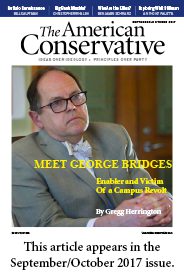

Meet the Most Embattled College President in America

George S. Bridges is, by all appearances, a pleasant fellow. With his ready smile, bow ties, and avid conviviality, the oval-faced Bridges seems to relish the role of college president—specifically, as head of The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. “My approach,’’ he once told an interviewer, “is to lead from the middle—to support the faculty and staff in their jobs and listen to their ideas and varying perspectives.’’

In practice, though, Bridges’s approach at Evergreen State this past academic year was characterized by a vast reservoir of tolerance for intolerant behavior and a willingness to turn the other cheek in the face of personal diminishment.

Whatever his actual approach to leadership, it seems to have served him well until now. His storybook career has spanned more than four decades and includes Ivy League degrees in criminology and sociology, a stint as a U.S. Justice Department official, teaching gigs at Case Western Reserve and the University of Washington, increasingly high-level responsibilities at Washington, and eventually the presidency of Whitman College, a highly regarded liberal arts institution in Walla Walla, Washington. After 10 years at Whitman, he took the reins at Evergreen in October 2015.

Throughout these years Bridges, who turns 67 on September 16, received his share of recognition, including six awards for teaching excellence at Washington, numerous academic board positions, nearly 20 research grants from prestigious national organizations, and a stint as deputy editor of a publication called Criminology, described in Bridges’s official biography as “the leading journal in his area of specialization.”

And yet in just a few weeks this spring, Bridges emerged as an academic failure. He didn’t fail in any small way but spectacularly, with the college’s reputation in shambles and the entire nation looking on. Under a banner of fighting racism, student demonstrators, often encouraged by a strident minority of faculty and staff, disrupted numerous events, patrolled the grounds menacingly with baseball bats, and reduced the president to a kind of inconsequential figure in his own office overrun by protesters. When the school year ended, mercifully, the graduation ceremony was moved for security reasons from the campus to a baseball stadium 37 miles away in Tacoma at a cost of $100,000.

During the same ugly period, an Evergreen State professor was told by the campus police chief that he should stay off campus because his safety there couldn’t be guaranteed. That professor and his faculty-member wife intend to sue the college for $3.85 million. The college now is under attack from both the right and the left—from the right for deprecating speech and activity disagreeable to the left-tilting campus; and from the left for being perceived as too lethargic in ensuring success by minority students.

In late May several dozen protesters, part of a much larger crowd that had rallied on campus, marched upstairs to Bridges’s office chanting, “Hey-hey, ho-ho, these racist teachers have got to go.” Joined by some faculty and staff, the protesters corralled the submissive Bridges and other administrators in a four-to-five-hour siege, spewing obscenities and pressing demands for more minority students, faculty, and staff, and for assurances of success at college and in life. They peppered the president with aggressive questions and, when he sought to answer, cut him off with obscenities. Example:

“No, fuck you, George. We don’t want to hear a goddamn thing you have to say….You talk so fucking much….No, you shut the fuck up.’’

And, as they say on the 11 o’clock news, much of it was “caught on camera.”

Throughout the ordeal—or what most people would consider an ordeal—Bridges demonstrated that no level of outrageous behavior on the part of these particular students could outrage him—or even outwardly faze him in any way. When the protesters expressed concerns about being docked in class for missing lectures due to their more pressing protest duties, he agreed to email faculty suggesting they cut the students some slack for any missed assignments. He sent out for pizza so they could continue to insult him on full stomachs.

But when Bridges inquired of his captors whether he might excuse himself momentarily to the men’s room, he was told bluntly to “hold it’’—then, according to one account, was accompanied to the men’s room by two protesting students to ensure he didn’t slip out the back door.

Bridges, who declined to be interviewed for this story, might accurately describe himself as empathetic—a good listener striving to correct perceived wrongs and level the playing field for minority and marginalized students. But his approach, on view to the nation via mainstream and social media as well as the op-ed pages of the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and others, suggests a fitting word to describe his leadership during a year of campus turmoil might be “hapless”—or perhaps “pathetic.”

