout who, as a proud White House adviser to John Kennedy, famously had been tossed fully clothed into Robert and Ethel Kennedy’s swimming pool out in McLean, Virginia. Asked Burnham: “Who would bother pushing Arthur Schlesinger into a swimming pool in 1970?”

As TAC celebrates its own 15th anniversary with this issue, it may be instructive to look back to NR’s similar marker nearly a half-century ago. Much has changed since then, and a lot hasn’t. In 1955, wrote Buckley, the magazine’s focus was on the “centrepetalization of power,” which “threatened to suck all the social energy into Washington, leaving the individual in ineffective control over his own destiny.” Blame was directed at a firmament of New Deal managers and the liberal establishment. The so-called “New Frontier” appeared to the Burkean skeptics populating the early masthead as backdoor statists dressed up in the day’s Madison Avenue trappings. “Triumphant liberalism,” as Frank Meyer called it, easily dominated society, economics, and both political parties. NR emerged as the only acceptable voice of conservative-right opposition to it.

“Conservatism of the 1960s and ’70s was still a fringe, minority movement,” notes 1980s convert Michael Desch, professor of international relations at the University of Notre Dame. “Back then, the political spectrum ran from liberal Democratic to liberal Republican.” Buckley sparked a shift with his upstart periodical, which featured an impressive bench of intellectuals, including Meyer, Burnham, Russell Kirk, and Robert Nisbet.

NR’s 15th anniversary issue makes clear that Buckley & Co. had no illusions about the lingering power of the opposition, even as they warned of liberalism’s rot, accelerated by young Marxist radicals and nihilists—the “New Left”—who were infecting a culture that was increasingly bereft of spiritual and moral sustenance. They were making quick work of the Old Guard, not so much replacing but emasculating it.

But Buckley’s literary legions remained feisty and upbeat. After the disastrous defeat of conservative-libertarian Barry Goldwater in 1964, conservatives brushed themselves off and saw the shellacking as a useful, defining moment. Meyer wrote in the anniversary issue that the GOP, through that defeat, had managed to peel off the “me too” Republicans (we call them RINOs today) before the 1968 campaign. Thus the party had “shifted decisively…to conservative hands.” Richard Nixon won the presidency largely by what Meyer called the new “Middle America,” which was “not class-bound” but values-bound, and included “labor, white-collar workers, middle sectors of society of varied occupation and up to the executive level.”

That was precisely the mix of potential voters Buckley sought to galvanize when he ran for New York City mayor as a gadfly candidate in 1965. He was credited with “sparking much of the controversy and almost all of the humor of the contest,” including his famous reply when asked what he would do if he won: “Demand a recount.” Despite the wry asides and his deeply serious effort to advance creditable policy proposals, he garnered only 13.4 percent of the vote. But just five years later, during NR’s 15th anniversary year, his older brother James captured a U.S. Senate seat from New York as a Conservative Party candidate. Clearly there was a future for conservatism.

♦♦♦

James Buckley’s triumph served as a capstone to a decade the editors looked back on in their typical waggish tone. The magazine noted with some approval the “Periclean words” of John Kennedy on the 1960 presidential campaign trail, but took a dim view of everything that ensued, including the young president’s stumbling performance in the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. By the time the decade ended, another ill-fated Kennedy brother, Robert, was “feasting on the approval of Berkleyite youth, indulgent of Black Power demagogues and conducting pilgrimages to César Chávez.”

Meanwhile, NR loved to rib and mock the “beardy-weirdies” calling for “Kill Your Parents Day,” the stoned-out teens and Black Power activists, armed to the teeth and drawing swoons from the “radical chic” in Manhattan and Hollywood.

When the editors shifted into a graver mode of thought, it was generally to discuss two topics: the global struggle against communism—what Burnham called World War III—and the violence, including a hundred politically motivated bombings by March 1970, perpetuated by the Weather Underground, Black Panthers, and other radical elements, “schooled by Mao, Guevara, Ho, Fanon, Marcuse and (often quite literally) trained by Castro.” NR strongly supported the Vietnam war (though interestingly it did not take up a lot of space in the pages).

Conservatives of that day saw their movement as the crystallization of disparate schools of thought—the traditionalism of Edmund Burke and Russell Kirk, the anti-statist views of Friedrich Hayek, the federalist wisdom of the American Founders, the arch-distaste of Marxist-Leninist ideology, the fears of Soviet expansionism, the “suicidal” tendencies of American liberalism.

Burnham, who wrote Suicide of the West in 1964 (the title was conspicuously cribbed by current NR senior writer Jonah Goldberg for his own 2018 book on the topic), minced no words when he wrote for the magazine’s 1970 anniversary section. He called Charles Manson’s “family,” which had killed the pregnant actress Sharon Tate and friends in a home invasion in 1969, the “perfect, concentrated symbol” of the “anti-family” ideology of American radicals:

Everybody knows that the sex/drug/pornography/incivility/obscenity/self-indulgence subculture is vile and rotten—not least those immersed in it, whose self-degradation and tendency to self-destruction is as obvious in real life as those movies superficially seeming to glorify them…

Liberalism can do nothing to cleanse or halt this Augean wave; can only, in fact, smooth its advance. The secular relativism and permissiveness to which liberalism is committed provides no metaphysical foothold on which a stand might be taken.

