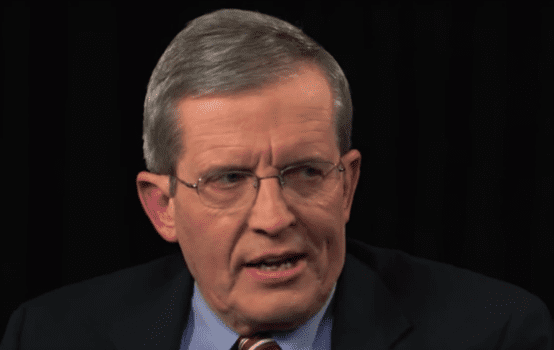

Remembering Jeff Bell: Supply-Side Giant-Slayer

I received a call one day in the spring of 1977—back when I was a young political reporter for The National Observer, a Dow Jones weekly newspaper—from Jeffrey Bell, who the previous year had been a top aide in Ronald Reagan’s unsuccessful campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. We frequently shared gossip and insights on American politics, so I wasn’t surprised by the call. But I was surprised by his opening revelation:

“I’m leaving Washington,” he told me.

“What!” I replied. “Where the hell are you going?”

“I’m moving to New Jersey.”

“What are you going to do up there?”

“I’m going to run for the Senate.”

This was roughly equivalent to my saying I was going to replace Ben Bradlee as editor of The Washington Post. My immediate thought was that my friend was going to the wrong state. How could a Reagan conservative possibly emerge in that liberal bastion?

“Did you consider Idaho?” I asked.

But Bell explained with considerable patience just why New Jersey was precisely where he could make a splash with his particular brand of conservatism. That philosophy was based on his populist insight that ordinary people are perfectly capable of making sound decisions on how to run their lives and didn’t need—and generally didn’t want—government bureaucrats and political elites coopting those decisions. He was particularly passionate about the role of high taxes in thwarting the ability of citizens to guide their own destinies.

A year later, Bell demonstrated his political sagacity by knocking out a sitting senator, Clifford Case, in New Jersey’s Republican primary. Case had entrenched himself in the Senate for four terms—24 years. He had served 12 years in the House before that. Bell hadn’t yet been born when Case was first elected to Congress.

Bell didn’t capture the Senate seat that year. He fell to the powerful personage of Democrat Bill Bradley, the NBA basketball star and Rhodes scholar who had stirred the national imagination, and that of New Jersey, with his athletic wizardry and his solid, earnest demeanor. But by ending Case’s career with a distinctive new political ethos, Bell put himself at the vanguard of a movement that was destined to transform the Republican Party and alter the course of America.

Jeff Bell died unexpectedly last weekend at age 74. He had been pressing his conservative views for decades through a Washington-area think tank he co-founded and through his readiness always to engage in serious discourse with anyone showing the slightest zest for the give-and-take of politics. Though his political passions were out there for all to see, he never showed any agitation or anger in his political discussions, even in exchanges with obdurate opponents. He listened carefully to what others had to say, then unfurled his own considerable arguments with patience and respect. He loved the game.

In recent years he had been concentrating on social issues as a potent leverage point for conservatives in presidential elections. He wrote a book on the subject and identified some 348 electoral votes that could be captured by social conservatives running for president. Four years later a guy named Donald Trump seized a large share of those electoral votes.

But it was Bell’s role in the emergence of “supply-side economics” that cemented his stature in American politics. I rate him among the top four figures in that emergence, along with Jude Wanniski, editorial writer and commentator for The Wall Street Journal; his boss, Robert Bartley, who ran the Journal’s editorial page; Congressman Jack Kemp of New York, at that time famous mostly as a former NFL quarterback for the Buffalo Bills but later highly influential politically; and Bell.

Wanniski, a kinetic figure who operated in a constant state of intensity as if the fate of the world hinged on his latest insight, crafted the argument that America’s growing problem of “stagflation”—economic stagnation mixed with inflation—stemmed from insufficient attention to the supply side of the economy. He sold the idea to Bartley, who turned his editorial page into a kind of journalistic billboard on behalf of this outlier concept. Kemp, reading Wanniski’s Journal editorials (and a particularly influential piece of commentary by him in The National Observer), sought out Wanniski and Bartley with offers to press the cause in Congress. Then Jeff Bell became the first person to test the resonance of the concept on the hustings.

Considering that he was in his 30s, had no prior experience as an office-seeker, had few recent ties to New Jersey, and wasn’t a particularly charismatic figure, he was going to rise or fall on his message. And in that primary his message prevailed.