While Bridges has been visibly occupied with student, faculty, and staff protesters and a powerful campus ethnic-identity political milieu, he has to be looking over his shoulder at a different peril: an increasingly ominous enrollment picture that he inherited. Evergreen had 4,089 students at the start of the 2016-17 academic year, down from 4,190 the year Bridges started at Evergreen and well below the 4,891 in 2009.

Evergreen State, a public institution created by the state legislature and Governor Dan Evans 50 years ago, is an innovative place, where students enroll in broad-spectrum programs rather than specific, narrowly focused classes, and they work with some of the same faculty members all four years. At term’s end, they get written assessments rather than letter grades. Student-faculty ratios are lower than at traditional colleges. The college mascot is the non-threatening geoduck clam, while its motto is “Omnia extares”—“Let it all hang out.”

A former longtime Washington secretary of state, Sam Reed, notes that the school eschews “standard [academic] fare with tight schedules and classes meeting several times a week.’’ He adds that it takes a “more or less self-directed student’’ to thrive in such an atmosphere. It’s also an atmosphere, he adds, that attracts students who are “far to the left’’ on the political spectrum.

In the wake of this year’s campus upheaval, Matt Manweller, a Republican state representative from conservative eastern Washington, said, “I can’t imagine a lot of parents are eager to have their kids attend” Evergreen State. He introduced a bill aimed at privatizing the 50-year-old college. The bill went nowhere, but Manweller called it “a figurative shot across the bow” of the Bridges administration.

Imagine, if you will, high school seniors and their parents sitting down around kitchen tables to weigh the pros and cons of possible colleges: cost, academic strengths, distance from home, football team—and campus turmoil. Among the outraged parents writing to Bridges after the May siege in his office was a mother from Illinois who said: “Because you have caved to the idiotic demands of your liberal crazed snowflake students, my husband and I have decided that Evergreen State is definitely not where we want our twins educated.”

Other factors no doubt have contributed to Evergreen’s enrollment decline, including concerns about what kind of career opportunities are fostered by the school’s emphasis on liberal arts at a time of increasing national focus on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). Dana Selby, a high-school career guidance counselor in Vancouver, Washington, thinks Evergreen’s enrollment is determined more by the economy and changing career opportunities than angst about the campus sociopolitical climate.

But Evergreen State’s campus identity now is stamped indelibly by the events of the past spring. And Bridges presents an intriguing case study at a time when the campus-protest movement across the nation has been expanding. In the 2016-17 academic year, several colleges and universities experienced high-profile assaults on free speech. Appearances by guest speakers too far to the right for the comfort of hands-over-their-ears activists were disrupted or cancelled at, among others, Vermont’s Middlebury College, the University of Washington, the University of California at Berkeley, Claremont McKenna in California, and Rutgers University in New Jersey. A riot erupted at Berkeley over the arrival of an unacceptable speaker, and physical violence at Middlebury left a teacher injured.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), which tracks free-speech issues on campuses, concluded in June 2016, “One worrisome trend undermining open discourse in the academy is the increased push by some students and faculty to ‘disinvite’ speakers with whom they disagree from campus appearances. … disinvitations have been steadily increasing over the past 15 years.”

As for the George Bridges case study, the question is what combination of traits, attributes, attitudes, and prejudices rendered him incapable of fulfilling the most important imperative of any college president: to maintain a campus culture and atmosphere conducive to the dispassionate pursuit of learning.

An assessment of Evergreen’s rolling, year-long rebellion, and Bridges’s role in it, reveals that many of the causes of his failure were self-induced and that they run deep in his political and philosophical consciousness. From the time of his arrival, he demonstrated sympathy for the causes espoused by minority students obsessed by feelings of being surrounded by racism, and he conveyed through word and deed that he would tolerate—if not welcome—the forceful expression of their grievances.

But there was another face of discord at Evergreen, this one involving faculty and staff. For those such as Professor Bret Weinstein, who have made known their views even when they are contrary to the prevailing campus orthodoxy, there is a social price to pay. That’s because Bridges, despite his boast about “leading from the middle,” hasn’t demonstrated much empathy for such “varying perspectives.’’