This doesn’t differ much from today’s lamentations, including those of TAC’s Rod Dreher, who points out that the vacant liberal ideology “lacks the inner resources to reform itself, precisely because we have become, and are becoming, a people without a shared religion, and therefore without a way to settle our fundamental disputes.” Then and now, it was well understood by conservatives that liberalism has no retraining mechanism to save itself, nor the American culture, from self-destruction.

In 1970, Frank Meyer maintained that the “student revolt is a revolt against the standards of Western Civilization; it is simply a radical speeding up of the glacierlike erosion of those standards by liberalism over the past decades.” One Yalie, class of ’73, remarked to this author that the NR conservatives on campus liked to dress in three-piece suits amid the long-hairs and grungy blue jeans of the day. For their trouble they were knocked to the ground in broad daylight by thugs from the Students for a Democratic Society. Genovese called it “a cult of violence generally manifested in blustering and sporadic and self-defeating acts of nihilism, which are no more than the acting out of adolescent fantasies of revolution by impotent individuals or tiny sects.”

Fast-forward to Antifa, the violent wing of today’s SJW (social justice warriors) movement, attacking not “the pigs” of the establishment nor clean-cut Buckleyites, but enemies of political correctness (which invariably include innocents such as “unwoke” classical liberal professors as well as alt-right peers), on campuses, at civil war monument protests, and outside Trump rallies. To create “safe spaces” for the denizens of the growing number of protected tribal identities, these warriors attempt to enforce speech and behavior codes that make a mockery of the “liberalism” they profess to support. According to young writer Zachary Yost, writing for TAC’s website in February of this year, “under this revolutionary ideology, no dissent can be tolerated. There can be no live and let live—it is all or nothing.”

In a subsequent December 1970 issue of NR provocatively titled “The Bitch Goddess of Individualism,” Richard Wheeler blamed a “new and disturbing” loneliness for the youth attraction to the New Left. They “ache” for community in a world devoid of values, church socials, and “old Yankee certitudes that made companionship so easy for their elders.” In essence, they were “the spiritually wounded.” Not surprisingly, this is a popular theme among today’s TAC writers, again blaming lack of community, and also Facebook and Tinder, for loneliness. Comparing today to the 1950s, Dreher posited in 2018:

We were significantly poorer then, had harder material lives, and had less liberty, and freedom of choice, than we have today. The difference…is that back then we had much stronger social networks. Real social networks, not social media.

Today’s conservatives have no idea how far this “moribund” liberalism will go before it really is part of a cemetery scene like the cover of NR 47 years ago. Like George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead this kind of radicalism tends to live on in a zombie-like state, picking away at societal flesh until someone figures out how to kill it.

♦♦♦

What Buckley and the others couldn’t know in 1970 was that a zombie-killing mechanism would appear in 1980 in the form of Ronald Reagan. After Nixon’s self-abasement, years of citizen demoralization born of acidic cultural dynamics, 58,000 dead in Vietnam, rampant divorce, economic travails of various kinds, and the gutting of tradition through social revolution, the time was ripe. Buckley’s conservative compatriots moved into positions of power theretofore closed to them, and Buckley could boast, “We are the favorite magazine of the next president of the United States.”

As Washington Post writer Henry Allen observed at NR’s quarter-century anniversary:

An era is ending.

Some of the staff worry about how the magazine will cope with the next four years, if not the next 25. After all, their specialty is pointing out that the emperor has no clothes. Now, they’ve got their own emperor.

As far as sense of humor goes, the post-election issue informed its readership that it would be “the last issue in which we shall indulge in levity. Connoisseurs of humor will have to get their yuks elsewhere. We have a nation to run.”

The next 25 years would mark the final success of the magazine’s raison d’être—the fall of communism—and the rise of a political class marked by the radical Baby Boomers who managed to co-opt and thrive in the system they once openly despised. A “Republican revolution” in 1994 led by NR-bred conservatives collapsed under the weight of its own hubris. Shortly thereafter, the 9/11 terror attacks reignited the magazine’s righteous interventionist tendencies, while conservatives rallied around a Republican presidency that expanded the powers of the state in ways not even the disparaged New Dealers had managed to conceive.

Buckley’s magazine had gone from scrappy outsider to conservative elite, says TAC contributor Paul Gottfried, professor emeritus at Elizabethtown College. He adds, “They were very much an establishment publication now.”

It turns out that history, far from “stopping,” has a funny way of re-asserting itself, often as echoes of the past. NR now is part of the establishment and sits atop what has become an industry of conservative media and think tanks spinning out ideas, mass produced for easy consumption. Not surprisingly, today’s traditionalists want something quite different from what this “Conservative Inc.” and the new Old Guard have to offer. Armed with new weapons and the wisdom of the past, these new conservatives are eager to meet the challenge, which of course includes the far-left zombies still lurking in the graveyard.

And so another generation finds itself in much the same situation as Buckley and his followers at the dawn of their magazine in 1955 and 15 years later in the anniversary year of 1970—struggling to reverse history and end an era.

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos is the executive editor of The American Conservative.

Comments