The 19th-Century Election That Predicted the Mueller Mess

The country is polarized. Democrats march in the streets unwilling to accept the legitimacy of the constitutionally elected Republican president whom they insist is a fraud. After all, he lost the popular vote—and by a pretty significant margin.

In Congress, Democrats obstruct the president’s agenda and force an investigation to prove what they already believe—the election was stolen.

However, amidst the angry partisan frenzy, the only hard evidence of corruption points to the Democratic campaign.

That describes the aftermath of the 1876 presidential election, which, similar to the outcome of the 2016 contest, was never quite accepted by a large portion of the public.

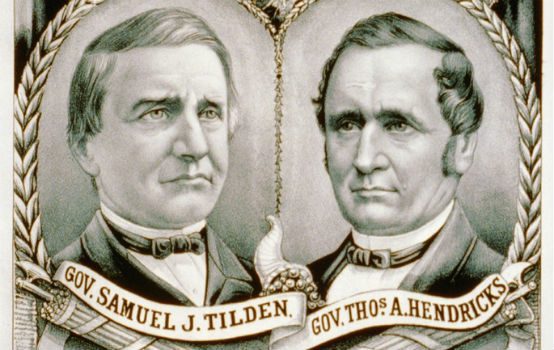

As I detail in my book Tainted by Suspicion: The Secret Deals and Electoral Chaos of Disputed Presidential Elections, in 1878 House Democrats set out to prove corruption by the campaign of President Rutherford B. Hayes, or “Rutherfraud” as they affectionately called him. But the investigative committee eventually boomeranged back on the Democrats when it was discovered that the nephew of Samuel Tilden, Hayes’ Democratic opponent, had been involved in chicanery.

It’s a remarkable parallel with today’s Democrats who set out to prove that President Donald Trump’s campaign colluded with Russians to steal the election from Hillary Clinton. So far, the only actual known collusion—or what might loosely be called collusion—is that the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee bankrolled the Steele dossier, the anti-Trump document that cites as sources “a senior Russian Foreign Ministry figure” and a “top level Russian intelligence officer active inside the Kremlin.”

After election day 1876, electoral votes in Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon were contested. The outcome was decided by a 15-member commission made up of senators, House members, and Supreme Court justices. By an eight-to-seven party line vote, the commission picked Ohio’s Republican governor Hayes, outraging Democrats. Tilden, the New York governor, didn’t write a book called What Happened, but he did proclaim the outcome, “a great fraud, which the American people have not condoned and never will condone—never, never, never.”

Congressman Clarkson Potter of New York, Tilden’s personal friend, led a special committee to investigate the 1876 election. The Potter select committee was formed in the hopes of embarrassing Hayes and maybe even driving him from office. But instead of toppling Hayes, the bombshell from the Potter Committee was a massive plot by Democrats involving attempted bribery and secret codes.

The New York Tribune, a Republican newspaper, published coded telegrams that it had deciphered between Tilden’s nephew, Colonel William T. Pelton, and other Democrats, including Manton Marble, editor of the New York World. The telegrams showed there were attempts to bribe election officials. Pelton lived with his uncle, which made matters look even worse.

The Tribune reported that Democrats offered bribes of $50,000 to electors in Florida, $100,000 to electors in South Carolina, and paid $3,000 in Oregon to ensure support for Tilden. One of the Tribune’s headlines read: “Oregon Fraud: A Full History of the Tilden Plot, How the Democratic Reformer Attempted to Purchase a Majority of the Electoral College—The Cipher Dispatches.” An editorial was headlined “The Secret History of 1876.”

Tribune editor Whitelaw Reid received 33 packages of encoded Democratic telegrams from an anonymous sender. The total number was more than 700 telegrams, according to a report by the National Security Agency that covered a history of encoded communications from 1775 to 1900. The elaborate scheme was run by New York Democrats, but involved operatives in all of the disputed states as well as California.

The NSA historical report said, “This collection of codes and ciphers reflects an amazing quest by energetic Democratic leaders seeking electoral votes: the masks also depict ingenious methods by Democrats for maintaining secret communication.”

Among the published telegrams was one from Marble, whose codename was Moses, and Democratic operative C.W. Wooley, codename Fox, to election officials in the disputed states. The Tribune was able to identify who wrote the telegrams and even publish the original coded messages to avoid questions of accuracy.

That was a green light for Republicans on the Potter Committee to demand that the investigation target corruption by the Tilden campaign—the very opposite of what House Democrats wanted to probe. The majority was unable to push the matter aside.

Before the congressional panel, Pelton and Smith Weed, a Democratic operative from South Carolina, confessed to their parts in the bribery scandal. Pelton said his uncle had expressed fury over the bribery attempt in November 1876. That meant Tilden hadn’t approved of the scheme, though he’d apparently known about it. Marble didn’t admit guilt and claimed he was just sending out warnings that those rascally Republicans were trying to steal the election.

Tilden voluntarily testified to the congressional committee, insisting he’d played no role in the matter. Pounding the table at times, the New York governor who had built his reputation on battling corruption emphatically declared “I had no cipher; I could not read a cipher; I could not translate into a cipher.”

History has never turned up evidence to counter this, so it’s likely Tilden was innocent even if his overzealous supporters were not.

The Potter Committee’s majority Democratic report determined both that Tilden was innocent and that he should have won the election. The Republican minority countered that the Hayes presidency had been vindicated and slammed Democratic chicanery. That’s about the kind of majority-minority divide we’d expect from a select congressional committee today.

Similar to the Tilden scandal, the role of Hillary Clinton’s campaign in the Russian-sourced dossier was indirect enough not to touch the candidate herself. A big difference is that Tilden had a reputation for integrity to lose, while Clinton was struggling against the perception that she was a corrupt politician.

So can the cipher telegram scandal shed any light on what’s next regarding the dirty dossier? Probably not.

But the effect of the centennial election scandal was to wipe out hopes among Democrats that Tilden would come roaring back in 1880, similar to Andrew Jackson’s 1828 rematch against John Quincy Adams after Jackson claimed he was robbed. (Democrats have a proud history of claiming they were robbed after losing presidential races.)

In the end, the cipher telegram scandal was little more than an embarrassment for Democrats. Similarly, the Democrats’ involvement with the shady dossier was embarrassing, but it’s not likely anyone will face any real accountability either. The big question now is what actions Robert Mueller will take.

Fred Lucas is the White House correspondent for the Daily Signal, and author of Tainted by Suspicion: The Secret Deals and Electoral Chaos of Disputed Presidential Elections. The views expressed are solely his own. Title and publications listed are for identification purposes only.

Comments