Raúl Labrador’s Revolt

The House Liberty Caucus isn’t afraid to stir up a revolution in Congress. Its conservative-libertarian members include well-known “troublemakers” like Rep. Justin Amash of Michigan, one of 12 Republicans to oppose House Speaker John Boehner’s reelection in January 2013. Amash, chairman of the Liberty Caucus, warned at the time that a “larger rebellion” could take place in the future—and this April, National Journal reported that as many as 40 or 50 dissident House Republicans have now committed verbally to electing a new speaker.

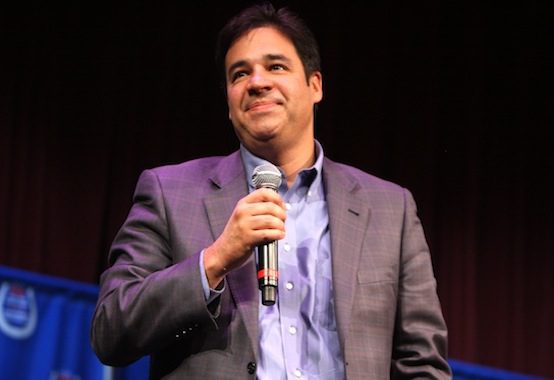

This Tea Party vanguard has yet to put forward a contender to replace Boehner. But the kind of legislator they have in mind is suggested by the man Amash himself voted for as speaker in 2013: Idaho Rep. Raúl Labrador. Amash told Buzzfeed reporter Kate Nocera that Labrador is “the kind of guy who would make a good leader in our party,” and he “would vote for him for speaker again.”

So who is this Idaho congressman?

Raised in Carolina, Puerto Rico by a single mother, Labrador worked his way from poverty to law school and from the state legislature to Congress. Though she lost her job when her son was born, Labrador’s mother Ana Pastor refused to turn to welfare. She told Labrador government dependency led to a “decay of the soul.” She was a Democrat and saw JFK as her hero—but during the 1980s, she switched parties to vote for Ronald Reagan. Her son took note and now cites Reagan as his political role model.

“He made us feel safe,” Labrador says. “There was an assurance in his gaze and a steadiness in his leadership that made America feel better about itself, and I think, more than anything, that’s what he did for me.”

Pastor and her son moved to Las Vegas in 1980. After high school, Labrador enrolled at Brigham Young University, where he met future wife Rebecca Johnson, and thereafter earned his law degree from the University of Washington. Labrador and his wife moved to her native state, Idaho, in 1996, and Labrador set up a law practice in 2000 specializing in immigration.

In 2003, Labrador spoke to Latino voters in Boise and caught the attention of former Idaho House Minority Leader Wendy Jaquet. Afterwards, reports Kip Hill of the local Spokesman Review, she asked Labrador whether he’d be interested in running for office as a Democrat. He laughed and told her, “No, no, I’m a conservative Republican.”

“It wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last, that the political establishment would be surprised by Labrador,” notes Hill.

Labrador won a state legislature seat in 2006 and quickly made waves in the capitol. He organized group discussions with freshman legislators about taxes and other pending issues. In his biggest move, he successfully challenged Republican Governor Butch Otter’s plan to raise taxes to fund roads and bridges.

“I realized I had certain abilities and certain gifts—persuasion and others—that allowed me to be pretty good at this game,” Labrador says.

♦♦♦

Idaho’s first district is, in Labrador’s words, “an interesting district.” In presidential contests, it’s always Republican. But the district stretches across the entire west side of the state: a long, thin swath of ideological and partisan variations. One thing unites it, according to Labrador: “It’s a very independent district.” He says his constituents don’t bother voting along partisan lines—“they just want fiercely independent people.”

When Labrador decided to run for Congress in 2010, no one thought a win would be possible. Walt Minnick, the incumbent, was a rather conservative Democrat: he even received a Tea Party Express endorsement. He was well known in the business community and liked by his district. Many other politicians who imagined themselves “next in line” for the seat, says Labrador, thought Minnick unbeatable.

Instead of backing Labrador, the GOP establishment endorsed another candidate in the party’s primary: former CIA officer and military veteran Vaughn Ward. He received a high-profile endorsement from Sarah Palin and was named one of the first candidates in the National Republican Congressional Committee’s Young Guns recruiting program. But Ward began to make careless and embarrassing errors: during a televised debate with Labrador, he said his opponents’ home territory of Puerto Rico was another country. He was caught plagiarizing policy positions from other politicians’ websites. He even plagiarized Obama’s Democratic National Convention speech from 2004.

Meanwhile, Labrador had amassed a sizeable grassroots team. Former Idaho Speaker of the House Lawerence Denney became one of his campaign co-chairs, “which at the time was not a popular thing to do,” Denney says. Labrador’s team believed the race would be close—but they won by a surprising nine points.

“He came from virtual obscurity in 2010 to win his primary,” says Dan Popkey, political reporter and columnist for the Idaho Statesman. Despite his opposition to the governor’s tax plan, Labrador was still a virtual unknown, and he didn’t begin campaigning for the primary until December.

