Polygraph Nation

It is being reported that the United States government will begin to use polygraph machines more extensively in an attempt to prevent leaks to the media. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper has ordered polygraphs to be administered whenever classified information is leaked, and the tests will apply to everyone who has had access to the information.

The new policy is in response to leaks last month in two stories detailing President Barack Obama’s Tuesday morning meetings with his intelligence and security chiefs to determine who might be subject to death by drone, and the exposure of the U.S. role in the development of the Stuxnet and Flame computer viruses.

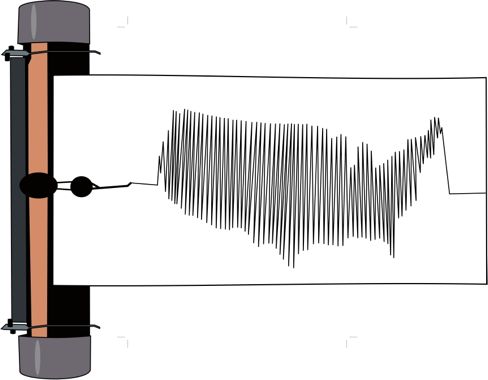

The polygraph, more commonly known as a lie detector, is an interrogation tool that has been used by law enforcement and intelligence agencies since the 1920s. It is based on the principle that people exhibit symptoms of stress when they are lying, including rapid breathing, increase in pulse rate and blood pressure, and sweating. The machine consists of a band that is strapped above the subject’s esophagus, a blood pressure cuff, and fingertip sensors to measure galvanic response.

The results are sent to a recorder that produces a chart which shows the responses to the specific questions. The FBI uses the polygraph in its investigations while both CIA and NSA use it in their hiring to determine if applicants are telling the truth when detailing their background histories. Several other U.S. intelligence agencies use the machines more selectively.

The CIA has used the polygraph extensively in vetting the veracity of its recruited agents. The exam is referred to as a “swirl” and is administered to virtually all sources that provide information that might be fabricated or contrived. Among foreign intelligence agencies, Israel’s Mossad and Military Intelligence as well as her domestic security agency Shin Beth rely on the polygraph. Most other European and Asian services employ it only when its use appears to be warranted.

It is perhaps characteristic that the United States would engage most heavily in developing machines that can tell whether someone is lying or not. The CIA and FBI have also been working with voice-stress analysis that they believe promises to become the next generation polygraph.

A polygraph test is not generally admissible in court because it does not really indicate guilt or innocence, only whether someone is reacting to the machine or to the questions being asked.

Skilled polygraph examiners conduct pre- and post-exam interviews based on a subject’s profile and the test results and, if there appears to be a serious issue, they hope to obtain a confession. During my time at CIA, one job applicant actually confessed to murder after a polygraph exam.

The common-sense approach to controlling leaks would be to carefully restrict the ability to obtain truly sensitive intelligence, but in a government where information equals access and status, that is difficult to do.

The president’s Tuesday morning meeting to draw up death lists reportedly involves as many as 100 participants both live in the White House conference room and by satellite or phone. Take each of those participants and include his or her senior staff that would be privy to the information and the number involved approaches 1000 who might have leaked the story.

Will they all be investigated or polygraphed?

It might also help if the administration were not embarking on so many questionable policies that it is trying to conceal, but that is a tale to be explored another day.

Then there is the government authorized leak. Will anyone seriously attempt to identify the leaker? In intelligence circles, most believe that the recent leaks that are now apparently being investigated by two U.S. attorneys were deliberate, designed to demonstrate that the White House is tough about ensuring America’s security and aggressive in dealing with Iran. If that is the case, Attorney General Eric Holder will make sure that the investigation goes nowhere.

The problem with using the polygraph to determine guilt or innocence is that it frequently does not work very well and once someone has demonstrated “no deception” on an exam he is certified as clean, which might well not be the case.

False results can actually provide cover for spies and criminals. Aldrich Ames, the CIA officer recruited by the Soviets, passed three lie detector tests without any indication of lying and was thereby allowed to continue to have access to top secret information in spite of other indications that there was something wrong with him. There is even a website that teaches how to defeat the exam (antipolygraph.org).

Some people are extraordinarily good liars who can beat the test consistently while others have used drugs or alcohol to deaden their physical responses. In CIA it was well known that certain national groups were difficult to polygraph. Some ethnic groups, including Arabs, were particularly hard to examine due to an ability to separate, in their own minds, lying to the examiner from any real personal dishonesty. Catholics frequently react to questions dealing with sex even if they are not lying.

The Soviet spy service successfully trained their double agents to beat the exam by making themselves physically uncomfortable during exams, sometimes inserting a pebble in a shoe and pressing hard on it to cause pain, so all the responses would show some stress. Another trick was focusing on something external, like a lamp shade in the corner of the room or a wart on the end of the examiner’s nose.

The Soviet spy service successfully trained their double agents to beat the exam by making themselves physically uncomfortable during exams, sometimes inserting a pebble in a shoe and pressing hard on it to cause pain, so all the responses would show some stress. Another trick was focusing on something external, like a lamp shade in the corner of the room or a wart on the end of the examiner’s nose.

Soviet handlers instructed Ames to have a good night’s sleep and go to the exam so relaxed that it would be possible to avoid reacting to anything. In the 1980s, the entire CIA stable of 19 Cuban agents turned out to consist of double agents, all of whom had beaten the poly, some more than once, by concentrating on their inner machismo. Lying to the Yankee examiner was the manly thing to do.

Turning the whole question of what to do to protect genuine secrets that are truly in the national interest on its head, it might be useful to ask why so many technologically advanced nations do not use the lie-detector machine. There is, of course, the question surrounding its reliability, but most intelligence and police services recognize traditional investigative and interrogation methods actually produce superior results.

In the United States there is the tendency to seek a quick fix for a problem, and if an impartial machine can somehow be inserted in the process, so much the better. It is a replay of the argument for and against enhanced interrogation, which was intended to produce intelligence of some kind fast and in production-line fashion even if the results were usually bad.

Unfortunately, once it is accepted by the public that a machine can separate truth from falsehood and can do so “legally,” it will be the new yardstick for interaction between government and the governed in a republic that is increasingly taking on the attributes of a police state.

Far better to nip the tendency in the bud now by recognizing that a machine cannot guarantee either guilt or innocence and should instead be shipped off to some government warehouse to be placed on a shelf and forgotten.

Philip Giraldi, a former CIA officer, is executive director of the Council for the National Interest.

Comments