What was the message? Today supply-side economics is caricatured as simply a parrot-like call for tax cuts, whatever the country’s particular economic ailment might be. This derision isn’t entirely devoid of justification, as some supply-siders do indeed fall back on that simplicity.

But consider the country’s economic situation back in the Jimmy Carter years, when growth stagnated, inflation raged, interest rates spiked, and business confidence plummeted. The top individual tax rate was 70 percent on unearned (generally investment) income and 50 percent on earned income. The corporate tax code was riddled with barriers to commerce. The capital gains tax, pegged at nearly 50 percent in President Nixon’s first year in office, quashed entrepreneurial activity. The top individual rate fostered tax-avoidance schemes and/or a reluctance to pursue serious wealth (which could generate jobs born of economic risk-taking) because the payoff didn’t justify the effort or the risk.

Economic thinking in those days was dominated by the Keynesian argument that the economy was fueled largely by the demand side. Get money into people’s hands, the argument went, and that would generate demand for products. Companies would rush to meet that demand, and the economy would surge ahead.

But what if tax barriers thwarted production and job creation by inhibiting risk-taking, tamping down entrepreneurial zeal, and suppressing corporate investment? In this view, the bottleneck wasn’t lack of demand: the federal government had been pumping that up just fine. The bottleneck was lack of supply, a consequence of government policies (largely tax policies but also regulatory policies, though the Carter administration had begun to address that aspect).

No wonder, the supply-siders argued, there was inflation mixed with stagnation. If inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods, then the government was generating dollars while thwarting the production of goods. Without the goods to sop up those dollars, there would be inflation, and the economy couldn’t grow with a supply-side bottleneck.

Jeff Bell was one of the first people associated with politics to fully grasp both the political and economic force of those arguments. During Ronald Reagan’s 1976 campaign he sought to get his candidate to embrace the supply-side concept fully and blast away on it to the American people. Reagan held back. He wasn’t ready for such a bold new vector in his thinking. He’d ponder it for 1980.

But Bell couldn’t wait that long. He wanted those ideas tested in the political arena, and if nobody else would do it he would do it himself, by moving up to New Jersey and launching what everyone in the state initially considered a quixotically foolhardy campaign against a powerful veteran senator.

Bell told me shortly before he moved to New Jersey (and not long after Carter’s inauguration) that he feared the new president would embrace the supply side notion himself and claim it for the Democratic Party. That would leave Republicans out in the cold on economic policy. This sounds slightly ridiculous today, but back then the latest supply-side experiment had been John Kennedy’s across-the-board tax-cut proposal, enacted into law under Lyndon Johnson. The Democratic Party had not yet ideologically embraced tax increases to pay for its burgeoning government programs (though it was getting pretty close to that).

Wanniski captured the political resonance of all this with his influential Observer piece, in which he posited what he called his “two Santa Claus theory.” The Democratic Santa, he wrote, was well known as the one who provided all kinds of goodies in the form of government largesse—transfer programs, Social Security benefit increases, etc. The Republicans, meanwhile, insisted on fiscal responsibility, which meant they always seemed bent on raising taxes to pay for all those goodies from the Democratic Santa. Thus, in Wanniski’s view, the Republicans had somehow allowed themselves to become Scrooge. No, he argued, the Republican Party should be a Santa party too, giving out goodies in the form of tax cuts designed to juice up the supply side, spur economic growth, and generate jobs. Further, he argued that the expanding economy would also generate extra revenue that would help pay for the Democratic Santa’s abundant gifts.

That last point, of course, generated intense controversy that lingers to this day. There isn’t enough space here for a thorough exploration of that aspect of the issue. But we do know that Reagan, perhaps seeing what Jeff Bell could do with the supply-side issue on the political stump, thoroughly embraced it in 1980, crafted powerfully vivid language to get his points across, and transformed the economic debate in America. That top rate of 70 percent went down to 28 percent, and there can be no doubt that the entrepreneurial passions unleashed in the wake of that policy helped spur the tech revolution that followed. In any event, Reagan generated tremendous economic growth with his supply-side policies, and nobody can argue that those prescriptions lacked political resonance in the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st.

So let it be noted, as we cast a sad eye back upon the remarkable political life of Jeff Bell, that he played a crucial role in demonstrating that resonance—by moving up to New Jersey as a nobody and turning himself into a very effective, but always a very congenial, political giant-slayer. R.I.P.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington, D.C., journalist and publishing executive, is editor of The American Conservative. His latest book, President McKinley: Architect of the American Century, was released in September.

Comments