Indeed, Bridges’s Evergreen State tenure is most notable for his efforts to nudge and steer the entire campus toward one overarching philosophical framework, with those who resisted considered anathema by the prevailing culture. This project took a leap forward when Bridges reconstituted two committees into a new 28-member Equity and Inclusion Council, charged with recommending changes in faculty hiring practices and curriculum structures. That maneuver last fall made possible—if not inevitable—the campus disruption and ultimate humiliation of George Bridges. That’s the view, anyway, of Michael Zimmerman, provost and vice president for academic affairs until demoted by Bridges last fall. He subsequently left the college and then produced a tell-all piece this summer in the left-leaning Huffington Post.

Zimmerman objects to the way the new strategic plan of the Equity and Inclusion Council was brought forth. It was presented to the campus community as a fait accompli, he wrote, “without any public input…[and with] no opportunity for open discussion.” Rather the plan was presented as having already received Bridges’s blessing. It was unveiled at a November 16, 2016, campus-wide gathering dubbed a “Canoe Meeting”—structured, says Zimmerman, “as an opportunity to celebrate the plan’s creation.” As Zimmerman explains, “The meeting concluded with attendees being asked to metaphorically climb into a canoe to embark on a journey to equity. The implication was that if people failed to board the canoe they would be left behind.” Moreover, Zimmerman wrote, “The sentiment was expressed by some that if you were unwilling to get on board, perhaps Evergreen was not the place you should be working.”

As for Professor Weinstein, a relentless but respectful dissident against the campus zeitgeist, he wasn’t about to clamber aboard that canoe. He objected particularly to the plan’s call for “an equity justification/explanation for each potential hire/position.” This provision, Weinstein told an interviewer, “subordinates all other characteristics of applicants” to considerations of diversity, placing those above whether “the person in the front of the room knows something about the subject and has insight into teaching.”

Weinstein, according to Zimmerman, also objected to the lack of input in the proposal’s emergence. He called for “open discussion of the ideas, strategies and directions outlined in the plan,” as Zimmerman puts it. He adds, “He did so carefully and politely, never once criticizing any individual.”

On November 1, 2016, Weinstein emailed faculty members saying, “I do not believe this proposal will function to the net benefit of Evergreen’s students of color, in the present or in the future. Whatever type of vehicle it is, I hope we can find a way to discuss this proposal on its merits, before it moves farther down the line.” Then he added, “I am concerned that we are becoming a college where such things can neither be said, nor heard….I hope we will also find a way to discuss that.”

Weinstein’s lonely lament put him on the road to perdition in the view of those faculty and staff members already invested in the plan. Weinstein eventually concluded that, as he put it, “This is not a canoe. It’s an unstoppable train.”

The unstoppable train soon bore the message that Weinstein was “a racist and an obstructionist.” As Zimmerman explains in his Huffington Post article, “Evergreen isn’t very accepting of voices that question the Evergreen orthodoxy.” Thus, he adds, many faculty members, if not a majority, simply greet campus controversies with “self-censorship” in order to avoid being attacked as reprehensible human beings. Weinstein is Exhibit A in demonstrating why speaking up usually isn’t worth it.

But if Weinstein’s relations with many faculty members were edgy, they were downright toxic with Film Department professor Naima Lowe. According to Zimmerman, she called Weinstein a racist in two separate faculty meetings. “Neither the president nor the interim provost interceded to make it clear that leveling such charges against a fellow faculty member was unacceptable within the college community,” Zimmerman wrote. Nor did either administrator take any public action in response.

Indeed, there’s little dispute that the Evergreen State culture is decidedly left-leaning—and, at least in recent years, obsessed with the politics of diversity and ethnic and gender identity. It is the George Bridges outlook that college students need to be protected and shielded from views and opinions that might bruise their sensibilities—in other words, conservative views, however mildly presented.

