Jacob Lawrence’s Existential Sociology

Jacob Lawrence was a pioneer. His “Migration” series, painted when he was 23, was the first work by a black American artist to be purchased by the Museum of Modern Art; his career stretched from the Harlem Renaissance into 2001, the year after his death, when his mosaic “New York in Transit” was installed in the Times Square subway.

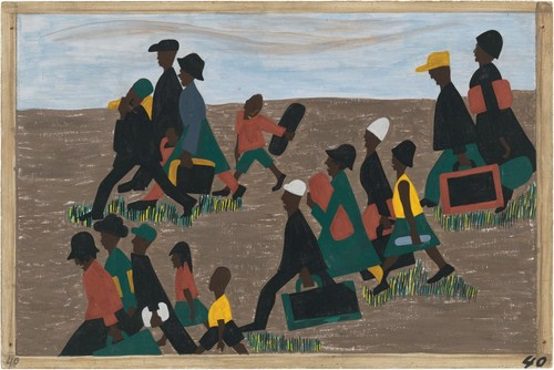

Lawrence’s style is blocky, almost cartoonish, with clear lines and contrasting colors, often in jewel tones. He took black history as his subject matter, creating series dedicated to Toussaint L’Ouverture and American abolitionists, as well as the “Migration” series, which depicted the 20th century’s great movement of six million black Southerners to the North. MoMA has done us a great service by reuniting “Migration,” which has spent decades divided between that museum and Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection.

“One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works” (on view through September 7, so plan to go soon) works hard—maybe even too hard—to put Lawrence in his cultural and historical context. The show opens with a timeline showing everything from boll weevil infestations to the formation of the Works Progress Administration. The main room reunites Lawrence’s monumental “Migration,” and is surrounded by rooms of related work by Harlem Renaissance artists and their contemporaries: paintings by Romare Bearden, poetry from Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes, video of Marian Anderson singing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The wall captions even emphasize that Lawrence researched his paintings in the library as well as talking to elders in the community.

Historical context always has its value, and the works by other artists are often striking in themselves (Bearden contributes a powerful and tender “Visitation,” and the photography section of the show is genuinely excellent, turning reportage into portraiture) and show the artists’ influence on one another: you can see Lawrence in Bearden’s 1941 painting “After Church,” with its clean lines and rich colors. And Lawrence’s non-“Migration” works show how early he developed his unmistakable color sense, his talent for composition, and the clarity of his moral vision. The timeline gives dates for events Lawrence depicts in “Migration” and, I suppose, lends his work the museum’s authority and mantle of objectivity, for those who might need that reassurance.

It’s easy to read artists—and maybe especially black artists—as mere reporters. Or, worse, sociologists. And Jacob Lawrence’s work does indeed have many reportorial or sociological characteristics: He’s racially conscious (and self-conscious about his role as a voice of his race), he’s influenced by folk art, he’s panoramic in his attempt to depict many layers of society. He has what The Wire would call “the Dickensian element.” These are all artistic choices he made that add to the power of “Migration.” To see it all in one room, all 60 stark yet brightly-colored panels, is to feel the sweep of history.

But what stood out most when I saw the whole series was Lawrence’s modern, existentialist sensibility: his sensitivity to modern loneliness. The great artistic tension in his work is the alternation between crowds and isolation. There is room for individuality in some of “Migration”‘s crowds. In panel 6, showing a railway car crammed with migrants, a mother nurses her infant and a man prays by a woman’s bunk. “Migration” is modern in its depiction of technology, the trains, and the machines—panel 7 uses rushing colored lines, flaming and flowing, as abstract images of urban life and industrial work—but it returns insistently to the inner human experience.

One of the more unusual themes in “Migration” is the presence of modern loneliness and alienation in rural scenes as well as urban ones. We’re used to bleak and inhuman depictions of skyscrapers and subway lines. But Lawrence gives us, in panel 8, Biblically-stark and leafless branches rising up from a flooded field—nature’s metonymy for the loneliness of bereft human beings. In panel 9 the delicate flowers of the cotton are attacked by giant boll weevils, against a jagged stylized background. The Southern trees are always spindly and contorted.

Panel 10, with its blunt caption “They were very poor,” shows two people alone in a room. One pot hangs on a nail. Their faces are grim and silent, and it seems like they must have been silent for a very long time.

Lawrence can be overly cartoonish, especially when he makes himself draw faces, but many of the panels here are devastating in their simplicity. Panel 15 shows lynching, not by depicting the graphic violence but by showing a figure hunched in misery under the black noose. The fear and horror radiate off the painting. The next panel is even more expressive. It’s still about lynch law, and there is still no actual depiction of a lynching. There’s just a room, with all its angles skewed and opposed to show the overturning of the intelligible and bearable world. There’s a woman seated at a table. The crazed angles show the psychological effect of lynch law, the way human cruelty can distort the way we perceive the physical world. If reporting dissects the causes of human misery, art can show how it feels; “Migration” offers both.

And “Migration” shows what longing feels like. Sometimes it’s tender longing: Panel 33 has those strange angles again—Lawrence had a phenomenal sense not only for color but for shape. A woman’s hair spreads out across her pillow as she reads a letter from a migrant relative. Golden stripes of light pour into the room. Other times there’s a harder portrayal of what it looks like to be far from those you love. Panel 46, set in a labor camp, shows no people at all; and yet the yolk-gold moon shining through the tiny far-off window could not be a more human and haunting image. The beauty of the turquoise night and golden moon makes the hard conditions of the camp stand out all the more.

Lawrence wrote “Migration”‘s captions himself. They often sound like they come from an outdated textbook: “The female worker was also one of the last groups to leave the South,” etc etc. But even these captions get striking and unexpected illustrations. The “female worker” here is stirring, highly-stylized laundry, a scene like a quilt panel, all sharp, clear, black-stitched lines and high-contrast colors.

“One-Way Ticket” is two shows: a very good show about black American artists in the ’30s, and the truly stunning one-room show devoted solely to “Migration.” Lawrence, in that series, was able to strike a balance between the sociological work of the captions and the existential yearning of the paintings.

Eve Tushnet is a TAC contributing editor, blogs at Patheos.com, and is the author of Gay and Catholic: Accepting My Sexuality, Finding Community, Living My Faith, as well as the author of the newly released novel Amends, a satire set during the filming of a reality show about alcohol rehab.

Comments