Looking back, Labrador says he was “lucky” not to be backed by the establishment: he didn’t have the money to pay consultants and so “had to figure out for myself what I believed.” This independence enabled him to present a consistent, personal platform—“I wasn’t just saying these trite or proven phrases that were supposed to persuade people.”

While running against Minnick, Labrador adopted a simple “mantra”: he conceded that Minnick voted like a conservative, but reminded voters that the Democrat was merely representing his district rather than adhering to principles he believed in. “With me,” Labrador said, “you get someone who votes his district and actually believes like his district.” Labrador won by 10 points.

♦♦♦

Today Labrador sees himself as one of a “core group of conservatives” who are bringing change to Congress. He describes them as young and independent, “conservative-leaning-libertarian types,” all willing to defy the establishment in an effort to get things done. One might reasonably assume that Sen. Mike Lee, Congressman Amash, and many from the Liberty Caucus fit within this cohort.

Labrador was an ally of the Senate’s Gang of Eight—legislators from both parties in favor of comprehensive immigration reform—and his ethnic background and work as an immigration lawyer have lent him credence as one of the House’s experts on immigration. His district gives him insight into the tension inherent in the immigration debate as well: Idaho has a sizeable population of immigrants who work—legally or not—at businesses throughout the state. “I saw the needs [of] the agricultural community, the farming community, the construction community … but at the same time I lived in communities that were concerned about the lack of following the law,” Labrador says.

But Labrador left the House’s Gang of Eight last year, citing disagreement over language in the reform bill that would provide health insurance, at taxpayer expense, to undocumented immigrants. “The Democratic Party believes that health insurance is a social responsibility of the nation,” Labrador told The Hill. “I believe that health insurance is an individual responsibility. And that’s a really hard philosophy to mesh.”

Political analyst W. James Antle III of The Daily Caller News Foundation doesn’t believe this hurt Labrador’s standing within the GOP. He suggests that “bailing on the Gang of Eight gives [Labrador] credibility with Republicans on this issue that John McCain, Marco Rubio, and even Paul Ryan don’t have.”

Labrador thinks it would be a “disaster” to pass comprehensive immigration reform this year. He believes the GOP can take back the Senate in November, but if a liberal immigration bill is passed before then, “our base will be depressed in the general election, and we won’t be able to win.”

Though not well known for his foreign-policy stances, Labrador generally aligns with Amash and others in the Liberty Caucus against foreign interventions. He has opposed the National Defense Authorization Act and the PATRIOT Act on civil libertarian grounds. Labrador was also one of 19 House representatives to vote against the Ukraine Support Act in March.

Last September, Labrador announced he would vote against any Congressional authorization for the use of force in Syria. On Sept. 16, he released a statement noting the lack of U.S. national interests at stake, adding, “After our experience in Iraq, I couldn’t think of anything worse than putting our brave service members in harm’s way to police a civil war in a place where we have no vital national interests.”

His maverick inclinations have earned him respect across the aisle as well as among Tea Party Republicans. “I get along with Democrats really well,” he says, “And I think that’s something that’s unreported. I think it’s partly my libertarian tendencies.” He’s currently working on bipartisan prison reform legislation.

♦♦♦

But in order to become a power player in Washington politics, Justin Vaughn, assistant professor of political science at Boise State University, believes Labrador would have to lose some of his fierce independence. Since he didn’t emerge from a “machine-style background, rising up through the ranks and paying your dues,” Labrador has never had to compromise on his ideological principles. “He doesn’t have the incentives right now—nothing that’s coercing him into being more pragmatic,” Vaughn says. Were he to pursue a leadership role in the House, this would have to change.

But the congressman downplays speculation about his ambitions within the Beltway: “I know I don’t want to be here forever,” he says. “I didn’t come to Congress to make it a career.” Indeed, with his children still in school, Labrador goes home to Idaho every weekend—even though this entails sleeping in his office during the week. His life in D.C. continues to seem quite temporary.

Perhaps this is why some Idahoans pegged him as a prospective gubernatorial candidate last year. For a while, Labrador gave demure answers to queries as to whether he might run for Governor Otter’s position—but then announced last August that he wasn’t running and said he “was not thinking about running” in the first place until supporters asked him.

“He’s good in a crowd, and good one-on-one,” Popkey says. “Even those in the tiny Democratic Party in Idaho speak well of him as a civil human being.” Popkey could see Labrador running for governor or U.S. Senate—but either way, says Popkey, “I don’t see him spending an entire career in the House.”

Yet murmurs of GOP mutiny against Speaker Boehner raise interesting questions for Labrador’s future. He’s touted as a leader of the conservative resistance—and if he continues to build a following in Washington, he may receive more votes than Amash’s in an election for speaker. At the very least, he’s shown his party something of what its future might look like.

Gracy Olmstead is an associate editor of The American Conservative.

Comments