Just how earnest that conviction is became clear in his response to a widely noted 2016 letter from the University of Chicago to its incoming freshmen. The university warned students that its commitment to free speech and open inquiry precluded its acceptance of widely used campus enforcement tools of political correctness, such as “safe spaces’’ and “trigger warnings’’ to facilitate students wishing to avoid classes and speeches that might dredge up bad memories.

Bridges would have none of it, as he emphasized in an op-ed article in the Seattle Times. He wrote that trigger warnings protected students from “genuinely distressing content that could otherwise cripple their learning.” And protective safe spaces are “critical to their success.” Then he asked rhetorically if this meant university officials were succumbing to pressures of political correctness. His answer, not surprisingly, was: “No. We are responding to the unique needs of many of our students solely for the purpose of increasing their academic and personal success.”

If Bridges’s Seattle Times piece didn’t sufficiently reveal his willingness to bend the norms of polite behavior and civil discourse to appease those who consider themselves aggrieved, his reaction to the first disruption of the year did. At a welcome convocation in September 2016, the guest speaker, scientist-author Naomi Oreskes, had finished speaking and was about to take questions when two Black Lives Matter protesters interrupted the proceedings. They stood in front of the hall with cardboard signs that read, “Evergreen cashes diversity checks, but doesn’t care about blacks.” Bridges rather deftly defused the situation, thanking the interrupters for voicing their concerns and inviting them to remain after the Q&A to discuss their issues with audience members.

But Bridges just couldn’t leave it at that. The next day he issued an all-campus email apologizing for not having scrapped the Q&A—which would have been an action of disrespect to Oreskes—and allowing the protesters to take over the event on the spot. “I believe we should have ended the ceremony once Dr. Oreskes had finished and turned our collective attention immediately to our students,” he wrote.

After that, Evergreen’s dissident students had no trouble finding forums to disrupt, often with Bridges watching quietly from the sidelines. The day after the 2016 presidential election, student agitators forced a premature end to a Board of Trustees meeting, although the official Board minutes made it sound like just another day at the office:

A large group of students joined the meeting and Ms. Sorensen (Trustees Chair Gretchen Sorensen) invited public comment. The Trustees heard comments from 48 students. Among the themes expressed were concerns over campus safety, policing, the need for more diversity among faculty and campus leadership, the need for more training for faculty on diversity, and responses to the national presidential election. President Bridges offered to continue the discussion later that afternoon. The meeting adjourned at 2:00 p.m.

It seems intuitive that the college president’s passivity in the face of each disruption would signal the “all clear” for more egregious behavior. In any event, interruptions soon ramped up in frequency and intensity.

Besides diversity and equity issues, the size of the campus police force also generated emotion among a small number of students, operating with some faculty encouragement. A lowlight of that campaign occurred January 11 at the scheduled swearing-in of Stacy Brown, the new chief of the small campus police force, herself an Evergreen alumna.

According to the student newspaper, the Cooper Point Journal, as the program was about to begin, students wrested the microphone from Wendy Endress, vice president for student affairs, and used it, “along with air horn-like noisemakers, [to yell] ‘Fuck the Police!’ and ‘Death to Pigs’.” Initially, Bridges looked on benignly, but as the disruption continued he, Brown, and other so-called authority figures simply left, and the reception ended before it started. Endress told the newspaper the protesters later “took all the donated food from the campus pantry in Police Services and defaced a vehicle.”

Fast forward to mid-March, when Professor Weinstein openly challenged plans to change the traditional “Day of Absence” (DOA) at Evergreen. In the past, students, faculty, and staff members of color were encouraged to stay off campus for a day as a way of illustrating their numbers and importance to the college.

This year, though, those in charge of the event concluded that wasn’t dramatic enough to highlight their plight. Instead of leaving campus, they felt it was the whites who should absent the college grounds for the day. “There was little or no airing of the idea to change the DOA format,” said one former faculty member who maintains campus connections. “They didn’t attempt to find out how it would be viewed by people who haven’t drunk the Kool-Aid they drink. The culture at Evergreen is to go along with such things. To look askance…would be a big strike against a faculty member.”

