Cops With War Toys

Alexandria, Virginia’s annual big event is its George Washington’s Birthday parade. When I lived there, I usually went. One year, as President Washington passed in his carriage, I gave him a proper 18th-century bow-and-scrape—real conservatives know how to do these things. He was so pleased he stood up in his landau, doffed his hat and bowed to me in return.

It may have been the same year this genial event got skunked. Among the marching units, all festive and gay—old meaning—came the Alexandria Police SWAT team. Accompanied by an armored vehicle, they wore military fatigues, body armor, and helmets. You could watch people physically recoil as they passed. The message their gear proclaimed was “threat.”

All across the country, police departments are militarizing, often with weapons and vehicles bought for the armed forces for war and now declared surplus. To the cops, the equipment is free for the asking. A story in the June 9 New York Times reported that “During the Obama administration, according to Pentagon data, police departments have received tens of thousands of machine guns; nearly 200,000 ammunition magazines; thousands of pieces of camouflage and night-vision equipment, and hundreds of silencers, armored cars and aircraft.” The equipment facilitates the militarizing of police operations. According to the Times story:

In Florida in 2010, officers in SWAT gear and with guns drawn carried out raids on barbershops that mostly led only to charges of ‘barbering without a license’…

The ubiquity of SWAT teams has changed not only the way officers look, but also the way departments view themselves. Recruiting videos feature clips of officers storming into homes with smoke grenades and firing automatic weapons.

In terms of its effect on policing, this trend is disastrous. If the state is to keep its compact with the people, which is to maintain order and safeguard persons and property in return for cooperation, it must focus on preventing crime, not responding to it. Preventing crime in turn requires information, which police obtain by talking to citizens. Citizens are comfortable talking to police who are “Officer Friendly,” the nice-guy cop on the beat whose uniform, equipment, and demeanor are unthreatening. Few people like shooting the breeze with one of Darth Vader’s storm troopers.

The Times cites a Neenah, Wisconsin councilman—William Polinow Jr., who opposed obtaining an MRAP armored vehicle for the local police department—on why the police want the gear: “When he asks about the need for the military equipment, he said the answer is always the same: It protects police officers. ‘Who’s going to be against that? You’re against the police coming home safe at night?’”

This argument has two answers. The first is that cops, like soldiers, cannot keep themselves safe at the cost of not being able to perform the mission. (The U.S. military has this problem in large measure; the imperative of “force protection” often degrades its effectiveness.) Cops’ mission is to keep us safe, if necessary at risk to themselves. That mission requires that their interactions with almost all citizens be unthreatening because otherwise their information dries up, and they cannot prevent crime.

The second answer is to point to the British bobby, who traditionally is unarmed. How can that be? Because just as he protects his neighborhoods, so they protect him. His unthreatening presence makes him part of the community, a valued member the community does not want to see harmed.

How can police departments evaluate whether an action or development will serve their mission or work against it? One answer is “the grid.”

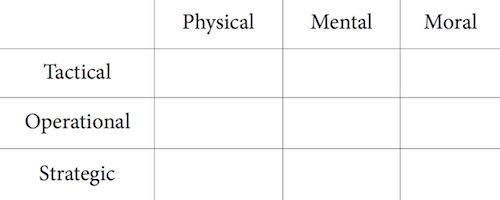

I came up with the grid while working with the Royal Marines in Plymouth, England, helping them get ready for Helmand. It combines the traditional three levels of war, visualized as rows designated “tactical,” “operational, and “strategic,” with military strategist Col. John Boyd’s three levels, depicted as columns assigned to the “physical,” “mental,” and “moral” levels.

Each of the grid’s nine boxes represents a question: how will what we are considering work—for us or against us?—with respect to these levels. A higher level trumps a lower. That means the box in the lower right corner, strategic/moral, is the most powerful, and the upper left box, tactical/physical, is the weakest.

While the grid was developed for military use, representatives of a Massachusetts police department came up to me at a conference on Boyd’s work a few years ago and said, “We now use the grid for almost all our operations.” If we put the question of militarizing the police to the grid, it tells us that militarization works well for the tactical and physical box but progressively less well for others. At the strategic and moral level—the highest—it is a disaster. Most cops, like most soldiers, love gear, and more is always better. Free gear is best of all, especially when it is big, noisy, and kind of dangerous. Unfortunately, the danger of gear that militarizes the police is to the police themselves and their ability to perform their mission. Sometimes they may need adult help to see that.

William S. Lind is author of the Maneuver Warfare Handbook and director of the American Conservative Center for Public Transportation.

Comments