But Weinstein didn’t bury his concerns. In an email to Rashida Love, the staff member in charge of the DOA, and with copies to the faculty, he wrote, “There is a huge difference between a group or coalition deciding to voluntarily absent themselves from a shared space in order to highlight their vital and under-appreciated roles, and a group or coalition encouraging another group to go away. The first is a forceful call to consciousness, which is, of course, crippling to the logic of oppression. The second is a show of force, and an act of oppression in and of itself….I will be on campus on (April 12) the Day of Absence.”

And then, in the course of two days in late May, Bridges’s tolerance for intolerance reached a new level. With Weinstein’s objections to the new DOA format still gnawing at its boosters, the professor’s class was interrupted on the morning of May 23 by 50 protesters labeling him a “racist” and calling for his suspension. When Weinstein, a self-described political progressive who favored Bernie Sanders for president, tried to respond to the protesters, he was shouted down. The vitriol escalated when police arrived and protesters tried to block them from escorting Weinstein out of the building. The next day, for the sake of his and his students’ safety, he took the campus police chief’s advice and held class off campus.

Weinstein’s wife, Heather Heying, also a faculty member, responded to an email from new provost Ken Tabbutt claiming all was safe on campus. She disagreed and wrote, “Why are you putting us at risk? Why are you obscuring the facts?”

That set off Professor Lowe, whose previous labelling of Weinstein as a “racist” in a faculty meeting had stirred no rebuke from Bridges. She said on her Facebook page, “Oh lord, Could some white women at Evergreen come and collect Heather Heying’s racist ass. Jesus.” Lowe, who seems continually angry, also is featured in an expletive-rich video outside the building housing Bridges’s office. In that episode, Lowe shouts at other faculty and staff members, “YOU are the motherfuckers that we’re pushing against! You can’t see your way outta your own ass! So don’t TALK to me about what YOU need.”

At the next day’s siege of the president’s office (described above), doors were blocked and office workers and administrators became virtual hostages. Bridges has said he didn’t feel his personal safety or that of other Evergreen employees was threatened during the unruly, obscenity-laced protest in his office so he instructed campus police to stand down. “If law enforcement came in,” he said, “I feared possible escalation and damage. I made a strategic decision to de-escalate the conflict.” By the end of the day, he boasted, “we had a working plan to review the issues the students were raising. Most importantly, our students, staff, faculty and law enforcement remained safe.”

But there was collateral damage. A faculty meeting at which retirees were being honored was brought to a halt when protesters disrupted the proceedings and recruited faculty members to join them at the protest meeting in Bridges’s office suite.

Two days later, Bridges reported on the steps his administration will take in response to the demands. But, Bridges being Bridges, he included in his report some post-hostility enabling of hostilities. He expressed gratitude toward “the courageous students who have voiced their concerns” about discrimination on campus. For good measure, he threw in a little self-flagellation at having let down the students who had humiliated him: “Our results have fallen short. We should have done more to engage students in our work on equity and inclusion. We share your goals and together we can reach them.”

A few weeks later, when the campus had settled into a summer semi-hiatus, Bridges broke his silence and talked to the Olympian newspaper’s editorial board. In reference to the hostage-like takeover of his office, Bridges said, “Blocking doors—that’s a criminal act in the state of Washington—to prevent people from entering or exiting. You can’t do that in a public building.”

It seems that now, finally, Bridges sees more campus security, not tough love, as the solution to disruption and rowdiness. But as of this writing no discipline had been meted out, although he said that six students and an unspecified number of faculty members were being reviewed for possible disciplinary action for violating the school’s code of conduct. Still Bridges couldn’t help himself. He gave student violators some wiggle room by saying, “They need to be informed (of the code of conduct) because most of the students had no clue.”

The poor dears.

Bridges also conceded that he must get right with campus police officials. “What I’ve learned over the last many weeks,” he told the Olympian, “is the college hasn’t invested adequately in law enforcement.” He acknowledged that the police services unit had been underfunded for a number of years, “and we’re going to need to change that.”

Indeed, Bridges is in fence-mending mode with campus police. In a state Senate committee hearing this summer, Chief Dave Pearsall of the Thurston County Sheriff’s Office said Bridges instructed campus police chief Brown to participate unarmed in a meeting with about 100 protesters the day before the takeover of Bridges’s office.

“Why should the president of a university tell a law enforcement official what they should be doing?” Pearsall asked. “I would never in this day and age ever suggest a law-enforcement officer go someplace unarmed.” Summoned back to the witness table to respond, Bridges acknowledged the lapse. “I made a mistake,” he said. “I was wrong, and I’ve apologized to her for it.” (In early August campus police chief Brown resigned her post after less than a year to become a police officer in nearby Tumwater, Washington.)

A few days after the siege of his classroom, Weinstein accepted an invitation to tell his side of the story to Tucker Carlson on Fox News, a network that is anathema to the Evergreen State version of political correctness. Then the media floodgates opened. Given a spot on the Wall Street Journal’s op-ed page, Weinstein wrote, “Evergreen has slipped into madness.”

The mainstream press and conservative websites, blogs, and talk shows jumped all over the story. On June 3, the liberal New York Times columnist Frank Bruni wrote, “We’re never going to make the progress [combatting racism] that we need to if [students] hurl the word ‘racist’ as reflexively and indiscriminately as some of them do, in a frenzy of righteousness aimed at gagging speakers and strangling debate….The recent ugliness at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, echoed too many other incidents at too many other schools.”

But this seems to be a saga without any near-term end. In early July, Weinstein and his wife filed their $3.85 million tort claim against the college, alleging that the college subjected them to what their lawyer called “extraordinary events’’ and failed “to protect them as a target for their protracted activity, leaving the harassers in charge of the workplace and Professor Weinstein on the run.” The claim is the first step in what could lead to a suit and an ugly court battle.

Bridges does have defenders. One is Liza Rognas, chair of the Faculty Assembly, who says the president “has done more than was done in the previous eight to 10 years” to improve campus diversity and equity. “I see with George the first really strong concern. That’s why he listened so long” when his office was overrun by protesters.

But Rognas is named in Weinstein’s tort claim as having joined with other faculty members to complain “that a photo essay documenting campus response to the (November 2016) elections showed too many white people.” Weinstein’s tort claim describes that as just one of the “racially divisive communications sent on the faculty and all-campus email list serves.” The claim also cites a Facebook post by Professor Lowe the day after the Trump election: “To my white friends: You’re on notice. If you’re not paying me cash money, working on the impeachment plan, or burning a cop shop to the ground, we don’t have much to say to each other.”

And what of Bridges’s bosses, the Evergreen board of trustees? Board Chair Gretchen Sorensen declined to be interviewed for this story, as did Bridges and U.S. Rep. Denny Heck, a Democrat and Evergreen State alumnus whose congressional district includes the college.

On June 3, eight days after the takeover of Bridges’s office, Sorensen said in a written statement that anyone who “prevents Evergreen from delivering a positive and productive learning environment for all students has and will continue to be held accountable for their actions and face appropriate consequences.” She did not say if that included George Bridges.

Meanwhile, the drama continued into the summer. It was in response to anonymous phone threats that the campus was shut down for three days at term’s end and the June 16 graduation ceremony was moved to a more secure Tacoma baseball stadium—at the aforementioned price tag of $100,000, demonstrating the cost of disruption to institutions that abet it. During that period a few students, having heard rumors that right-wing thugs were coming to make trouble, armed themselves with baseball bats and did vigilante patrols on campus until college officials implored them to return to their dorms. In early July, police arrested a 53-year-old Morris Plains, N.J., man in connection with the phone threats.

At the Tacoma commencement, meanwhile, board of trustees Chair Sorensen made just one reference to the tumultuous school year that had just ended: “We are living in a politically and emotionally charged time and the events of the past few weeks here can and should become a teachable moment for all of us,’’ she said blandly. “Going forward, we clearly have work to do. But we have the right people in place to lead that work.”

Just who learned what in the teachable moment was not clear.

Gregg Herrington is a retired reporter and editor for the Associated Press in Washington D.C. and Seattle, and the Columbian newspaper in Vancouver, Wash., where he lives.

Comments